SOME OF "WILD BILL'S" RECOLLECTIONS.

The author visited him at his home in Nebraska, in the spring of 1907. The noted hunter, Indian fighter, and scout, Sol. Rees, took me from Jennings, Kansas, to the home of Kress, near Hastings, Nebr., generously defraying the expenses. The three of us separated in Texas in the spring of 1878; and after twenty-nine years of neither hearing from nor seeing each other, we held a reunion of the "Forlorn Hope;" and it did my heart good to once more meet this big, generous, warm-hearted plainsman of the old days. As I looked in the face of the man who stood as a buffer between the settlers and wild Indians on the frontier of Nebraska and the western border of Texas, my thoughts went back to two particular incidents of the many thrilling ones I had passed through in company with him.

The first was at the hunters' fight with the Indians on the 18th of March, 1877, already described. All through that fierce fight, he kept a level head and used a dangerous gun. He tore away the mask and showed the real mettle and fiber of his composition. When there would be a lull in the fight, or a change of base was made, Kress kept those within his hearing livened up by his dry humor and seemingly total indifference to his surroundings.

Then again on the 27th, 28th and 29th of July, already alluded to, he divided up a six-pound powder-can of water as generously as though a river were flowing nearby; and men of his type suffered and moved on. How thankful I felt while at his home, so beautifully located on the banks of the sparkling waters of the Little Blue, to see my comrade living in a manor-house, his cribs and granaries groaning with the 1906 harvest, and surrounded by a community that fairly pay him reverence. For they know enough of his past life and the sacrifices he made, to help make it possible for his neighbors to have the peaceful, happy homes that surround this once "Wild Bill." In the country where he resides he was the first settler on the Little Blue, having homesteaded in 1869. He has identified himself with that particular region for thirty-nine years; and has seen the passing of the overland stage line, the Indian, and the buffalo.

And he is far better equipped to write "The Border and the Buffalo," than myself. He is a native of Pennsylvania; soldiered four years during the Rebellion, in the First Pennsylvania Cavalry. I was closely identified with him from 1875 to 1878, in Texas, in a common cause, viz., "The destruction of the buffalo, and settling the wild Indian question," which had the approval of all frontier army officers, regardless of the fact that Ernest Thompson Seton said "the hunters were the dregs of the border towns."

While talking with Kress at his home in regard to his experience on the 29th and 30th of July, 1877, when we became demoralized for want of water, I learned that he and Jim Harvey, our citizen captain, were in very poor health when we left the Double Lakes on the 27th. Here is his own statement:

"I dissent from your version of Captain Nolan setting his compass for the Double Lakes. That is what he talked of; but he tried to go northeast. I had quite a talk with Lieutenant Cooper that morning. Their bugler had been across there the summer before. There were four wagons in the outfit; and that bugler convinced Cooper and Nolan that he could strike the trail and follow it to the Casa Amarilla, Yellow House Springs. I told the lieutenant it would be impossible, as the new grass had grown since then and the best of trailers would fail to find it. But they started north of northeast, while the lieutenant and I stood talking. I soon drew his attention to the bugler circling to the east, and remarked that 'he could not follow any course; that his officers should pay no attention to him, but strike a course of their own.' And I added: 'As for me, I am going northeast.' While we were yet talking, the command was going due east. The lieutenant remarked that they were 'like a lot of sheep without a leader or herder.' During this time my horse started off toward the troops, and I walked four miles before I overtook him. Benson caught him for me, as he had left you boys and gone to the soldiers. By this time the soldiers were going southeast. I tried to get Benson to go with me toward the Casa Amarilla, but he said he was going east. Poor fellow! He had a worse time than any of us.

"I started back, cutting off the angle. When I met Jim Harvey, about four miles from where I left Benson, he told me that Perry and George Williams were back near the place where we dry-camped the night before, and he could not get them to walk. He asked me to go back with him and we would try to get them through in the evening. So back we went. I led my horse. Harvey, Perry, and George had each lost his horse during the night. We made a shade for the boys by digging holes in the ground with our butcher-knives, setting the stock of each big-fifty in the holes, then guying the muzzles with my lariat. We then put blankets on top and had a good shade for them. I think it was now near noon, and very hot.

"After a while George thought he could travel. So he and Harvey started on. I tried to get Perry on my horse, but he was too much played out to try to help himself. Great beads of cold sweat dropped from my brow while I was trying to lift him onto my horse. After Harvey and George had gone about a mile, George toppled over. Harvey went on, and met two negro soldiers, who were returning from the Laguna Plata with water. They gave Harvey one full canteen, rode on, and gave George one; then came onto Perry and me. The soldiers, who had several canteens, divided with us.

"About 3 P. M. we were all four together, the soldiers having passed on seeking their command. As the shades of night came on, we dropped to sleep. But it was a troubled one. Thirst ever haunted us. It was _thirst_, water, thirst and water, until it was all gone, and still we were all in a horrible condition. That same night along toward morning it rained some, where we were, but the rain was heavier north and east of us. We spread out the blanket and caught a few sips of water.

"At daylight I started on to look for water. I could hear a great roaring to the north, while it was sprinkling where we were. I went afoot, hoping to find a depression or lagoon containing water. I went much farther than I thought, or had intended to go, and was on the point of turning back, when I saw a lagoon with water in it about two hundred yards from me. As I started toward it I looked. While looking to the east a long way off I saw two men on horseback. I fired my big-fifty gun, and at the same time, walked backward and forward. I fired three shots before attracting their attention. I saw them stop, then start toward me. When they came up it was Dick Wilkinson and Al. Waite. They said: 'We could not hear your gun, but saw the smoke, we are truly glad to see you alive. How and where are Harvey and the other boys? You and Harvey concerned us the most, as you were both very sick men when we left the Double Lakes.'

"I told them the others were O. K. They both dismounted, and we all went down to the lagoon. They handed me a quart cup to drink from, and I drank a-plenty. The boys emptied the water out of the green antelope-hide they had been carrying all night, and refilled it with rain-water, and we started back to where the other three men were. We had not proceeded far when I said: 'Dick, ride on, and we will stay here. There is no use of us all going over the ground twice.' So on he went. Soon a shot was fired by the boys, who had become uneasy about me. Dick heard it, and had no trouble in riding to them.

"When they got back to the lagoon and had quenched their thirst, it commenced to rain, and there was quite a shower. Perry began grumbling about getting so wet. This exasperated me so much that, weak as I was, I threw him into the lagoon. We made some coffee here, and ate some bread and antelope-meat which the relief boys had brought out. Then we started on. I told Perry to ride my horse, and Jim Harvey and I walked along together. As darkness was approaching we were nearing the Casa Amarilla, when Perry, who was always in the rear, dismounted, and my horse wandered away from him, and I never heard of him or the saddle again. But Perry did get to camp. Now, Cook, you know the rest."

* * * * *

Yes, the author feels that he knows something of the entire proceedings of the ninety days we were in that sun-baked region. And I then felt I was in the company of a brave man.

Reader, he is today a living example of human fortitude. Chivalrous, charitable, jovial, kind and considerate. He was geography itself, having roamed over the country from the Big Horn to southern Texas, and from the Missouri River to the Rocky Mountains.

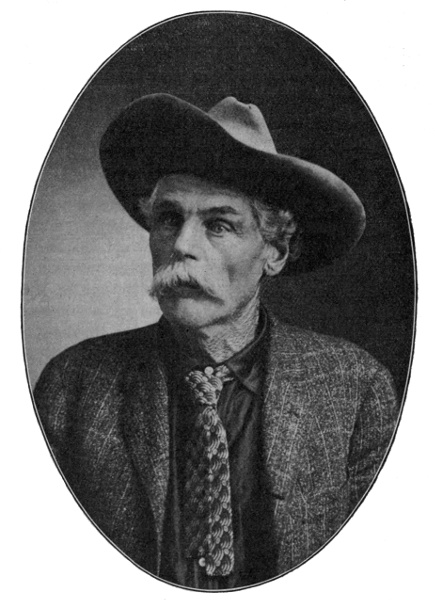

The American Desert, as it was marked on the old maps, faded away and became the homes of multiplied thousands under his personal observation. Perhaps no man has seen a greater advance of civilization, in the same length of time, than this old plainsman, whose picture, together with his daughter Alene, will be found in this chapter.

BILL KRESS'S YEARNINGS FOR THE BUFFALO RANGE.

1. It comes to me often in silence, When the firelight glimmers low, And the black, uncertain shadows Seem wraiths of long ago. Always with a throb of heart-ache, That thrills each pulsive vein, Comes that old, unquiet longing, For the "Buffalo Range" again.

2. I am sick of the din of cities, And the faces cold and strange, I feel the warmth and welcome Where my yearning fancies range Back to the old border homestead. With an aching sense of pain, I dream of that old chasing On the Buffalo Range again.

3. Far out in the distant shadows Is the buffalo crash and din, And, slowly the cloudy shadows Come drifting, drifting in; Sobbing the night-wind murmurs To the splash of the Texas rain; Come back to me the memories Of the Buffalo Hunt again.

4. To me those memories, "thus Muse," That never may die away. It seems the hands of angels, On a mystic harp at play, Have touched with a yearning sadness On a beautiful, broken strain, To which is my fond heart yearning For the Buffalo Chase again.