Following the discovery of gold in California in January 1848, that region sprang into immediate prominence. From all parts of the country and the remote corners of the earth came the famous Forty-niners.

Amid the chaos of a great mining camp the Anglo-Saxon love of law and order soon asserted itself. Civil and religious institutions quickly arose, and, in the summer of 1850, a little more than a year after the big rush had started, California entered the Union as a free state.

The boom went on and the census of 1860 revealed a population of 380,000 in the new commonwealth. And when to these figures were added those of Oregon and Washington Territory, an aggregate of 444,000 citizens of the United States were found to be living on the Pacific Slope. Crossing the Sierras eastward and into the Great Basin, 47,000 more were located in the Territories of Nevada and Utah,--thus making a grand total of nearly a half million people beyond the Rocky Mountains in 1860. And these figures did not include Indians nor Chinese.

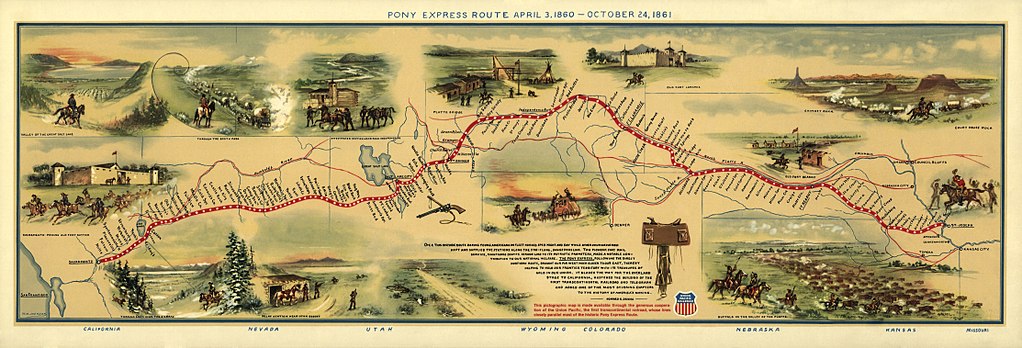

Without reference to any military phase of the problem, this detached population obviously demanded and deserved adequate mail and transportation facilities. How to secure the quickest and most dependable communication with the populous sections of the East had long been a serious proposition. Private corporations and Congress had not been wholly insensible to the needs of the West. Subsidized stage routes had for some years been in operation, and by the close of 1858 several lines were well-equipped and doing much business over the so-called Southern and Central routes. Perhaps the most common route for sending mail from the East to the Pacific Coast was by steamship from New York to Panama where it was unloaded, hurried across the Isthmus, and again shipped by water to San Francisco. All these lines of traffic were slow and tedious, a letter in any case requiring from three to four weeks to reach its destination. The need of a more rapid system of communication between the East and West at once became apparent and it was to supply this need that the Pony Express really came into existence.

The story goes that in the autumn of 1854, United States Senator William Gwin of California was making an overland trip on horseback from San Francisco to Washington, D. C. He was following the Central route via Salt Lake and South Pass, and during a portion of his journey he had for a traveling companion, Mr. B. F. Ficklin, then General Superintendent for the big freighting and stage firm of Russell, Majors, and Waddell of Leavenworth. Ficklin, it seems, was a resourceful and progressive man, and had long been engaged in the overland transportation business. He had already conceived an idea for establishing a much closer transit service between the Missouri river and the Coast, but, as is the case with many innovators, had never gained a serious hearing. He had the traffic agent's natural desire to better the existing service in the territory which his line served; and he had the ambition of a loyal employee to put into effect a plan that would bring added honor and preferment to his firm. In addition to possessing these worthy ideals, it is perhaps not unfair to state that Ficklin was personally ambitious.

Nevertheless, Ficklin confided his scheme enthusiastically to Senator Gwin, at the same time pointing out the benefits that would accrue to California should it ever be put into execution. The Senator at once saw the merits of the plan and quickly caught the contagion. Not only was he enough of a statesman to appreciate the worth of a fast mail line across the continent, but he was also a good enough politician to realize that his position with his constituents and the country at large might be greatly strengthened were he to champion the enactment of a popular measure that would encourage the building of such a line through the aid of a Federal subsidy.

So in January, 1855, Gwin introduced in the Senate a bill which proposed to establish a weekly letter express service between St. Louis and San Francisco. The express was to operate on a ten-day schedule, follow the Central Route, and was to receive a compensation not exceeding $500.00 for each round trip. This bill was referred to the Committee on Military Affairs where it was quietly tabled and "killed."

For the next five years the attention of Congress was largely taken up with the anti-slavery troubles that led to secession and war. Although the people of the West, and the Pacific Coast in particular, continued to agitate the need of a new and quick through mail service, for a long time little was done. It has been claimed that southern representatives in Congress during the decade before the war managed to prevent any legislation favorable to overland mail routes running North of the slave-holding states; and that they concentrated their strength to render government aid to the southern routes whenever possible.

At that time there were three generally recognized lines of mail traffic, of which the Panama line was by far the most important. Next came the so-called southern or "Butterfield" route which started from St. Louis and ran far to the southward, entering California from the extreme southeast corner of the state; a goodly amount of mail being sent in this direction. The Central route followed the Platte River into Wyoming and reached Sacramento via Salt Lake City, almost from a due easterly direction. On account of its location this route or trail could be easily controlled by the North in case of war. It had received very meagre support from the Government, and carried as a rule, only local mail. While the most direct route to San Francisco, it had been rendered the least important. This was not due solely to Congressional manipulation. Because of its northern latitude and the numerous high mountain ranges it traversed, this course was often blockaded with deep snows and was generally regarded as extremely difficult of access during the winter months.

While a majority of the people of California were loyal to the Union, there was a vigorous minority intensely in sympathy with the southern cause and ready to conspire for, or bring about by force of arms if necessary, the secession of their state. As the Civil War became more and more imminent, it became obvious to Union men in both East and West that the existing lines of communication were untrustworthy. Just as soon as trouble should start, the Confederacy could, and most certainly would, gain control of the southern mail routes. Once in control, she could isolate the Pacific coast for many months and thus enable her sympathizers there the more effectually to perfect their plans of secession. Or she might take advantage of these lines of travel, and, by striking swiftly and suddenly, organize and reinforce her followers in California, intimidate the Unionists, many of whom were apathetic, and by a single bold stroke snatch the prize away from her antagonist before the latter should have had time to act.

To avert this crisis some daring and original plan of communication had to be organized to keep the East and West in close contact with each other; and the Pony Express was the fulfillment of such a plan, for it made a close cooperation between the California loyalists and the Federal Government possible until after the crisis did pass. Yet, strange as it may seem, this providential enterprise was not brought into existence nor even materially aided by the Government. It was organized and operated by a private corporation after having been encouraged in its inception by a United States Senator who later turned traitor to his country.

It finally happened that in the winter of 1859-60, Mr. William Russell, senior partner of the firm of Russell, Majors, and Waddell, was called to Washington in connection with some Government freight contracts. While there he chanced to become acquainted with Senator Gwin who, having been aroused, as we have seen, several years before, by one of the firm's subordinates, at once brought before Mr. Russell the need of better mail connections over the Central route, and of the especial need of better communication should war occur.

Russell at once awoke to the situation. While a loyal citizen and fully alive to the strategic importance which the matter involved, he also believed that he saw a good business opening. Could his firm but grasp the opportunity, and demonstrate the possibility of keeping the Central route open during the winter months, and could they but lower the schedule of the Panama line, a Government contract giving them a virtual monopoly in carrying the transcontinental mail might eventually be theirs.

He at once hurried West, and at Fort Leavenworth met his partners, Messrs. Majors and Waddell, to whom he confidently submitted the new proposition. Much to Russell's chagrin, these gentlemen were not elated over the plan. While passively interested, they keenly foresaw the great cost which a year around overland fast mail service would involve. They were unable to see any chance of the enterprise paying expenses, to say nothing of profits. But Russell, with cheerful optimism, contended that while the project might temporarily be a losing venture, it would pay out in time. He asserted that the opportunity of making good with a hard undertaking--one that had been held impossible of realization--would be a strong asset to the firm's reputation. He also declared that in his conversation with Gwin he had already committed their company to the undertaking, and he did not see how they could, with honor and propriety, evade the responsibility of attempting it. Knowledge of the last mentioned fact at once enlisted the support or his partners. Probably no firm has ever surpassed in integrity that of Russell, Majors, and Waddell, famous throughout the West in the freighting and mail business before the advent of railroads in that section of the men, the verbal promise of one of their number was a binding guarantee and as sacredly respected as a bonded obligation. Finding themselves thus committed, they at once began preparations with tremendous activity. All this happened early in the year 1860.

The first step was to form a corporation, the more adequately to conduct the enterprise; and to that end the Central Overland California and Pike's Peak Express Company was organized under a charter granted by the Territory of Kansas. Besides the three original members of the firm, the incorporators included General Superintendent B. F. Ficklin, together with F. A. Bee, W. W. Finney, and John S. Jones, all tried and trustworthy stage employees who were retained on account of their wide experience in the overland traffic business. The new concern then took over the old stage line from Atchison to Salt Lake City and purchased the mail route and outfit then operating between Salt Lake City and Sacramento. The latter, which had been running a monthly round trip stage between these terminals, was known as the West End Division of the Central Route, and was called the Chorpenning line.

Besides conducting the Pony Express, the corporation aimed to continue a large passenger and freighting business, so it next absorbed the Leavenworth and Pike's Peak Express Co., which had been organized a year previously and had maintained a daily stage between Leavenworth and Denver, on the Smoky Hill River Route.

By mutual agreement, Mr. Russell assumed managerial charge of the Eastern Division of the Pony Express line which lay between St. Joseph and Salt Lake City. Ficklin was stationed at Salt Lake City, the middle point, in a similar capacity. Finney was made Western manager with headquarters at San Francisco. These men now had to revise the route to be traversed, equip it with relay or relief stations which must be provisioned for men and horses, hire dependable men as station-keepers and riders, and buy high grade horses[1] or ponies for the entire course, nearly two thousand miles in extent. Between St. Joseph and Salt Lake City, the company had its old stage route which was already well supplied with stations. West of Salt Lake the old Chorpenning route had been poorly equipped, which made it necessary to erect new stations over much of this course of more than seven hundred miles. The entire line of travel had to be altered in many places, in some instances to shorten the distance, and in others, to avoid as much as possible, wild places where Indians might easily ambush the riders.

The management was fortunate in having the assistance of expert subordinates. A. B. Miller of Leavenworth, a noteworthy employe of the original firm, was invaluable in helping to formulate the general plans of organization. At Salt Lake City, Ficklin secured the services of J. C. Brumley, resident agent of the company, whose vast knowledge of the route and the country that it covered enabled him quickly to work out a schedule, and to ascertain with remarkable accuracy the number of relay and supply stations, their best location, and also the number of horses and men needed. At Carson City, Nevada, Bolivar Roberts, local superintendent of the Western Division, hired upwards of sixty riders, cool-headed nervy men, hardened by years of life in the open. Horses were purchased throughout the West. They were the best that money could buy and ranged from tough California cayuses or mustangs to thoroughbred stock from Iowa. They were bought at an average figure of $200.00 each, a high price in those days. The men were the pick of the frontier; no more expressive description of their qualities can be given. They were hired at salaries varying from $50.00 to $150.00 per month, the riders receiving the highest pay of any below executive rank. When fully equipped, the line comprised 190 stations, about 420 horses, 400 station men and assistants and eighty riders. These are approximate figures, as they varied slightly from time to time.

Perfecting these plans and assembling this array of splendid equipment had been no easy task, yet so well had the organizers understood their business, and so persistently, yet quietly, had they worked, that they accomplished their purpose and made ready within two months after the project had been launched. The public was scarcely aware of what was going on until conspicuous advertisements announced the Pony Express. It was planned to open the line early in April.

[1] While always called the Pony Express, there were many blooded horses as well as ponies in the service. The distinction between these types of animals is of course well known to the average reader. Probably "Pony" Express "sounded better" than any other name for the service, hence the adoption of this name by the firm and the public at large. This book will use the words horse and pony indiscriminately.