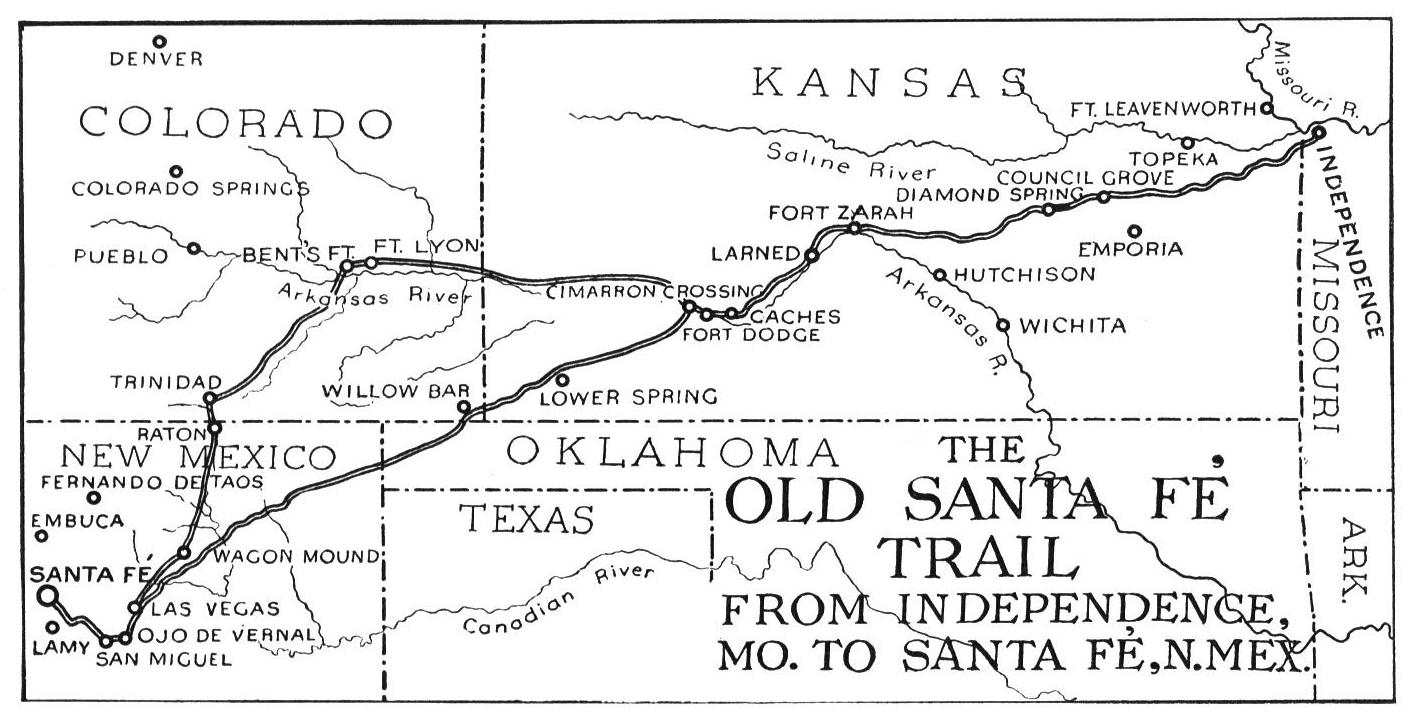

The Santa Fe Trail in days of prosperous Santa Fe trade extended from Independence, Missouri, to Santa Fe, New Mexico. It was a natural route and was old and well trod by primitive inhabitants long before the early Spanish explorers followed portions of it. The first Americans to follow it were the pioneer hunters and trappers. Pike was the first American explorer who followed it up the Arkansas river. The first successful venture to Santa Fe over the trail was made by Captain William Becknell in 1821, and this date marked the beginning of Santa Fe trade.

The upper Arkansas river route followed up the north side of the Arkansas river from the Cimarron crossing, through the counties of Gray, Finney, Kearny and Hamilton, and is today represented by the main line of the Atchison, Topeka & Santa Fe railway. It was used by those desiring to stop at Bent's Fort, in Colorado, Trinidad, Raton Pass and to Santa Fe. In Finney county there was only one place of historic importance, and that was the United States government crossing, which was made by the survey of 1825. The route recommended by the government crossed the Arkansas river to the south side and entered Mexican territory at a point about six miles up the river from Garden City, near Holcomb. The following is the original description of the crossing as given out by the government surveyors: "Crossing of the Arkansas river at the Mexican boundary of the looth degree, just below the bend of the river, at the lower end of a small island with a few trees. At this place there are no banks on either side to hinder wagons. The river is here very shallow, not more than knee deep in a low stage of the water. The bed of the river is altogether sand and is unsafe to stand long on one place with a wagon or it may sink in the sand. "The upper route is more safe for herding stock and more commodious to the traveler as he will always be sure of wood and water and a sure guide and in general it is easier to kill buffalo for provision."

From this crossing, the trail followed south of the river to Chouteau Island, near the present town of Hartland, which was a place of historic importance. It was to this point that the disastrous expedition of Chouteau (1815-1817) retreated and successfully resisted a Comanche attack. Many things marked this place so strongly that the traveler could not mistake it. It was the largest island of timber in the river and on the south side of the river at the lower end of the island was a thicket of willows. In 1829 Major Bennett Riley was ordered to take four companies of the 6th Infantry and accompany a trader caravan to the western frontier. He escorted the caravan to Chouteau Island without any molestation whatever. He camped on the north bank of the Arkansas and watched the American wagons disappear in the desert wastes of Mexican territory. They had gone but a short distance when they were attacked by Indians. Major Riley went to their assistance, although he knew the gravity of taking his troops on foreign territory. The Indians retreated, but he went one day more with the traders. He camped at Chouteau until their return and was beset by Indians all summer.

From Chouteau Island the route turned south to "Wagon Bed Spring" of the Cimarron. This was a much safer and better watered route than the one by way of Cimarron crossing.

The Cimarron crossing was a shorter, but more dangerous cut-off to Santa Fe. There was less water and fuel and the Indians were more hostile. It crossed Haskell, Grant and Morton counties to the southwest corner of the state.

During the first years the trade was largely carried on by detached parties who used pack animals to carry their merchandise. But the loss incurred from the raids of hostile Indians soon made it necessary to join for common safety, and they began moving in trains.

There was a gradual growth of the Santa Fe trade from 1821 to 1843. At the close of that period, the Santa Fe trade was brought to a sudden stop by the closing of all Mexican frontier ports of entry by a proclamation of Santa Ana. He believed the Americans were aiding and sympathizing with the Texans, who had declared their independence of Mexico.

It was not until the trouble with Mexico was settled, or until 1850, that this great overland trail again became the path of a constantly increasing tide of trade and travel. During the early years the trail which the wagons followed was strewed along with the bones of horses, oxen and men, who had died on the way from hunger, thirst and exhaustion or from attacks of Indians. But after the restrictions of the Mexican trade were removed and New Mexico and California became a part of the Union, the trade and travelers again increased in volume until caravans of emigrants and traders moved along the trail through Southwestern Kansas in almost as continuous a line as the trains of the Santa Fe railroad of today. D. W. Barton states that the famous Cimarron crossing on the Arkansas was at Ingalls, and he pointed out the exact place, just west of his home where he had seen many caravans cross the river. The old ruts made by the trampling of ox teams, the wheels of government wagons, prairie schooners and pack mules, are still visible at points on the hills, both north and south of the river at Ingalls. He says there was not much traffic on the Santa Fe trail after the Santa Fe railroad (now the BNSF) was built. The Indians were still hostile toward the caravans and he recalls how they utterly destroyed the last wagon train which attempted to cross his range in 1873.

The same general route of the old Santa Fe trail, as it crossed this region, is still used as a national highway. But, the new trail has been straightened, the ruts graded up by modern machinery, and the soil covered over with a lasting grade of cement, or gravelled. The trail of today winds like a white ribbon through fields of grain and pastures of blooded stock. Its stream of traffic is immensely greater than ever in olden times, resembling more the thoroughfare of a city than it does a country road.

Thousands of travelers pass along this famous overland avenue every year. Luxurious, high-powered passenger buses, great trucks, and vans loaded with merchandise. The sad part is that it has lost its identity and is now called U.S. Highway 50 South. There is nothing in the state of Kansas that has more historic importance than the Santa Fe trail. It is many years older than the state itself. Millions of American people would be delighted to travel over "the old national highway" if they were rightly directed. It should stand distinctly as a marked highway across the state, and spots of particular interest should be so marked by fitting monuments.

The old John Beatty ranch on the Cimarron River south of Richfield, Kansas, was the scene of a tragedy on the Santa Fe Trail in the early 50's. A man by the name of Alexander, granduncle of J. T. Alexander of Mullinville, Kansas, in company with four other men, left their homes in Illinois and followed the Santa Fe Trail from Independence, Missouri, to Santa Fe, New Mexico, with three wagons loaded with dry goods. They arrived safely and sold their calico for $2 a yard, and were paid with silver ware and silver bullion. On their return trip they got as far as the Cimarron river, where they made camp.

That night, Indians came and drove off their horses. They buried their silver, piled their wagons on top of it and burned them, and then started for their homes on foot. Their ammunition was used up before they reached Independence, Missouri, and they were in a famished condition when they reached that point. The buried bullion has never been discovered.