In the fall of 1854, United States Senator W. M. Gwin of California made the trip from San Francisco east en route to Washington, D. C., on horseback, by the way of Salt Lake City and South Pass, then known as the Central Route. For a part of the way he had for company Mr. B. F. Ficklin, the general superintendent of the freighting firm of Russell, Majors & Waddell.

Out of this traveling companionship grew the pony express. Mr. Ficklin's enthusiasm for closer communication with the East was contagious, and Senator Gwin became an untiring advocate of an express service via this route and on the lines suggested by Mr. Ficklin.

The methods of this firm can best be illustrated by the pledge they required every employee to sign, namely: "While in the employ of Russell, Majors & Waddell, I agree not to use profane language, not to get drunk, not to gamble, not to treat animals cruelly, and not to do anything incompatible with the conduct of a gentleman," etc. After the war broke out, a pledge of allegiance to the United States was also required. The company adhered, so far as possible, to the rule of not traveling on Sunday and of avoiding all unnecessary work on that day. A stanch adherence to these rules, and a strict observance of their contracts, in a few years brought them the control of the freighting business of the plains, as well as a widespread reputation for conducting it on a reliable and humane basis.

Committed to the enterprise, the firm proceeded to organize the Central Overland California and Pike's Peak Express Company, obtaining a charter under the State laws of Kansas.

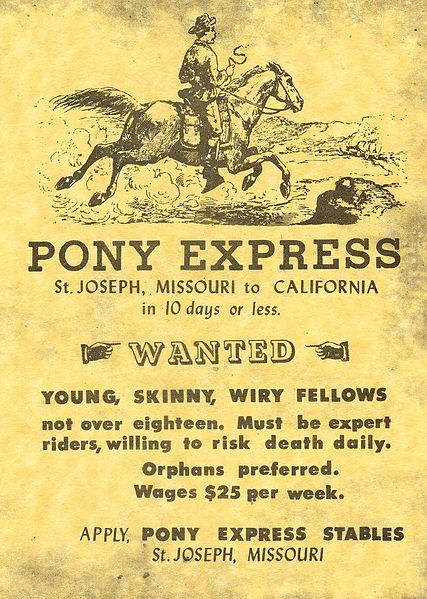

The company had an established route with the necessary stations between St. Joseph and Salt Lake City. Chorpenning's line west of Salt Lake City had few or no stations, and these had to be built; also some changes in the route were considered advisable. The service comprised sixty agile young men as riders, one hundred additional station-keepers, and four hundred and twenty strong, wiry horses. So well did those in charge understand their business that only sixty days were required to make all necessary arrangements for the start. April 3, 1860, was the date agreed upon, and on that day the first pony express left St. Joseph and San Francisco. In March, 1860, the following advertisement had appeared in the _Missouri Republican_ of St. Louis and in other papers:

To San Francisco in 8 days by the C. O. C. & P. P. Ex. Co. The first courier of the Pony Express will leave the Missouri River on Tuesday, April 3rd, at---- P. M., and will run regularly weekly hereafter, carrying a letter mail only. The point on the Mo. River will be in telegraphic connection with the east and will be announced in due time.

Telegraphic messages from all parts of the United States and Canada in connection with the point of departure will be received up to 5:00 P. M. of the day of leaving and transmitted over the Placerville & St. Jo to San Francisco and intermediate points by the connecting express in 8 days. The letter mail will be delivered in San Francisco in 10 days from the departure of the express. The express passes through Forts Kearney, Laramie, Bridger, Great Salt Lake City, Camp Floyd, Carson City, The Washoe Silver Mines, Placerville and Sacramento, and letters for Oregon, Washington Territory, British Columbia, the Pacific Mexican ports, Russian possessions, Sandwich Islands, China, Japan and India will be mailed in San Francisco.

Both Sacramento and San Francisco were afire with enthusiasm, and elaborate plans were set on foot to welcome the first express. At the former point the whole city turned out with bells, guns, bands, etc., to greet it. Making only a brief stop to deliver the mail for that point, the express was hurried abroad the swift steamer _Antelope_, and sent forward to San Francisco. Here its prospective arrival had been announced by the papers, and also from the stages of the theaters, so that an immense as well as enthusiastic crowd awaited its arrival at midnight. The California Band paraded; the fire-bells were rung, bringing out the fire companies, who, finding no fire, remained to join in the jollity and to swell the procession which escorted the express from the dock to the office of the Alta Telegraph, its Western terminus.

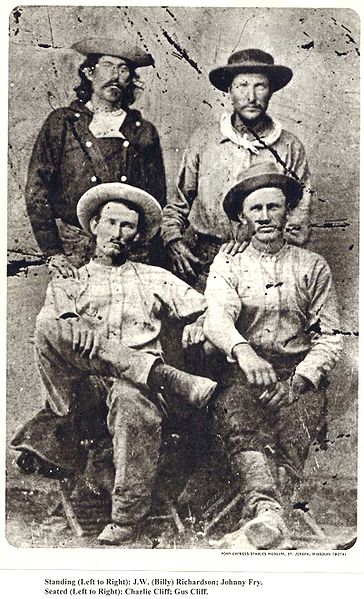

All the riders were young men selected for their nerve, light weight, and general fitness. No effort was made to uniform them, and they dressed as their individual fancy dictated, the usual costume being a buckskin hunting-shirt, cloth trousers tucked into a pair of high boots, and a jockey-cap or slouch-hat. All rode armed. At first a Spencer rifle was carried strapped across the back, in addition to a pair of army (Colt's) revolvers in their holsters. The rifle, however, was found useless, and was abandoned. The equipment of the horses was a light riding-saddle and bridle, with the saddle-bags, or _mochila_, of heavy leather. These had holes cut in them so that they would fit over the horn and tree of the saddle. The mochilas had four pockets, called _cantinas_, one in each corner, so as to have one in front and one behind each leg of the rider; in these the mail was placed. Three of these pockets were locked and opened en route at military posts and at Salt Lake City, and under no circumstances at any other place. The fourth was for way-stations, for which each station-keeper had a key, and also contained a way-bill, or time-card, on which a record of arrival and departure was kept. The same mochila was transferred from pony to pony and from rider to rider until it was carried from one terminus to the other. The letters, before being placed in the pockets, were wrapped in oiled silk to preserve them from moisture. The maximum weight of any one mail was twenty pounds; but this was rarely reached. The charges were originally $5 for each letter of one half-ounce or less; but afterward this was reduced to $2.50 for each letter not exceeding one half-ounce, this being in addition to the regular United States postage. Specially made light-weight paper was generally used to reduce the expense. Special editions of the Eastern newspapers were printed on tissue-paper to enable them to reach subscribers on the Pacific coast. This, however, was more as an advertisement, there being little demand for them at their necessarily large price.

At first, stations averaged 25 miles apart, and each rider covered three stations, or 75 miles, daily. Later, stations were established at intermediate points, reducing the distance between them, in some cases, to 10 miles, the distance between stations being regulated by the character of the country. This change was made in the interest of quicker time, it having been demonstrated that horses could not be kept at the top of their speed for so great a distance as 25 miles. At the stations, relays of horses were kept, and the station-keeper's duties included having a pony ready bridled and saddled half an hour before the express was due. Upon approaching a station, the rider would loosen the mochila from his saddle, so that he could leap from his pony as soon as he reached the station, throw the mochila over the saddle of the fresh horse, jump on, and ride off. Two minutes was the maximum time allowed at stations, whether it was to change riders or horses. At relay-stations where riders were changed the incoming man would unbuckle his mochila before arriving, and hand it to his successor, who would start off on a lope as soon as his hand grasped it. Time was seldom lost at stations. Station-keepers and relay-riders were always on the lookout. In the daytime the pony could be seen for a considerable distance, and at night a few well-known yells would bring everything into readiness in a very short time. As a rule, the riders would do 75 miles over their route west-bound one day, returning over the same distance with the first east-bound express.

Frequently, through the exigencies of the service, they would have to double their route the same day, or ride the one next to them, and even farther. For instance, "Buffalo Bill" (W. F. Cody) for a while had the route from Red Buttes, Wyoming, to Three Crossings, Nebraska, a distance of 116 miles. On one occasion, on reaching Three Crossings, he found that the rider for the next division had been killed the night before, and he was called upon to cover his route, 76 miles, until another rider could be employed. This involved a continuous ride of 384 miles without break, except for meals and to change horses. Again, "Pony Bob," another noted rider, covered the distance from Friday's Station to Smith's Creek, 185 miles, and back, including the trip over the Sierra Nevada, twice, at a time when the country was infested by hostile Indians. It eventually required, when the service got into perfect working order, 190 stations, 200 station-keepers and the same number of assistant station-keepers, 80 riders, and from 400 to 500 horses to cover the 1950 miles from St. Joseph to Sacramento. The riders were paid from $100 to $125 per month for their services. Located about every 200 miles were division agents to provide for emergencies, such as Indian raids, the stampeding of stock, etc., as well as to exercise general supervision over the service. One, and probably the most notorious, of these was Jack Slade, of unenviable reputation. For a long time he was located as division agent at the crossing of the Platte near Fort Kearney.

The riders were looked up to, and regarded as being "at the top of the heap." No matter what time of the day or of the night they were called upon, whether winter or summer, over mountains or across plains, raining or snowing, with rivers to swim or pleasant prairies to cross, through forests or over the burning desert, they must be ready to respond, and, though in the face of hostiles, ride their beat and make their time. To be late was their only fear, and to get in ahead of schedule their pride. There was no killing time for them, under any circumstances. The schedule was keyed up to what was considered the very best time that could be done, and a few minutes gained on it might be required to make up for a fall somewhere else. First-class horses were furnished, and there were no orders against bringing them in in a sweat. "Make your schedule," was the standing rule. While armed with the most effective weapon then known, the Colt revolver, they were not expected to fight, but to run away. Their weapons were to be used only in emergencies.

Considering the dangers encountered, the percentage of fatalities was extraordinarily small. Far more station employees than riders were killed by the Indians, and even of the latter more were killed off duty than on. This can be explained by the fact that the horses furnished the riders, selected as they were for speed and endurance, were far superior to the mounts of the Indians.

Many of the most noted of the frontiersmen of the sixties and seventies were schooled in the pony-express service. The life was a hard one. Setting aside the constant danger, the work was severe, both on riders and station employees. The latter were constantly on watch, herding their horses. Their diet frequently was reduced to wolf-mutton, their beverage to brackish water, a little tea or coffee being a great luxury, while the lonesome souls were nearly always out of tobacco.

The great feat of the pony-express service was the delivery of President Lincoln's inaugural address in 1861. Great interest was felt in this all over the land, foreshadowing as it did the policy of the administration in the matter of the Rebellion. In order to establish a record, as well as for an advertisement, the company determined to break all previous records, and to this end horses were led out from the different stations so as to reduce the distance each would have to run, and get the highest possible speed out of every animal. Each horse averaged only ten miles, and that at its very best speed. Every precaution was taken to prevent delay, and the result stands without a parallel in history; seven days and seventeen hours--one hundred and eighty-five hours--for 1950 miles, an average of 10.7 miles per hour. From St. Joseph to Denver, 665 miles were made in two days and twenty-one hours, the last 10 miles being accomplished in thirty-one minutes.

For More Information about the Pony Express in Kansas, visit these Websites: