Of the four classes of persons whose interrelations determined the condition of the frontier, none admitted that it desired to provoke Indian wars. The tribes themselves consistently professed a wish to be allowed to remain at peace. The Indian agents lost their authority and many of their perquisites during war time.

The army and the frontiersmen denied that they were belligerent. "I assert," wrote Custer, "and all candid persons familiar with the subject will sustain the assertion, that of all classes of our population the army and the people living on the frontier entertain the greatest dread of an Indian war, and are willing to make the greatest sacrifices to avoid its horrors." To fix the responsibility for the wars which repeatedly occurred, despite the protestations of amiability on all sides, calls for the examination of individual episodes in large number. It is easier to acquit the first two classes than the last two. There are enough instances in which the tribes were persuaded to promise and keep the peace to establish the belief that a policy combining benevolence, equity, and relentless firmness in punishing wrong-doers, white or red, could have maintained friendly relations with ease. The Indian agents were hampered most by their inability to enforce the laws intrusted to them for execution, and by the slowness of the Senate in ratifying agreements and of Congress in voting supplies. The frontiersmen, with their isolated homesteads lying open to surprise and destruction, would seem to be sincere in their protestations; yet repeatedly they thrust themselves as squatters upon lands of unquieted Indian title, while their personal relations with the red men were commonly marked by fear and hatred. The army, with greater honesty and better administration than the Indian Bureau, overdid its work, being unable to think of the Indians as anything but public enemies and treating them with an arbitrary curtness that would have been dangerous even among intelligent whites. The history of the southwest Indians, after the Sand Creek massacre, illustrates well how tribes, not specially ill-disposed, became the victims of circumstances which led to their destruction.

After the battle at Sand Creek, the southwest tribes agreed to a series of treaties in 1865 by which new reserves were promised them on the borderland of Kansas and Indian Territory. These treaties were so amended by the Senate that for a time the tribes had no admitted homes or rights save the guaranteed hunting privileges on the plains south of the Platte. They seem generally to have been peaceful during 1866, in spite of the rather shabby treatment which the neglect of Congress procured for them. In 1867 uneasiness became apparent. Agent E. W. Wynkoop, of Sand Creek fame, was now in charge of the Arapaho, Cheyenne, and Apache tribes in the vicinity of Fort Larned, on the Santa Fé trail in Kansas. In 1866 they had "complained of the government not having fulfilled its promises to them, and of numerous impositions practised upon them by the whites." Some of their younger braves had gone on the war-path. But Wynkoop claimed to have quieted them, and by March, 1867, thought that they were "well satisfied and quiet, and anxious to retain the peaceful relations now existing."

The military authorities at Fort Dodge, farther up the Arkansas and near the old Santa Fé crossing, were less certain than Wynkoop that the Indians meant well. Little Raven, of the Arapaho, and Satanta, "principal chief" of the Kiowa, were reported as sending in insulting messages to the troops, ordering them to cut no more wood, to leave the country, to keep wagons off the Santa Fé trail. Occasional thefts of stock and forays were reported along the trail. Custer thought that there was "positive evidence from the agents themselves" that the Indians were guilty, the trouble only being that Wynkoop charged the guilt on the Kiowa and Comanche, while J. H. Leavenworth, agent for these tribes, asserted their innocence and accused the wards of Wynkoop.

The Department of the Missouri, in which these tribes resided, was under the command of Major-general Winfield Scott Hancock in the spring of 1867. With a desire to promote the tranquillity of his command, Hancock prepared for an expedition on the plains as early as the roads would permit. He wrote of this intention to both of the agents, asking them to accompany him, "to show that the officers of the government are acting in harmony." His object was not necessarily war, but to impress upon the Indians his ability "to chastise any tribes who may molest people who are travelling across the plains." In each of the letters he listed the complaints against the respective tribes--failure to deliver murderers, outrages on the Smoky Hill route in 1866, alliances with the Sioux, hostile incursions into Texas, and the specially barbarous Box murder. In this last affair one James Box had been murdered by the Kiowas, and his wife and five daughters carried off. The youngest of these, a baby, died in a few days, the mother stated, and they "took her from me and threw her into a ravine." Ultimately the mother and three of the children were ransomed from the Kiowas after Mrs. Box and her eldest daughter, Margaret, had been passed around from chief to chief for more than two months. Custer wrote up this outrage with much exaggeration, but the facts were bad enough.

With both agents present, Hancock advanced to Fort Larned. "It is uncertain whether war will be the result of the expedition or not," he declared in general orders of March 26, 1867, thus admitting that a state of war did not at that time exist. "It will depend upon the temper and behavior of the Indians with whom we may come in contact. We go prepared for war and will make it if a proper occasion presents." The tribes which he proposed to visit were roaming indiscriminately over the country traversed by the Santa Fé trail, in accordance with the treaties of 1865, which permitted them, until they should be settled upon their reserves, to hunt at will over the plains south of the Platte, subject only to the restriction that they must not camp within ten miles of the main roads and trails. It was Hancock's intention to enforce this last provision, and more, to insist "upon their keeping off the main lines of travel, where their presence is calculated to bring about collisions with the whites."

The first conference with the Indians was held at Fort Larned, where the "principal chiefs of the Dog Soldiers of the Cheyennes" had been assembled by Agent Wynkoop. Leavenworth thought that the chiefs here had been very friendly, but Wynkoop criticised the council as being held after sunset, which was contrary to Indian custom and calculated "to make them feel suspicious." At this council General Hancock reprimanded the chiefs and told them that he would visit their village, occupied by themselves and an almost equal number of Sioux; which village, said Wynkoop, "was 35 miles from any travelled road." "Why don't he confine the troops to the great line of travel?" demanded Leavenworth, whose wards had the same privilege of hunting south of the Arkansas that those of Wynkoop had between the Arkansas and the Platte. So long as they camped ten miles from the roads, this was their right.

Contrary to Wynkoop's urgings, Hancock led his command from Fort Larned on April 13, 1867, moving for the main Arapaho, Cheyenne, and Sioux village on Pawnee Fork, thirty-five miles west of the post. With cavalry, infantry, artillery, and a pontoon train, it was hard for him to assume any other appearance than that of war. Even the General's particular assurance, as Custer puts it, "that he was not there to make war, but to promote peace," failed to convince the chiefs who had attended the night council. It was not a pleasant march. The snow was nearly a foot deep, fodder was scarce, and the Indian disposition was uncertain. Only a few had come in to the Fort Larned conference, and none appeared at camp after the first day's march. After this refusal to meet him, Hancock marched on to the village, in front of which he found some three hundred Indians drawn up in battle array. Fighting seemed imminent, but at last Roman Nose, Bull Bear, and other chiefs met Hancock between the lines and agreed upon an evening conference. It developed that the men alone were left at the Indian camp. Women and children, with all the movables they could handle, had fled out upon the snowy plains at the approach of the troops. Fear of another Sand Creek had caused it, said Wynkoop. But Hancock chose to regard this as evidence of a treacherous disposition, demanded that the fugitives return at once, and insisted upon encamping near the village against the protest of the chiefs. Instead of bringing back their people, the men themselves abandoned the village that evening, while Hancock, learning of the flight, surrounded and took possession of it. The next morning, April 15, Custer was sent with cavalry in pursuit of the flying bands. Depredations occurring to the north of Pawnee Fork within a day or two, Hancock burned the village in retaliation and proceeded to Fort Dodge. Wynkoop insisted that the Cheyenne and Arapaho had been entirely innocent and that these injuries had been committed by the Sioux. "I have no doubt," he wrote, "but that they think that war has been forced upon them."

When Hancock started upon the plains, there was no war, but there was no doubt about its existence as the spring advanced. When the Peace Commissioners of this year came with their protestations of benevolence for the Great Father, it was small wonder that the Cheyenne and Arapaho had to be coaxed into the camp on the Medicine Lodge Creek. And when the treaties there made failed of prompt execution by the United States, the war naturally dragged on in a desultory way during 1868 and 1869.

In the spring of 1868 General Sheridan, who had succeeded Hancock in command of the Department of the Missouri, visited the posts at Fort Larned and Fort Dodge. Here on Pawnee and Walnut creeks most of the southwest Indians were congregated. Wynkoop, in February and April, reported them as happy and quiet. They were destitute, to be sure, and complained that the Commissioners at Medicine Lodge had promised them arms and ammunition which had not been delivered. Indeed, the treaty framed there had not yet been ratified. But he believed it possible to keep them contented and wean them from their old habits. To Sheridan the situation seemed less happy. He declined to hold a council with the complaining chiefs on the ground that the whole matter was yet in the hands of the Peace Commission, but he saw that the young men were chafing and turbulent and that frontier hostilities would accompany the summer buffalo hunt.

There is little doubt of the destitution which prevailed among the plains tribes at this time. The rapid diminution of game was everywhere observable. The annuities at best afforded only partial relief, while Congress was irregular in providing funds. Three times during the spring the Commissioner prodded the Secretary of the Interior, who in turn prodded Congress, with the result that instead of the $1,000,000 asked for $500,000 were, in July, 1868, granted to be spent not by the Indian Office, but by the War Department. Three weeks later General Sherman created an organization for distributing this charity, placing the district south of Kansas in command of General Hazen. Meanwhile, the time for making the spring issues of annuity goods had come. It was ordered in June that no arms or ammunition should be given to the Cheyenne and Arapaho because of their recent bad conduct; but in July the Commissioner, influenced by the great dissatisfaction on the part of the tribes, and fearing "that these Indians, by reason of such non-delivery of arms, ammunition, and goods, will commence hostilities against the whites in their vicinity, modified the order and telegraphed Agent Wynkoop that he might use his own discretion in the matter: "If you are satisfied that the issue of the arms and ammunition is necessary to preserve the peace, and that no evil will result from their delivery, let the Indians have them." A few days previously on July 20, Wynkoop had issued the ordinary supplies to his Arapaho and Apache, his Cheyenne refusing to take anything until they could have the guns as well. "They felt much disappointed, but gave no evidence of being angry ... and would wait with patience for the Great Father to take pity upon them." The permission from the Commissioner was welcomed by the agent, and approved by Thomas Murphy, his superintendent. Murphy had been ordered to Fort Larned to reënforce Wynkoop's judgment. He held a council on August 1 with Little Raven and the Arapaho and Apache, and issued them their arms. "Raven and the other chiefs then promised that these arms should never be used against the whites, and Agent Wynkoop then delivered to the Arapahoes 160 pistols, 80 Lancaster rifles, 12 kegs of powder, 1-1/2 keg of lead, and 15,000 caps; and to the Apaches he gave 40 pistols, 20 Lancaster rifles, 3 kegs of powder, 1/2 keg of lead, and 5000 caps." The Cheyenne came in a few days later for their share, which Wynkoop handed over on the 9th. "They were delighted at receiving the goods," he reported, "particularly the arms and ammunition, and never before have I known them to be better satisfied and express themselves as being so well contented." The fact that within three days murders were committed by the Cheyenne on the Solomon and Saline forks throws doubt upon the sincerity of their protestations.

The war party which commenced the active hostilities of 1868 at a time so well calculated to throw discredit upon the wisdom of the Indian Office, had left the Cheyenne village early in August, "smarting under their _supposed_ wrongs," as Wynkoop puts it. They were mostly Cheyenne, with a small number of Arapaho and a few visiting Sioux, about 200 in all. Little Raven's son and a brother of White Antelope, who died at Sand Creek, were with them; Black Kettle is said to have been their leader. On August 7 some of them spent the evening at Fort Hays, where they held a powwow at the post. "Black Kettle loves his white soldier brothers, and his heart feels glad when he meets them and shakes their hands in friendship," is the way the post-trader, Hill P. Wilson, reported his speech. "The white soldiers ought to be glad all the time, because their ponies are so big and so strong, and because they have so many guns and so much to eat.... All other Indians may take the war trail, but Black Kettle will forever keep friendship with his white brothers." Three nights later they began to kill on Saline River, and on the 11th they crossed to the Solomon. Some fifteen settlers were killed, and five women were carried off. Here this particular raid stopped, for the news had got abroad, and the frontier was instantly in arms. Various isolated forays occurred, so that Sheridan was sure he had a general war upon his hands. He believed nearly all the young men of the Cheyenne, Kiowa, Arapaho, and Comanche to be in the war parties, the old women, men, and children remaining around the posts and professing solicitous friendship. There were 6000 potential warriors in all, and that he might better devote himself to suppressing them, Sheridan followed the Kansas Pacific to its terminus at Fort Hays and there established his headquarters in the field.

The war of 1868 ranged over the whole frontier south of the Platte trail. It influenced the Peace Commission, at its final meeting in October, 1868, to repudiate many of the pacific theories of January and recommend that the Indians be handed over to the War Department. Sheridan, who had led the Commission to this conclusion, was in the field directing the movement. His policy embraced a concentration of the peaceful bands south of the Arkansas, and a relentless war against the rest. It is fairly clear that the war need not have come, had it not been for the cross-purposes ever apparent between the Indian Office and the War Department, and even within the War Department itself.

At Fort Hays, Sheridan prepared for war. He had, at the start, about 2600 men, nearly equally divided among cavalry and infantry. Believing his force too small to cover the whole plains between Fort Hays and Denver, he called for reënforcements, receiving a part of the Fifth Cavalry and a regiment of Kansas volunteers. With enthusiasm this last addition was raised among the frontiersmen, where Indian fighting was popular; the governor of the state resigned his office to become its colonel. September and October were occupied in getting the troops together, keeping the trails open for traffic, and establishing, about a hundred miles south of Fort Dodge, a rendezvous which was known as Camp Supply. It was the intention to protect the frontier during the autumn, and to follow up the Indian villages after winter had fallen, catching the tribes when they would be concentrated and at a disadvantage.

On October 15, 1868, Sherman, just from the Chicago meeting of the Peace Commissioners and angry because he had there been told that the army wanted war, gave Sheridan a free hand for the winter campaign. "As to 'extermination,' it is for the Indians themselves to determine. We don't want to exterminate or even to fight them.... The present war ... was begun and carried on by the Indians in spite of our entreaties and in spite of our warnings, and the only question to us is, whether we shall allow the progress of our western settlements to be checked, and leave the Indians free to pursue their bloody career, or accept their war and fight them.... We ... accept the war ... and hereby resolve to make its end final.... I will say nothing and do nothing to restrain our troops from doing what they deem proper on the spot, and will allow no mere vague general charges of cruelty and inhumanity to tie their hands, but will use all the powers confided to me to the end that these Indians, the enemies of our race and of our civilization, shall not again be able to begin and carry on their barbarous warfare on any kind of pretext that they may choose to allege."

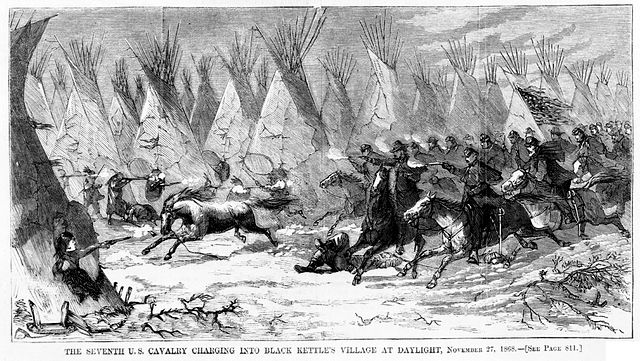

The plan of campaign provided that the main column, Custer in immediate command, should march from Fort Hays directly against the Indians, by way of Camp Supply; two smaller columns were to supplement this, one marching in on Indian Territory from New Mexico, and the other from Fort Lyon on the old Sand Creek reserve. Detachments of the chief column began to move in the middle of November, Custer reaching the depot at Camp Supply ahead of the rest, while the Kansas volunteers lost themselves in heavy snow-storms. On November 23 Custer was ordered out of Camp Supply, on the north fork of the Canadian, to follow a fresh trail which led southwest towards the Washita River, near the eastern line of Texas. He pushed on as rapidly as twelve inches of snow would allow, discovering in the early morning of November 27 a large camp in the valley of the Washita.

Battle of Washita from Harper's Weekly, December 19, 1868. Image courtesy of Wikimedia

Battle of Washita from Harper's Weekly, December 19, 1868. Image courtesy of Wikimedia

It was Black Kettle's camp of Cheyenne and Arapaho that they had found in a strip of heavy timber along the river. After reconnoitring Custer divided his force into four columns for simultaneous attacks upon the sleeping village. At daybreak "my men charged the village and reached the lodges before the Indians were aware of our presence. The moment the charge was ordered the band struck up 'Garry Owen,' and with cheers that strongly reminded me of scenes during the war, every trooper, led by his officer, rushed towards the village." For several hours a promiscuous fight raged up and down the ravine, with Indians everywhere taking to cover, only to be prodded out again. Fifty-one lodges in all fell into Custer's hands; 103 dead Indians, including Black Kettle himself, were found later. "We captured in good condition 875 horses, ponies, and mules; 241 saddles, some of very fine and costly workmanship; 573 buffalo robes, 390 buffalo skins for lodges, 160 untanned robes, 210 axes, 140 hatchets, 35 revolvers, 47 rifles, 535 pounds of powder, 1050 pounds of lead, 4000 arrows and arrowheads, 75 spears, 90 bullet moulds, 35 bows and quivers, 12 shields, 300 pounds of bullets, 775 lariats, 940 buckskin saddle-bags, 470 blankets, 93 coats, 700 pounds of tobacco."

As the day advanced, Custer's triumph seemed likely to turn into defeat. The Cheyenne village proved to be only the last of a long string of villages that extended down the Washita for fifteen miles or more, and whose braves rode up by hundreds to see the fight. A general engagement was avoided, however, and with better luck and more discretion than he was one day to have, Custer marched back to Camp Supply on December 3, his band playing gayly the tune of battle, "Garry Owen." The commander in his triumphal procession was followed by his scouts and trailers, and the captives of his prowess--a long train of Indian widows and orphans.

The decisive blow which broke the power of the southwest tribes had been struck, and Black Kettle had carried on his last raid,--if indeed he had carried on this one at all--but as the reports came in it became evident that the merits of the triumph were in doubt. The Eastern humanitarians were shocked at the cold-blooded attack upon a camp of sleeping men, women, and children, forgetting that if Indians were to be fought this was the most successful way to do it, and was no shock to the Indians' own ideals of warfare and attack. The deeper question was whether this camp was actually hostile, whether the tribes had not abandoned the war-path in good faith, whether it was fair to crush a tribe that with apparent earnestness begged peace because it could not control the excesses of some of its own braves. It became certain, at least, that the War Department itself had fallen victim to that vice with which it had so often reproached the Indian Office--failure to produce a harmony of action among several branches of the service.

The Indian Office had no responsibility for the battle of the Washita. It had indeed issued arms to the Cheyenne in August, but only with the approval of the military officer commanding Forts Larned and Dodge, General Alfred Sully, "an officer of long experience in Indian affairs." In the early summer all the tribes had been near these forts and along the Santa Fé trail. After Congress had voted its half million to feed the hungry, Sherman had ordered that the peaceful hungry among the southern tribes should be moved from this locality to the vicinity of old Fort Cobb, in the west end of Indian Territory on the Washita River.

During September, while Sheridan was gathering his armament at Fort Hays, Sherman was ordering the agents to take their peaceful charges to Fort Cobb. With the major portion of the tribes at war it would be impossible for the troops to make any discrimination unless there should be an absolute separation between the well-disposed and the warlike. He proposed to allow the former a reasonable time to get to their new abode and then beg the President for an order "declaring all Indians who remain outside of their lawful reservations" to be outlaws. He believed that by going to war these tribes had violated their hunting rights. Superintendent Murphy thought he saw another Sand Creek in these preparations. Here were the tribes ordered to Fort Cobb; their fall annuity goods were on the way thither for distribution; and now the military column was marching in the same direction.

In the meantime General W. B. Hazen had arrived at Fort Cobb on November 7 and had immediately voiced his fear that "General Sheridan, acting under the impression of hostiles, may attack bands of Comanche and Kiowa before they reach this point." He found, however, most of these tribes, who had not gone to war this season, encamped within reach on the Canadian and Washita rivers,--5000 of the Comanche and 1500 of the Kiowa. Within a few days Cheyenne and Arapaho began to join the settlements in the district, Black Kettle bringing in his band to the Washita, forty miles east of Antelope Hills, and coming in person to Fort Cobb for an interview with General Hazen on November 20.

"I have always done my best," he protested, "to keep my young men quiet, but some will not listen, and since the fighting began I have not been able to keep them all at home. But we all want peace." To which added Big Mouth, of the Arapaho: "I came to you because I wish to do right.... I do not want war, and my people do not, but although we have come back south of the Arkansas, the soldiers follow us and continue fighting, and we want you to send out and stop these soldiers from coming against us."

To these, General Hazen, fearful as he was of an unjust attack, responded with caution. Sherman had spoken of Fort Cobb in his orders to Sheridan, as "aimed to hold out the olive branch with one hand and the sword in the other. But it is not thereby intended that any hostile Indians shall make use of that establishment as a refuge from just punishment for acts already done. Your military control over that reservation is as perfect as over Kansas, and if hostile Indians retreat within that reservation, ... they may be followed even to Fort Cobb, captured, and punished." It is difficult to see what could constitute the fact of peaceful intent if coming in to Fort Cobb did not. But Hazen gave to Black Kettle cold comfort: "I am sent here as a peace chief; all here is to be peace; but north of the Arkansas is General Sheridan, the great war chief, and I do not control him; and he has all the soldiers who are fighting the Arapahoes and Cheyennes.... If the soldiers come to fight, you must remember they are not from me, but from that great war chief, and with him you must make peace.... I cannot stop the war.... You must not come in again unless I send for you, and you must keep well out beyond the friendly Kiowas and Comanches." So he sent the suitors away and wrote, on November 22, to Sherman for more specific instructions covering these cases. He believed that Black Kettle and Big Mouth were themselves sincere, but doubted their control over their bands. These were the bands which Custer destroyed before the week was out, and it is probable that during the fight they were reënforced by braves from the friendly lodges of Satanta's Kiowa and Little Raven's Arapaho.

Whatever might have been a wise policy in treating semi-hostile Indian tribes, this one was certainly unsatisfactory. It is doubtful whether the war was ever so great as Sherman imagined it. The injured tribes were unquestionably drawn to Fort Cobb by a desire for safety; the army was in the position of seeming to use the olive branch to assemble the Indians in order that the sword might the better disperse them. There is reasonable doubt whether Black Kettle had anything to do with the forays. Murphy believed in him and cited many evidences of his friendly disposition, while Wynkoop asserted positively that he had been encamped on Pawnee Fork all through the time when he was alleged to have been committing depredations on the Saline. The army alone had been no more successful in producing obvious justice than the army and Indian Office together had been. Yet whatever the merits of the case, the power of the Cheyenne and their neighbors was permanently gone.

During the winter of 1868-1869 Sheridan's army remained in the vicinity of Fort Cobb, gathering the remnants of the shattered tribes in upon their reservation. The Kiowa and Comanche were placed at last on the lands awarded them at the Medicine Lodge treaties, while the Arapaho and Cheyenne once more had their abiding-place changed in August, 1869, and were settled down along the upper waters of the Washita, around the valley of their late defeat.

The long controversy between the War and Interior departments over the management of the tribes entered upon a new stage with the inauguration of Grant in 1869. One of the earliest measures of his administration was a bill erecting a board of civilian Indian commissioners to advise the Indian Department and promote the civilization of the tribes. A generous grant of two millions accompanied the act. More care was used in the appointment of agents than had hitherto been taken, and the immediate results seemed good when the Commissioner wrote his annual report in December, 1869. But the worst of the troubles with the Indians of the plains was over, so that without special effort peace could now have been the result.