After the high-water experience, our things were scarcely dry before I found, for the second time, what it was to be under the complete subjection of military rule. The fiat was issued that we women must depart from camp and return to garrison, as it was considered unsafe for us to remain.

It was an intense disappointment; for though Fort Hays and our camp were more than dreary after the ravages of the storm, to leave there meant cutting myself off from any other chance that might come in my way of joining my husband, or of seeing him at our camp. Two of the officers and an escort of ten mounted men, going to Fort Harker on duty, accompanied our little cortege of departing women. At the first stage-station the soldiers all dismounted as we halted, and managed by some pretext to get into the dug-out and buy whiskey. Not long after we were again _en route_ I saw one of the men reel on his saddle, and he was lifted into the wagon that carried forage for the mules and horses. One by one, all were finally dumped into the wagons by the teamsters, who fortunately were sober, and the troopers' horses were tied behind the vehicles, and we found ourselves without an escort. Plains whiskey is usually very rapid in its effect, but the stage-station liquor was concocted from drugs that had power to lay out even a hard-drinking old cavalryman like a dead person in what seemed no time at all. Eliza said "they only needed to smell it, 'twas so deadly poison." A barrel of tolerably good whiskey sent from the States was, by the addition of drugs, made into several barrels after it reached the Plains.

The hours of that march seemed endless. We were helpless, and knew that we were going over ground that was hotly contested by the red man. We rose gradually to the summit of each divide, and looked with anxious eyes into every depression; but we were no sooner relieved to find it safe, than my terrors began as to what the next might reveal. When we came upon an occasional ravine, it represented to my frightened soul any number of Indians in ambush.

In that country the air is so clear that every object on the brow of a small ascent of ground is silhouetted against the deep blue of the sky. The Indians place little heaps of stones on these slight eminences, and lurk behind them to watch the approach of troops. Every little pile of rocks seemed, to my strained eyes, to hide the head of a savage. They even appeared to move, and this effect was heightened by the waves of heat that hover over the surface of the earth under that blazing sun. I was thoroughly frightened, doubtless made much more so because I had nothing else to think of, as the end of the journey would not mean for me what the termination of ever so dangerous a march would have been in the other direction. Had I been going over such country to join my husband, the prospect would have put temporary courage into every nerve. During the hours of daylight the vigilance of the officers was unceasing. They knew that one of the most hazardous days of their lives was upon them. They felt intensely the responsibility of the care of us; and I do not doubt, gallant as they were, that they mentally pronounced anathemas upon officers who had wanted to see their wives so badly that they had let them come into such a country. When we had first gone over the route, however, its danger was not a circumstance to this time. Our eyes rarely left the horizon; they were strained to discern signs that had come to be familiar, even by our hearing them discussed so constantly; and we, still novices in the experience of that strange country, had seen for ourselves enough to prove that no vigilance was too great. If on the monotonous landscape a whirl of dust arose, instantly it was a matter of doubt whether it meant our foe or one of the strange eccentricities of that part of the world. The most peculiar communions are those that the clouds seem to have with the earth, which result in a cone of dust whirlpooling itself straight in the air, while the rest of the earth is apparently without commotion, bearing no relation to the funnel that seems to struggle upward and be dissolved into the passing wind. With what intense concentration we watched to see it so disappear! If the puff of dust continued to spread, the light touching it into a deeper yellow, and finally revealing some darker shades, and at last shaping itself into dusky forms, we were in agony of suspense until the field-glasses proved that it was a herd of antelopes fleeing from our approach. There literally seemed to be not one inch of the way that the watchful eyes of the officers, the drivers, or we women were not strained to discover every object that specked the horizon or rose on the trail in front of us.

With all the terror and suspense of those dragging miles, I could not be insensible to the superb and riotous colors of the wild flowers that carpeted our way. It was the first time that I had ever been where the men could not be asked, and were not willing, to halt or let me stop and gather one of every kind. The gorgeousness of the reds and orange of those prairie blossoms was a surprise to me. I had not dreamed that the earth could so glow with rich tints. The spring rains had soaked the ground long enough to start into life the wonderful dyes that for a brief time emblazon the barren wilderness. The royal livery floats but a short period over their temporary domain, for the entire cessation of even the night dews, and the intensity of the scorching sun, shrivels the vivid, flaunting, feathery petals, and burns the venturesome roots down into the earth. What presuming things, to toss their pennants over so inhospitable a land! But what a boon to travelers like ourselves to see, for even the brief season, some tint besides the burnt umber and yellow ochre of those plains! All the short existence of these flowers is condensed into the color, tropical in richness; not one faint waft of perfume floated on the air about us. But it was all we ought to have asked, that their brilliant heads appear out of such soil. This has served to make me very appreciative of the rich exhalation of the Eastern gardens. I do not dare say what the first perfume of the honeysuckle is to me, each year now; nor would I infringe upon the few adjectives vouchsafed the use of a conventional Eastern woman when, as it happened this year, the orange blossoms, white jessamine and woodbine wafted their sweet breaths in my face as a welcome from one garden to which good fortune led me. I remember the starvation days of that odorless life, when, seeing rare colors, we instantly expected rich odors, but found them not, and I try to adapt myself to the customs of the country, and not rave, but, like the children, keep up a mighty thinking.

Buffalo, antelope, blacktail deer, coyote, jack-rabbits, scurried out of our way on that march, and we could not stop to follow. I was looking always for some new sight, and, after the relief that I felt when each object as we neared it turned out to be harmless, was anxious to see a drove of wild horses. There were still herds to be found between the Cimarron and the Arkansas rivers. The General told me of seeing one of the herds on a march, spoke with great admiration and enthusiasm of the leader, and described him as splendid in carriage, and bearing his head in the proudest, loftiest manner as he led his followers. They were not large; they must have been the Spanish pony of Cortez' time, as we know that the horse is not indigenous to America. The flowing mane and tail, the splendid arch of the neck, and the proud head carried so loftily, give the wild horses a larger, taller appearance than is in reality theirs. Few ever saw the droves of wild horses more than momentarily. They run like the wind.

Illustration: A BUFFALO AT BAY. (FROM A PHOTOGRAPH TAKEN ON THE SPOT.)

After the introduction of the dromedary into Texas, many years since, for transportation of supplies over that vast territory, one was brought up to Colorado. Because of the immense runs it could make without water, it was taken into the region frequented by the wild horses, and when they were sighted, the dromedary was started in pursuit. Two were run down, and found to be nearly dead when overtaken. But the poor dromedary suffered so from the prickly-pear filling the soft ball of its feet, that no farther pursuit could ever be undertaken.

I had to be content with the General's description, for no wild horses came in our way. But there was enough to satisfy any one in the way of game. The railroad had not then driven to the right and left the inhabitants of that vast prairie. Our country will never again see the Plains dotted with game of all sorts. The railroad stretches its iron bands over these desert wastes, and scarcely a skulking coyote, hugging the ground and stealing into gulches, can be discovered during a whole day's journey.

As the long afternoon was waning, we were allowed to get out and rest a little while, for we had reached what was called the "Home Station," so called because at this place there was a woman, then the only one along the entire route. I looked with more admiration than I could express on this fearless creature, long past the venturesome time of early youth, when some dare much for excitement. She was as calm and collected as her husband, whom she valued enough to endure with him this terrible existence. How good the things tasted that she cooked, and how different the dooryard looked from those of the other stations! Then she had a baby antelope, and the apertures that served as windows had bits of white curtains, and, altogether, I did not wonder that over the hundreds of miles of stage-route the Home Station was a place the men looked forward to as the only reminder of the civilization that a good woman establishes about her. There was an awful sight, though, that riveted my eyes as we prepared to go on our journey, and the officers could not, by any subterfuge, save us from seeing it. It was a disabled stage-coach, literally riddled with bullets, its leather hanging in shreds, and the woodwork cut into splinters. When there was no further use of trying to conceal it from us, we were told that this stage had come into the station in that condition the day before, and the fight that the driver and mail-carrier had been through was desperate. There was no getting the sight of that vehicle out of my mind during the rest of the journey. What a friend the darkness seemed, as it wrapped its protecting mantle about us, after the long twilight ended! yet it was almost impossible to sleep, though we knew we were comparatively safe till dawn. At daybreak the officers asked us to get out, while the mules were watered and fed, and rest ourselves, and though I had been so long riding in a cramped position, I would gladly have declined. Cleanliness is next to godliness, and, one of our friends said, "With a woman, it is before godliness," yet that was an occasion when I would infinitely have preferred to be numbered with the great unwashed. However, a place in the little stream at the foot of the gully was pointed out, and we took our tin basin and towel and freshened ourselves by this early toilet; but there was no lingering to prink, even on the part of the pretty Diana. Our eyes were staring on all sides, with a dread impossible to quell, and back into the ambulance we climbed, not breathing a long, free breath until the last of those terrible eighty miles were passed, and we beheld with untold gratitude the roofs of the quarters at Fort Harker.

I felt that we had trespassed as much as we ought upon the hospitality of the commanding officer of the post, and begged to be allowed to sleep in our ambulance while we remained in the garrison. He consented, under protest, and our wagon and that of Mrs. Gibbs were placed in the space between two Government storehouses, and a tarpaulin was stretched over the two. Eliza prepared our simple food over a little camp-fire. While the weather remained good, this was a very comfortable camp for us--but when, in Kansas, do the elements continue quiet for twenty-four hours? In the darkest hour of the blackest kind of night the wind rose into a tempest, rushing around the corners of the buildings, hunting out with pertinacity, from front and rear, our poor little temporary home. The tarpaulin was lifted on high, and with ropes and picket-pins thrashing on the canvas it finally broke its last moorings and soared off into space. The rain beat in the curtains of the ambulance and soaked our blankets. Still, we crept together on the farther side of our narrow bed and, rolled up in our shawls, tried to hide our eyes from the lightning, and our ears from the roar of the storm as it swept between the sheltering buildings and made us feel as if we were camping in a tunnel.

Our neighbor's dog joined his voice with the sobs and groans of the wind, while in the short intervals of quiet we called out, trying to get momentary courage from speech with each other. The curtain at the end of the ambulance jerked itself free, and in came a deluge of rain from a new direction. Pins, strings and four weak hands holding their best, did no earthly good, and I longed to break all military rule and scream to the sentinel. Not to speak to a guard on post is one of the early lessons instilled into every one in military life. It required such terror of the storm and just such a drenching as we were getting, even to harbor a thought of this direct disobedience of orders. Clutching the wagon-curtains and watching the soldier, who was revealed by the frequent flashes of lightning as he tramped his solitary way, might have gone on for some time without the necessary courage coming to call him, but a new departure of the wind suddenly set us in motion, and I found that we were spinning down the little declivity back of us, with no knowledge of when or where we would stop. Then I did scream, and the peculiar shrillness of a terrified woman's voice reached the sentinel. Blessed breaker of his country's laws! He answered to a higher one, which forbids him to neglect a woman in danger, and left his beat to run to our succor.

Our wagon was dragged back by some of the soldiers on night duty at the guard-house, and was newly pinioned to the earth with stronger picket-pins and ropes, but sleep was murdered for that night. Of course the guard reported to the commanding officer, as is their rule, and soon a lantern or two came zigzagging over the parade-ground in our direction, and the officers called to know if they could speak with us. There was no use in arguing. Mrs. Gibbs and her boys, Diana drenched and limp as to clothes, and I decidedly moist, were fished out of our watery camp-beds, and with our arms full of apparel and satchels, we followed the officers in the dark to the dry quarters, that we had tried our best to decline rather than make trouble.

It was decided that we must proceed to Fort Riley, as there were no quarters to offer us; and tent-life, as I have tried to describe it, had its drawbacks in the rainy season. Had it not meant for me ninety miles farther separation from my husband, seemingly cut off from all chance of joining him again, I would have welcomed the plan of going back, as Fort Harker was at this time the most absolutely dismal and melancholy spot I remember ever to have seen. A terrible and unprecedented calamity had fallen upon the usually healthful place, for cholera had broken out, and the soldiers were dying by platoons. I had been accustomed to think, in all the vicissitudes that had crowded themselves into these few months, whatever else we were deprived of, we at least had a climate unsurpassed for salubrity, and I still think so. For some strange reason, right out in the midst of that wide, open plain, with no stagnant water, no imperfect drainage, no earthly reason, it seemed to us, this epidemic had suddenly appeared, and in a form so violent that a few hours of suffering ended fatally. Nobody took dying into consideration out there in those days; all were well and able-bodied, and almost everyone was young who ventured into that new country, so no lumber had been provided to make coffins. For a time the rudest receptacles were hammered together, made out of the hardtack boxes. Almost immediate burial took place, as there was no ice, nor even a safe place to keep the bodies of the unfortunate victims. It was absolutely necessary, but an awful thought nevertheless, this scurrying under the ground of the lately dead, perhaps only wrapped in a coarse gray army blanket, and with the burial service hurriedly read, for all were needed as nurses, and time was too precious to say even the last words, except in haste. The officers and their families did not escape, and sorrow fell upon every one when an attractive young woman who had dared everything in the way of hardships to follow her husband, was marked by that terrible finger which bade her go alone into the valley of death. In the midst of this scourge, the Sisters of Charity came. Two of them died, and afterward a priest, but they were replaced by others, who remained until the pestilence had wrought its worst; then they gathered the orphaned children of the soldiers together, and returned with them to the parent house of their Order in Leavenworth.

I would gladly have these memories fade out of my life, for the scenes at that post have no ray of light except the heroic conduct of the men and women who stood their ground through the danger. I cannot pass by those memorable days in the early history of Kansas without my tribute to the brave officers and men who went through so much to open the way for settlers. I lately rode through the State, which seemed when I first saw it a hopeless, barren waste, and found the land under fine cultivation, the houses, barns and fences excellently built, cattle in the meadows, and, sometimes, several teams ploughing in one field. I could not help wondering what the rich owners of these estates would say, if I should step down from the car and give them a little picture of Kansas, with the hot, blistered earth, dry beds of streams, and soil apparently so barren that not even the wild-flowers would bloom, save for a brief period after the spring rains. Then add pestilence, Indians, and an undisciplined, mutinous soldiery who composed our first recruits, and it seems strange that our officers persevered at all. I hope the prosperous ranchman will give them one word of thanks as he advances to greater wealth, since but for our brave fellows the Kansas Pacific Railroad could not have been built; nor could the early settlers, daring as they were, have sowed the seed that now yields them such rich harvests.

We had no choice about leaving Fort Harker. There was no accommodation for us--indeed we would have hampered the already overworked officers and men; so we took our departure for Fort Riley. There we found perfect quiet; the negro troops were reduced to discipline, and everything went on as if there were no such thing as the dead and the dying that we had left a few hours before. There was but a small garrison, and we easily found empty quarters, that were lent to us by the commanding officer.

Then the life of watching and waiting, and trying to possess my soul in patience, began again, and my whole day resolved itself into a mental protest against the slowness of the hours before the morning mail could be received. It was a doleful time for us; but I remember no uttered complaints as such, for we silently agreed they would weaken our courage. If tears were shed, they fell on the pillow, where the blessed darkness came to absolve us from the rigid watchfulness that we tried to keep over our feelings. My husband gladdened many a dark day by the cheeriest letters. How he ever managed to write so buoyantly was a mystery when I found afterward what he was enduring. I rarely had a letter with even so much as a vein of discontent, during all our separations. At that time came two that were strangely in contrast to all the brave, encouraging missives that had cheered my day. The accounts of cholera met our regiment on their march into the Department of the Platte; and the General, in the midst of intense anxiety, with no prospect of direct communication, assailed by false reports of my illness, at last showed a side of his character that was seldom visible. His suspense regarding my exposure to pestilence, and his distress over the fright and danger I had endured at the time of the flood at Fort Hays, made his brave spirit quail, and there were desperate words written, which, had he not been relieved by news of my safety, would have ended in his taking steps to resign. Even he, whom I scarcely ever knew to yield to discouraging circumstances, wrote that he could not and would not endure such a life.

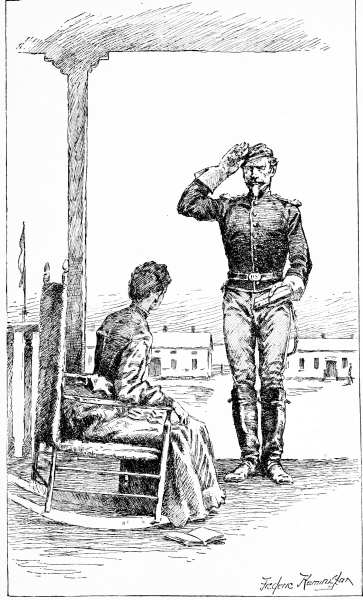

Our days at Fort Riley had absolutely nothing to vary them after mail time. I sat on the gallery long before the time of distribution, pretending to sew or read, but watching constantly for the door of the office to yield up next to the most important man in the wide world to me. The soldier whose duty it was to bring the mail became so inflated by the eagerness with which his steps were watched, that it came near being the death of him when he joined his company in the autumn, and was lost in its monotonous ranks. He was a ponderous, lumbering fellow in body and mind, who had been left behind by his captain, ostensibly to take care of the company property, but I soon found there was another reason, as his wits had for some time been unsettled, that is--giving him the benefit of a doubt--if he ever had any. Addled as his brain might be, the remnant of intelligence was ample in my eyes if it enabled him to make his way to our door. As he belonged to the Seventh Cavalry, he considered that everything at the post must be subservient to my wish, when in reality I was dependent for a temporary roof on the courtesy of the infantry officer in command. If I even met him in our walks, he seemed to swell to twice his size, and to feel that some of the odor of sanctity hung around him, whether he bore messages from the absent or not.

Illustration: THE ADDLED LETTER-CARRIER.

The contents of the mail-bag being divided, over six feet of anatomical and military perfection came stalking through the parade-ground. He would not demean himself to hasten, and his measured steps were in accordance with the gait prescribed in the past by his sergeant on drill. He appeared to throw his head back more loftily as he perceived that my eyes followed his creeping steps. He seemed to be reasoning. Did Napoleon ever run, the Duke of Wellington ever hasten, or General Scott quicken his gait or impair his breathing by undue activity, simply because an unreasoning, impatient woman was waiting somewhere for them to appear? It was not at all in accordance with his ideas of martial character to exhibit indecorous speed. The great and responsible office of conveying the letters from the officer to the quarters had been assigned to him, and nothing, he determined, should interfere with its being filled with dignity. His country looked to him as its savior. Only a casual and condescending thought was given to his comrades, who perhaps at that time were receiving in their bodies the arrows of Indian warriors. No matter how eagerly I eyed the great official envelope in his hand, which I knew well was mine, he persisted in observing all the form and ceremony that he had decided was suitable for its presentation. He was especially particular to assume the "first position of a soldier," as he drew up in front of me. The tone with which he addressed me was deliberate and grandiloquent. The only variation in his regulation manners was that he allowed himself to speak before he was spoken to. With the flourish of his colossal arm, in a salute that took in a wide semicircle of Kansas air, he said, "Good morning, Mrs. Major-General George Armstrong Custer." He was the only gleam of fun we had in those dismal days. He was a marked contrast to the disciplined enlisted man, who never speaks unless first addressed by his superiors, and who is modesty itself in demeanor and language in the presence of the officers' wives. The farewell salute of our mail-carrier was funnier than his approach. He wheeled on his military heel, and swung wide his flourishing arm, but the "right about face" I generally lost, for, after snatching my envelope from him, unawed by his formality, I fled into the house to hide, while I laughed and cried over the contents.