The Plains Indians were losing out. They saw their buffalo grounds growing smaller and smaller. The Sioux and Northern Cheyennes had not stopped the Union Pacific Railroad. It had cut the northern herd in two. The Cheyennes and Arapahos and Dog Soldiers from other tribes had not stopped the Kansas Pacific Railroad. In their last great raid they had been defeated at the battle of Beecher's Island, as the fight by Major Forsythe, at the Arikaree in September, 1868, was known. The Kansas Pacific had cut the southern herd in two. It was bringing swarms of white hunters into the Kansas buffalo range; they were slaughtering the game and wasting the meat.

Then, in 1872, still another iron road, the Atchison, Topeka & Santa Fe, pushed out, south of the Kansas Pacific, and took possession of the old Santa Fe Trail, the wagon-road up the Arkansas River. The wagon-road itself had been bad enough; for the emigrants were gathering all the fuel and killing and frightening the buffalo. The snorting engines and swift trains were worse. The buffalo were again split. From southern Kansas north into central Nebraska there was no place for the buffalo, and the Indian.

This year, 1872, the white hunters commenced to kill for the hides. They skinned the carcasses, and let the meat lie and rot, except the small portion that they ate. Many of the buffalo were only wounded; they staggered away, and died untouched. Many of the hides were spoiled. For each hide sent to market, and sold for maybe only $1.50, four other buffalo were wasted.

In 1873 the slaughter was increased. Regularly organized parties took the field. By trains and wagons the buffalo were easily and quickly found; the Atchison, Topeka & Santa Fe Railroad shipped out over two hundred and fifty thousand hides; the Kansas and Pacific and the Union Pacific twice as many. At the plains stations the bales of hides were piled as high as houses. In order to save time, the hides were yanked off by a rope and tackle and a team of horses. Almost five million pounds of meat were saved, and over three million pounds of bones for fertilizer; but the meat averaged only about seven pounds to each hide taken--and that was trifling. Evidently an enormous quantity of buffalo were still being wasted.

It was considered nothing at all to shoot a buffalo. So-called sportsmen bombarded right and left, and kept tally to see who should kill the most. Passengers and train-crews peppered away from coach, caboose and engine, and the trains did not even halt.

In 1874 there was a great difference to be noted among the herds. They were getting wild; the hunters laid in wait at the water-holes, and killed the buffalo that finally had to come in, to drink. In the three years, 1872-1873-1874, no less than 3,158,730 were killed by the white hunters; all the Indians together killed perhaps 1,215,000--but they used these for food, clothing, and in trade for other goods. A full million more of buffalo were taken out by wagon and pack horse. So this sums up over five million. The plains were white with skeletons; in places the air was foul with the odor of decaying meat.

The buffalo had two refuges from the white killer: one far in the north, in the Sioux country; the other far in the south, in the Comanche and Kiowa country of present Oklahoma and Texas.

By a treaty made in 1867 the United States had promised that white men should not hunt south of the Arkansas River. But in 1874, when the buffalo in Kansas and Nebraska had become scarcer, and the price of hides was so low that long chases and waits did not pay out, the hunters gave no attention to the treaty, and located their camps south of the river, in forbidden territory.

The Indians awakened to the fact that soon there would be no buffalo left for them. For years they had depended upon the buffalo, as food, and glue, and clothing and lodge covers. They had believed that the buffalo were the gift of the Great Spirit, who every spring brought fresh numbers out of holes in the Staked Plain of western Texas, to fill the ranks. Now the bad medicine of the whites was about to close these holes; the buffalo would come north no more.

In the spring of 1874 the Kiowas, Comanches, Cheyennes and Arapahos held a council in Indian Territory, to discuss what was to be done. They decided to make one more stand against the white hunters, especially those south of the Arkansas.

It was arranged. The Comanches had sent a peace pipe to the council; all the chiefs smoked, and agreed to peace among themselves and war against the Americans who were destroying the buffalo reserves. I-sa-tai, a Comanche medicine-man, announced that he had a medicine that would make the guns of the whites useless. Many of the Cheyennes and Apaches and others believed him.

The first point of attack should be the white hunters' camp at Adobe Walls, in the Pan-handle of northern Texas. That was the nearest camp, and was one of the most annoying.

"Those men shall not fire a shot; we shall kill them all," I-sa-tai promised. "We shall ride up to them and knock them on the head. My medicine says so."

A war party of seven hundred Red River Comanches, Southern Cheyennes, Arapahos, Kiowas and Apaches were formed, to wipe out Adobe Walls.

Quana Parker, chief of the Kwahadi band of Comanches, became the leader. The Kwahadi Comanches had not signed the treaty of 1867, by which the other tribes sold their lands and settled upon places assigned them by the Government. They continued to roam freely, and hunt where they chose. They always had been wild, independent Indians of Texas.

Chief Quana Parker himself was a young man of thirty years, but a noted warrior. Like his name, he was half Indian, half white--although all Comanche. In 1835 the Comanches had captured a small settlement in east Texas, known as Parker's Fort; had carried off little John Parker, aged six, and little Cynthia Ann Parker, aged nine. Cynthia grew up with the Comanches, and married Peta Nokoni or Wanderer, a fine young brave who was elected head chief of the Kwahadis. Their baby was named Quana, and now in 1874 was called Quana Parker.

In 1860, or when he was fifteen years old, his mother had been retaken by the Texas Rangers. She lived with her brother, Colonel Dan Parker, four years. Then she died. Boy Quana was Indian; he stayed with the Comanches. He won his chiefship by running away with a girl that he loved, whom a more wealthy warrior tried to take from him. Many young men joined him in the hills, until his rival and the girl's father were afraid of him, and the tribe elected him head chief.

The Texans feared him, if they feared any Indian; all Indians respected him; in June, this 1874, he marshalled his allied chiefs and warriors for the raid upon the buffalo hunters. He had more faith in bullets and arrows than in I-sa-tai's medicine, but I-sa-tai went along.

There were two Adobe Walls, on the south branch of the Canadian River, in Hutchinson County, Texas Pan-handle. The first had been built in 1845 by William Bent and his partners of Bent's Fort, as another trading-post, to deal with the Red River Comanches. William Bent had sent one of his clerks, named by the Cheyennes Wrinkled Neck, to build it.

After it had been abandoned, in 1864 General Kit Carson had attacked the winter villages of three thousand Comanche, Kiowa, Apache and Arapaho warriors and their families, here. He was just able to get his four hundred men safely away.

The second Adobe Walls had been built only a year or two ago. It was down-river from the old Adobe Walls, and formed a small settlement where the buffalo-hunters came in, from their outside camps, to store their hides and get supplies, and so forth. There were Hanrahan's saloon, and Rath's general store, and several sheds and shacks, mainly of adobe or dried clay, and a large horse and mule corral, of adobe and palisades, with a plank gate. Such was Adobe Walls of 1874, squatted amidst the dun bunch-grass landscape broken only by the shallow South Canadian and a rounded hill or two.

The Rath store was the principal building. It was forty feet long, and contained two rooms--the store room, and a room where persons might sleep. It looked not unlike a fort; the thick walls had bastions at the corners, the deep window casings were embrasured or sloped outward, so that guns might be aimed at an angle, from within.

In the night of June 24 twenty-eight men and one woman were at Adobe Walls. Excepting Mrs. Rath, and her husband, and Saloon-keeper Hanrahan, and two or three Mexican clerks and roustabouts, they mainly were buffalo-hunters. Billy Dixon, government scout, was in with his wagon and outfit; he expected to start for his camp, twenty-five miles south, in the morning. The Shadley brothers and their freighter outfit were here. And likewise some twenty others.

It was not to be expected that Indians would attack Adobe Walls itself; they were more likely to raid the camps: but the general store seemed to be a great prize--the Comanches and Kiowas and Apaches and Arapahos and Cheyennes counted upon plunder of clothes and flour and ammunition, and I-sa-tai's medicine had told him to try Adobe Walls first.

The night was warm. Scout Dixon slept out-doors, in his wagon; the Shadley brothers slept in their wagon; several men slept upon buffalo-robes, on the ground; others were in the Rath store and in the saloon.

Shortly after midnight the men in the saloon were awakened by the cracking of the roof ridge-pole. They were afraid that the roof might be falling, so they piled out to fix it. Their noise aroused the men in the wagons and on the ground; and all together they worked. By the time they were done, sunrise was showing in the east, and Billy Dixon thought that it was not worth while to go to bed again.

He prepared to set out for his buffalo-camp. Pretty soon he sent one of his men down to the creek bottoms, to bring in the horses. The man came running back, shouting and pointing.

"Injuns!"

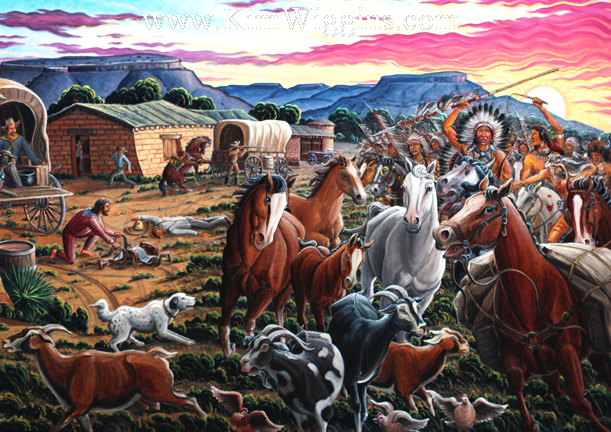

A solid line of feathered heads, sharply sketched against the reddening sky, was charging in across the bottoms, directly for the store and saloon and corral. The drum of galloping hoofs began to beat in a long roll, and a tremendous war-whoop shattered the still air.

"Look out for the horses!" Scout Dixon yelled, He tied his own saddle-horse short to the wagon and grabbed his Sharp's buffalo-gun. He thought that this was a raid for a stampede. But instead of scattering to round up the grazing stock the Indians rode straight on--in all his experience as scout and hunter they were the boldest, best-armed "bunch" that he had ever seen; and they meant business. They were here to wipe out the whole place; had warriors enough to do it, too.

From one hundred yards bullets spattered. Without waiting longer he dived for the saloon and shelter. There were six other men in the saloon, mostly jerked from slumber in all kinds of undress. Firing right and left and whooping, the Indians poured through among the buildings like a torrent; from the saloon windows the white men and Mexicans replied.

Chief Quana Parker's cavalry had high hopes. He led. Last night I-sa-tai's medicine had been strong. This morning a foolish Cheyenne had killed a skunk--a reckless thing to do, for a skunk was a medicine animal. Whether this broke the medicine, I-sa-tai did not say. They were to find out.

Had the ridge-pole not cracked and got the hunters up; or had the Indians arrived only fifteen minutes earlier, while the hunters were busy with the ridge-pole, they truly would have captured Adobe Walls and killed everybody in it. The medicine almost worked, but not quite. Just the killing of the skunk had broken it.

For a brief space the seven men in the saloon were hard beset. They appeared to be the only defenders of the settlement. The heavy sleepers in the store and the house were not yet enough awake to know what had occurred. On their rapid ponies the Indians flashed past between the saloon and Rath's, darted here and there around the corners, flung to earth and ran to pry at windows and doors.

Horses were down and kicking, in the street. An Indian scampered from the Shadley brothers' wagon, his arms full of plunder; but a bullet from the saloon dropped him like a stone. Nothing was heard from the two Shadleys; probably they were dead in their wagon.

The saloon was thick with powder-smoke; the air outside quivered to the whoops and jeers and threats. Would the store hold out? Hurrah! The boys in there were up and shouting, too. Shots spouted from the windows.

The first charge had passed on. Chief Quana reformed his ranks, for another. Abode Walls, now rudely awakened, hastily prepared. There were the seven men in the Hanrahan saloon--a low, box-like affair, sitting by itself at one side of the store; there were Store-keeper Rath and his wife, and a couple of hunters, in the Rath house, on the other side of the store; and in the long store itself there were twelve or fourteen men.

Peeping out, dazed and bootless and coatless just as they had sprung from their blankets, they saw a wonderful sight. Fully six hundred Indians were coming again, in a solid front.

The long feathered war-bonnets of the Comanches and Cheyennes flared upon the breeze; the painted, naked riders lashed and urged--"Yip! Yip! Yip!"; the ponies, of all colors, jostled and plunged, and their hoof-beats drummed; above the tossing crests bare arms upheld a fringe of shaking guns and bows and lances. Unless he had been at Beecher's Island and witnessed the charge of Roman Nose, not a man of Adobe Walls ever had seen so terrible a spectacle as this, under the pink sky of the fresh June morning.

On a hill to the right I-sa-tai the medicine-man stood, all unclothed except for a bonnet of sage twigs. He was making medicine.

The buffalo-hunters and the two or three freighters, the clerks and roustabouts and Saloon-keeper Hanrahan and Store-keeper Rath jammed their guns through every window and cranny fronting the charge, and waited. It seemed as if the red cavalry surely would ride right over the place and flatten it.

Four hundred yards, three hundred yards, two hundred yards--"Yip! Yip! Yip!" "Hi! Hi!"; the hoof-beats were thunderous; it was an avalanche; smoke puffed from the ponies' backs, bullets whined and thudded--and the guns of saloon and store and house burst into action.

They were crack shots, the most of those Adobe Walls men; had the best of rifles, and plenty of cartridges. Down lunged ponies, sending their riders sprawling; the white men's guns spoke rapidly, the noise of shot and shout and yell was deafening; the charging line broke, careering right and left and straight through. On scoured the shrieking squads, but leaving dead and wounded ponies and limping, scurrying warriors.

But this was not the end. Anybody might know that. The Adobe Walls men busied themselves; some stayed on watch, others enlarged their loop-holes or desperately knocked holes through the thick adobe, for better shooting. The windows were too few; the whole rear of the store itself was blank. The door had been battered, and now sacks of flour were piled against it, to strengthen it.

Indians, dismounted, skulked everywhere, taking pot-shots at the loop-holes, and forcing the men to keep close under cover.

Some seventy-five yards behind the store was a large stack of buffalo-hides. From the saloon Scout Billy Dixon saw an Indian pony standing beside it, and might just glimpse a Comanche head-dress, around the corner of the stack.

He aimed at the head-dress and fired. The headdress disappeared, but the Indian must have dodged to the other corner, for Rath's house opened fire on him, and he dodged back again. Scout Dixon met him with another bullet. The Indian found himself in a hot place. His pony was killed. He had to stay or run; so he stayed, and cowered out of sight, waiting for a chance to shoot or to escape.

But that would not do. He was a danger to the premises, and should be routed. Scout Dixon guessed at his location, behind the hides; drew quick bead, and let drive. The heavy ball from the Sharp's buffalo-gun--a fifty-caliber bullet, on top of one hundred and twenty grains of powder--tore clear through the stack. Out dived the Comanche, jumping like a jack-rabbit and yelping like a coyote at every leap, and gained cover in a bunch of grass.

"Bet I scorched him," Billy Dixon chuckled.

Other guns were still cracking, trying to clear the skulkers and to hold off the main body. The warriors were concealed behind buffalo-hide stacks, in sheds, and lying flat upon the prairie. The firing never slackened; there were rushes and retreats. The scene, here on the dry plains of northern Texas, reminded one of the sieges of settlers' forts in Kentucky and West Virginia one hundred years ago. The Indians were outside, the frontiersmen were inside, and no help near.

The sun rose. By this time the Indians hiding close in had been disposed of, in one way or another. They were shooting from two hundred yards--but that was a dead range for the white men's guns. The buffalo-hunters asked nothing better.

Their rifles were sighted to a hair. The hunters were accustomed to lie all day, on the buffalo range, and from their "stand" to leeward plant bullet after bullet of their Sharp's .50-120, Ballard .45-90, and Winchester .44-40 behind the buffalo's shoulders. A circle eight inches in diameter was the fatal spot--and from two hundred yards they rarely varied in their aim.

An Indian who exposed himself two hundred or three hundred yards away stood a poor show of escape.

The Chief Quana men soon learned this. They already knew it, from other fights, upon the buffalo range itself. They had grown to respect a buffalo-hunter at bay.

Now they withdrew, by squads, to six hundred, seven hundred, eight hundred yards; and firing wildly they sought to cover the retreat of their wounded and their warriors afoot. The Indians between the main party and the fort would spring up, run a few steps, and drop again before a bullet caught them.

Thus the fight lasted until the middle of the afternoon. The hunters inside the walls had no rest, but they ventured to move about a little. The men in the saloon bolted out, and ran into the store. From here Scout Dixon, scanning the country, saw a moving object at the base of the hill, eight hundred yards distant. The Indians now were mostly out of sight, beyond. He commenced shooting at the tiny mark, correcting his aim by the dust thrown up when the bullets landed. The old single-shot Sharp's, either fifty caliber or the forty-four sharp-shooter Creedmore pattern fitted with special sights, was the favorite gun of the buffalo-hunters. Scout Dixon kept elevating his rear sight, and pumping away. Finally he thought that he had hit the mark; it did not move. After the battle and siege he rode over there, to see. He had shot an Indian through the breast, with a fifty-caliber ball at eight hundred yards.

Toward evening the Indians stopped fighting. I-sa-tai's medicine had proved weak, for the hunters' guns seemed to be as bad as ever. But the battle was not yet ended, as Adobe Walls found out, the next morning. There were charges again; guns grew hot, the smoke thickened, the Indians were everywhere around, determined to force the doors and windows. The hearts and hands of the twenty-five able-bodied men never faltered.

On the evening of the third day the siege was lifted; for with the fourth morning no Indians were to be seen. All about, on the grassy plain between the town and the hills, dead ponies were scattered; the walls of the buildings were furrowed by bullets; rude loopholes gaped; and in the little street the dust was dyed red.

The two Shadley brothers had been killed, in their wagon; William Tyler, a camp hand, had been killed before he reached shelter. But the twenty-five others, and the brave woman, had stood off the flower of the allied Comanche, Kiowa, Arapaho, Apache and Southern Cheyenne nations.

How many Indians had been killed nobody knew. Nine were found among the buildings and within one hundred yards; four more were discovered, at longer range; in the hills the signs showed that the loss had been at least thirty or thirty-five.

Early in the morning, while Adobe Walls was busy looking about, a lone buffalo-hunter ambled in. He was George Bellman, a German whose camp lay only eight miles up the Canadian; here he lived alone--he had not heard the shooting nor seen a single Indian, and the ponies strewn over the prairie much astonished him.

"Vat kind a disease iss der matter mit de hosses, hey?" he asked, curiously.

"Died of lead poison," answered Cranky McCabe.

The heads of twelve of the Indians were cut off and stuck up on the pickets and posts of the corral; were left there, to dry in the sun, for a hideous warning. But the buffalo-hunters decided to hunt no more, this season. The Pan-handle country was getting "unhealthy!"

So much had Chief Quana and his brother chiefs and warriors achieved. They had spoiled the buffalo hunting. After a short time many of the Arapahos and Kiowas and Apaches hurried back to their reservation in Indian Territory. The Cheyennes and others raided north, through western Kansas and eastern Colorado. The Chief Quana Comanches went south, to their own range. He and his Kwahadis or Antelope Eaters stayed out on their Staked Plain for two years; they were the last to quit. Then he accepted peace; he saw that it was no use to fight longer. Moreover, he became one of the best, most civilized Indians in all the West.

For his Comanches he chose lands at the base of the Wichita Mountains near Fort Sill in southwestern Oklahoma. He built himself a large two-story house, well painted and furnished; he lived like a rich rancher, and owned thousands of acres of farm and thousands of cattle; he wore the finest of white-man's clothes, or the finest of chief's clothes as suited him; he was still living there, in 1910, and no man was more highly respected. He rode in the parade at Washington when Theodore Roosevelt was inaugurated President. President Roosevelt paid him a return visit, for a wolf hunt.

But the old-time buffalo-hunters who were in Adobe Walls on June 24, 1874, never have forgotten that charge by the Quana Parker fierce cavalry.