Out of the antagonistic and contending factions mentioned in the last two chapters, the bogus Legislature and its Border-Ruffian adherents on the one hand, and the framers and supporters of the Topeka Constitution on the other, grew the civil war in Kansas. The bogus Legislature numbered thirty-six members.

These had only received, all told, 619 legal bond fide Kansas votes; but, what answered their purposes just as well, 4408 Missourians had cast their ballots for them, making their total constituency (if by discarding the idea of a State line we use the word in a somewhat strained sense) 5427. This was at the March election, 1855. Of the remaining 2286 actual Kansas voters disclosed by Seeder's census, only 791 cast their ballots. That summer's emigration, however, being mainly from the free States, greatly changed the relative strength of the two parties. At the election of October 1, 1855, in which the free-State men took no part, Whitfield, for delegate, received 2721 votes, Border Ruffians included. At the election for members of the Topeka Constitutional Convention, a week later, from which the pro-slavery men abstained, the free-State men cast 2710 votes, while Reeder, their nominee for delegate, received 2849. For general service, therefore, requiring no special effort, the numerical strength of the factions was about equal; while on extraordinary occasions the two thousand Border-Ruffian reserve lying a little farther back from the State line could at any time easily turn the scale. The free-State men had only their convictions, their intelligence, their courage, and the moral support of the North; the conspiracy had its secret combination, the territorial officials, the Legislature, the bogus laws, the courts, the militia officers, the President, and the army. This was a formidable array of advantages; slavery was playing with loaded dice.

With such a radical opposition of sentiment, both factions were on the alert to seize every available vantage ground. The bogus laws having been enacted, and the free-State men having, at the Big Springs Convention, resolved on the failure of peaceable remedies to resist them to a "bloody issue," the conspiracy was not slow to cover itself and its projects with the sacred mantle of authority. Opportunely for them, about this time Governor Shannon, appointed to succeed Reeder, arrived in the Territory. Coming by way of the Missouri River towns, he fell first among Border-Ruffian companionship and influences; and perhaps having his inclinations already molded by his Washington instructions, his early impressions were decidedly adverse to the free-State cause. His reception speech at Westport, in which he maintained the legality of the Legislature, and his determination to enforce their laws, delighted his pro-slavery auditors. To further enlist his zeal in their behalf, a few weeks later they formally organized a "law-and-order party" by a large public meeting held at Leavenworth. All the territorial dignitaries were present; Governor Shannon presided; John Calhoun, the Surveyor-General, made the principal speech, a denunciation of the "abolitionists" supporting the Topeka movement; Chief-Justice Lecompte dignified the occasion with approving remarks. With public opinion propitiated in advance, and the Governor of the Territory thus publicly committed to their party, the conspirators felt themselves ready to enter upon the active campaign to crush out opposition, for which they had made such elaborate preparations.

Faithful to their legislative declaration they knew but one issue, slavery. All dissent, all non-compliance, all hesitation, all mere silence even, were in their stronghold towns, like Leavenworth, branded as "abolitionism," declared to be hostility to the public welfare, and punished with proscription, personal violence, expulsion, and frequently death. Of the lynchings, the mobs, and the murders, it would be impossible, except in a very extended work, to note the frequent and atrocious details. The present chapters can only touch upon the more salient movements of the civil war in Kansas, which happily were not sanguinary; if, however, the individual and more isolated cases of bloodshed could be described, they would show a startling aggregate of barbarity and loss of life for opinion's sake. Some of these revolting crimes, though comparatively few in number, were committed, generally in a spirit of lawless retaliation, by free-State men.

Among other instrumentalities for executing the bogus laws, the bogus Legislature had appointed one Samuel J. Jones sheriff of Douglas County, Kansas Territory, although that individual was at the time of his appointment, and long afterwards, United States postmaster of the town of Westport, Missouri. Why this Missouri citizen and Federal official should in addition be clothed with a foreign territorial shrievalty of a county lying forty or fifty miles from his home is a mystery which was never explained outside a Missouri Blue Lodge.

A few days after the "law-and-order" meeting in Leavenworth, there occurred a murder in a small settlement thirteen miles west of the town of Lawrence. The murderer, a pro-slavery man, first fled, to Missouri, but returned to Shawnee Mission and sought the official protection of Sheriff Jones; no warrant, no examination, no commitment followed, and the criminal remained at large. Out of this incident, the officious sheriff managed most ingeniously to create an embroilment with the town of Lawrence, Buckley, who was alleged to have been accessory to the crime, obtained a peace-warrant against Branson, a neighbor of the victim. With this peace warrant in his pocket, but without showing or reading it to his prisoner, Sheriff Jones and a posse of twenty-five Border Ruffians proceeded to Branson's house at midnight and arrested him. Alarm being given, Branson's free-State neighbors, already exasperated at the murder, rose under the sudden instinct of self-protection and rescued Branson from the sheriff and his posse that same night, though without other violence than harsh words.

Burning with the thirst of personal revenge, Sheriff Jones now accused the town of Lawrence of the violation of law involved in this rescue, though the people of Lawrence immediately and earnestly disavowed the act. But for Sheriff Jones and his superiors the pretext was all-sufficient. A Border-Ruffian foray against the town was hastily organized. The murder occurred November 21; the rescue November 26. November 27, upon the brief report of Sheriff Jones, demanding a force of three thousand men "to carry out the laws," Governor Shannon issued his order to the two major-generals of the skeleton militia, "to collect together as large a force as you can in your division, and repair without delay to Lecompton, and report yourself to S. J. Jones, sheriff of Douglas County." [Footnote: Governor Shannon, order to Richardson, November 27, 1855. Same order to Strickler, same date. Senate Executive Documents, 3d Sess. 34th Cong., Vol. II., p. 53.] The Kansas militia was a myth; but the Border Ruffians, with their backwoods rifles and shotguns, were a ready resource. To these an urgent appeal for help was made; and the leaders of the conspiracy in prompt obedience placarded the frontier with inflammatory handbills, and collected and equipped companies, and hurried them forward to the rendezvous without a moment's delay. The United States Arsenal at Liberty, Missouri, was broken into and stripped of its contents to supply cannon, small arms, and ammunition. In two days after notice a company of fifty Missourians made the first camp on Wakarusa Creek, near Franklin, four miles from Lawrence. In three or four days more an irregular army of fifteen hundred men, claiming to be the sheriff's posse, was within striking distance of the town. Three or four hundred of these were nominal residents of the Territory; [Footnote: Shannon, dispatch, December 11, 1855, to President Pierce. Senate Ex. Doc., 3d Sess. 34th Cong., Vol. II., p. 63.] all the remainder were citizens of Missouri. They were not only well armed and supplied, but wrought up to the highest pitch of partisan excitement. While the Governor's proclamation spoke of serving writs, the notices of the conspirators sounded the note of the real contest. "Now is the time to show game, and if we are defeated this time, the Territory is lost to the South," said the leaders. There was no doubt of the earnestness of their purpose. Ex-Vice-President Atchison came in person, leading a battalion of two hundred Platte County riflemen.

News of this proceeding reached the people of Lawrence little by little, and finally, becoming alarmed, they began to improvise means of defense. Two abortive imitations of the Missouri Blue Lodges, set on foot during the summer by the free-State men, provoked by the election invasion in March, furnished them a starting-point for military organization. A committee of safety, hurriedly instituted, sent a call for help from Lawrence to other points in the Territory, "for the purpose of defending it from threatened invasion by armed men now quartered in its vicinity." Several hundred free-State men promptly responded to the summons. The Free-State Hotel served as barracks. Governor Robinson and Colonel Lane were appointed to command. Four or five small redoubts, connected by rifle-pits, were hastily thrown up; and by a clever artifice they succeeded in bringing a twelve-pound brass howitzer from its storage at Kansas City. Meantime the committee of safety, earnestly denying any wrongful act or purpose, sent an urgent appeal for protection to the commander of the United States forces at Fort Leavenworth, another to Congress, and a third to President Pierce.

Amid all this warlike preparation to keep the peace, no very strict military discipline could be immediately enforced. The people of Lawrence, without any great difficulty, obtained daily information concerning the hostile camps. They, on the other hand, professing no purpose but that of defense and self-protection were obliged to permit free and constant ingress to their beleaguered town. Sheriff Jones made several visits unmolested on their part, and without any display of writs or demand for the surrender of alleged offenders on his own. One of the rescuers even accosted him, conversed with him, and invited him to dinner. These free visits had the good effect to restrain imprudence and impulsiveness on both sides. They could see that a conflict meant serious results. With the advantage of its defensive position, Lawrence was as strong as the sheriff's mob. On one point especially the Border Ruffians had a wholesome dread. Yankee ingenuity had invented a new kind of breech-loading gun called "Sharps rifle." It was, in fact, the best weapon of its day. The free-State volunteers had some months before obtained a partial supply of them from the East, and their range, rapidity, and effectiveness had been not only duly set forth but highly exaggerated by many marvelous stories throughout the Territory and along the border. The Missouri backwoods-men manifested an almost incredible interest in this wonderful gun. They might be deaf to the "equalities" proclaimed in the Declaration of Independence or blind to the moral sin of slavery, but they comprehended a rifle which could be fired ten times a minute and kill a man at a thousand yards.

The arrivals from Missouri finally slackened and ceased. The irregular Border-Ruffian squads were hastily incorporated into the skeleton "Kansas militia." The "posse" became some two thousand strong, and the defenders of Lawrence perhaps one thousand.

Meanwhile, a sober second thought had come to Governor Shannon. To retrieve somewhat the precipitancy of his militia orders and proclamations, he wrote to Sheriff Jones, December 2, to make no arrests or movements unless by his direction. The firm defensive attitude of the people of Lawrence had produced its effect. The leaders of the conspiracy became distrustful of their power to crush the town. One of his militia generals suggested that the Governor should require the "outlaws at Lawrence and elsewhere" to surrender the Sharps rifles; another wrote asking him to call out the Government troops at Fort Leavenworth. The Governor, on his part, becoming doubtful of the legality of employing Missouri militia to enforce Kansas laws, was also eager to secure the help of Federal troops. Sheriff Jones began to grow importunate. In the Missouri camp while the leaders became alarmed the men grew insubordinate. "I have reason to believe," wrote one of their prominent men, "that before tomorrow morning the black flag will be hoisted, when nine out of ten will rally round it, and march without orders upon Lawrence. The forces of the Lecompton camp fully understand the plot and will fight under the same banner."

After careful deliberation Colonel Sumner, commanding the United States troops at Fort Leavenworth, declined to interfere without explicit orders from the War Department. These failing to arrive in time, the Governor was obliged to face his own dilemma. He hastened to Lawrence, which now invoked his protection. He directed his militia generals to repress disorder and check any attack on the town. Interviews were held with the free-State commanders, and the situation was fully discussed. A compromise was agreed upon, and a formal treaty written out and signed. The affair was pronounced to be a "misunderstanding"; the Lawrence party disavowed the Branson rescue, denied any previous, present, or prospective organization for resistance, and under sundry provisos agreed to aid in the execution of "the laws" when called upon by "proper authority." Like all compromises, the agreement was half necessity, half trick. Neither party was willing to yield honestly nor ready to fight manfully. The free-State men shrank from forcible resistance to even bogus laws. The Missouri cabal, on the other hand, having three of their best men constantly at the Governor's side, were compelled to recognize their lack of justification. They did not dare to ignore upon what a ridiculously shadowy pretext the Branson peace-warrant had grown into an army of two thousand men, and how, under the manipulation of Sheriff Jones, a questionable affidavit of a pro-slavery criminal had been expanded into the _casus belli_ of a free-State town. They consented to a compromise "to cover a retreat."

When Governor Shannon announced that the difficulties were settled, the people of Lawrence were suspicious of their leaders, and John Brown manifested his readiness to head a revolt. But his attempted speech was hushed down, and the assurance of Robinson and Lane that they had made no dishonorable concession finally quieted their followers. There were similar murmurs in the pro-slavery camps. The Governor was denounced as a traitor, and Sheriff Jones declared that "he would have wiped out Lawrence." Atchison, on the contrary, sustained the bargain, explaining that to attack Lawrence under the circumstances would ruin the Democratic cause. "But," he added with a significant oath, "boys, we will fight some time!" Thirteen of the captains in the Wakarusa camp were called together, and the situation was duly explained. The treaty was accepted, though the Governor confessed "there was a silent dissatisfaction" at the result. He ordered the forces to disband; prisoners were liberated, and with the opportune aid of a furious rainstorm the Border-Ruffian army gradually melted away. Nevertheless, the "Wakarusa War" left one bitter sting to rankle in the hearts of the defenders of Lawrence, a free-State man having been killed by a pro-slavery scouting party.

The truce patched up by this Lawrence treaty was of comparatively short duration. The excitement which had reigned in Kansas during the whole summer of 1855, first about the enactments of the Bogus Legislature, and then in regard to the formation of the Topeka Constitution, was now extended to the American Congress, where it raged for two long months over the election of Speaker Banks. In Kansas, during the same period, the vote of the free-State men upon the Topeka Constitution and the election for free-State officers under it kept the Territory in a ferment. During and after the contest over the speakership at Washington, each State Legislature became a forum of Kansas debate. The general public interest in the controversy was shown by discussions carried on by press, pulpit, and in the daily conversation and comment of the people of the Union in every town, hamlet, and neighborhood. No sooner did the spring weather of 1856 permit, than men, money, arms, and supplies were poured into the Territory of Kansas from the North.

In the Southern States also this propagandism was active, and a number of guerrilla leaders with followers recruited in the South, and armed and sustained by Southern contributions and appropriations, found their way to Kansas in response to urgent appeals of the Border chiefs. Buford, of Alabama; Titus, of Florida; Wilkes, of Virginia; Hampton, of Kentucky; Treadwell, of South Carolina, and others, brought not only enthusiastic leadership but substantial assistance. Both the factions which had come so near to actual battle in the "Wakarusa war," though nominally disbanded, in reality, continued their military organizations,--the free-State men through apprehension of danger, the Border Ruffians because of their purpose to crush out opposition. Strengthened on both sides with men, money, arms, and supplies, the contest was gradually resumed with the opening spring.

The vague and double-meaning phrases of the Lawrence agreement furnished the earliest causes of a renewal of the quarrel. "Did you not pledge yourselves to assist me as sheriff in the arrest of any person against whom I might have a writ?" asked Sheriff Jones of Robinson and Lane in a curt note. "We may have said that we would assist any proper officer in the service of any legal process," they replied, standing upon their interpretation. This was, of course, the original controversy--slavery burning to enforce her usurpation, freedom determined to defend her birthright. Sheriff Jones had his pockets always full of writs issued in the spirit of persecution but was often baffled by the sharp wits and ready resources of the free-State people, and sometimes defied outright. Little by little, however, the latter became hemmed and bound in the meshes of the various devices and proceedings which the territorial officials evolved from the bogus laws. President Pierce, in his special message of January 24, declared what had been done by the Topeka movement to be "of a revolutionary character" which would "become treasonable insurrection if it reach the length of organized resistance."

Following this came his proclamation of February 11, leveled against "combinations formed to resist the execution of the territorial laws." Early in May, Chief-Justice Lecompte held a term of his court, during which he delivered to the grand jury his famous instructions on constructive treason. Indictments were found, writs issued, and the principal free-State leaders arrested or forced to flee from the Territory. Governor Robinson was arrested without warrant on the Missouri River, and brought back to be held in military custody till September. [Transcriber's Note: Lengthy footnote relocated to chapter end.] Lane went East and recruited additional help for the contest. Meanwhile Sheriff Jones, sitting in his tent at night, in the town of Lawrence, had been wounded by a rifle or pistol in the attempt of some unknown person to assassinate him. The people of Lawrence denounced the deed; but the sheriff hoarded up the score for future revenge. One additional incident served to precipitate the crisis. The House of Representatives at Washington, presided over by Speaker Banks, and under control of the opposition, sent an investigating committee to Kansas, consisting of Wm. A. Howard, of Michigan, John Sherman, [Footnote: Owing to the illness of Mr. Howard, chairman of the committee, the long and elaborate majority report of this committee was written by John Sherman. Its methodical analysis and powerful presentation of evidence made it one of the most popular and convincing documents ever issued.] of Ohio, and Mordecai Oliver, of Missouri, which, by the examination of numerous witnesses, was probing the Border-Ruffian invasions, the illegality of the bogus Legislature, and the enormity of the bogus laws to the bottom.

Ex-Governor Reeder was in attendance on this committee, supplying data, pointing out from personal knowledge sources of information, cross-examining witnesses to elicit the hidden truth. To embarrass this damaging exposure, Judge Lecompte issued a writ against the ex-Governor on a frivolous charge of contempt. Claiming but not receiving exemption from the committee, Beeder on his personal responsibility refused to permit the deputy marshal to arrest him. The incident was not violent, nor even dramatic. No posse was summoned, no further effort made, and Reeder, fearing personal violence, soon fled in disguise. But the affair was magnified as a crowning proof that the free-State men were insurrectionists and outlaws.

It must be noted in passing that by this time the Territory had by insensible degrees drifted into the condition of civil war. Both parties were zealous, vigilant, and denunciatory. In nearly every settlement suspicion led to combination for defense, combination to some form of oppression or insult, and so on by easy transition to arrest and concealment, attack and reprisal, expulsion, theft, house-burning, capture, and murder. From these, again, sprang barricaded and fortified dwellings, camps and scouting parties, finally culminating in roving guerrilla bands, half partisan, half predatory. Their distinctive characters, however, display one broad and unfailing difference. The free-State men clung to their prairie towns and prairie ravines with all the obstinacy and courage of true defenders of their homes and firesides. The pro-slavery parties, unmistakable aliens and invaders, always came from, or retired across, the Missouri line. Organized and sustained in the beginning by voluntary contributions from that and distant States, they ended by levying forced contributions, by "pressing" horses, food, or arms from any neighborhood they chanced to visit. Their assumed character changed with their changing opportunities or necessities. They were squads of Kansas militia, companies of "peaceful emigrants," or gangs of irresponsible outlaws, to suit the chance, the whim, or the need of the moment.

Since the unsatisfactory termination of the "Wakarusa war," certain leaders of the conspiracy had never given up their project of punishing the town of Lawrence. A propitious moment for carrying it out seemed now to have arrived. The free-State officers and leaders were, thanks to Judge Lecompte's doctrine of constructive treason, under indictment, arrest, or in flight; the settlers were busy with their spring crops; while the pro-slavery guerrillas, freshly arrived and full of zeal, were eager for service and distinction. The former campaign against the town had failed for want of justification; they now sought a pretext which would not shame their assumed character as defenders of law and order. In the shooting of Sheriff Jones in Lawrence, and in the refusal of ex-Governor Beeder to allow the deputy-marshal to arrest him, they discovered grave offenses against the territorial and United States laws. Determined also no longer to trust Governor Shannon, lest he might again make peace, United States Marshal Donaldson issued a proclamation on his own responsibility, on May 11, 1856, commanding "law-abiding citizens of the Territory" "to be and appear at Lecompton, as soon as practicable and in numbers sufficient for the proper execution of the law." Moving with the promptness and celerity of preconcerted plans, ex-Vice-President Atchison, with his Platte County Rifles and two brass cannon, the Kickapoo Rangers from Leavenworth and Weston, Wilkes, Titus, Buford, and all the rest of the free lances in the Territory, began to concentrate against Lawrence, giving the marshal in a very few days a "posse" of from 500 to 800 men, armed for the greater part with United States muskets, some stolen from the Liberty arsenal on their former raid, others distributed to them as Kansas militia by the territorial officers. The Governor refused to interfere to protect the threatened town, though an urgent appeal to do so was made to him by its citizens, who after stormy and divided councils resolved on a policy of non-resistance.

They next made application to the marshal, who tauntingly replied that he could not rely on their pledges, and must take the liberty to execute his process in his own time and manner. The help of Colonel Sumner, commanding the United States troops, was finally invoked, but his instructions only permitted him to act at the call of the Governor or marshal. [Footnote: Sumner to Shannon, May 12, 1856. Senate Ex. Doc., No. 10, 3d Sess. 34th Cong. Vol. V., p. 7.] Private persons who had leased the Free-State Hotel vainly besought the various authorities to prevent the destruction of their property. Ten days were consumed in these negotiations; but the spirit of vengeance refused to yield. When the citizens of Lawrence rose on the 21st of May they beheld their town invested by a formidable military force.

During the forenoon the deputy-marshal rode leisurely into the town attended by less than a dozen men, being neither molested nor opposed. He summoned half a dozen citizens to join his posse, who followed, obeyed, and assisted him. He continued his pretended search and, to give color to his errand, made two arrests. The Free-State Hotel, a stone building in dimensions fifty by seventy feet, three stories high and handsomely furnished, previously occupied only for lodging-rooms, on that day for the first time opened its table accommodations to the public, and provided a free dinner in honor of the occasion. The marshal and his posse, including Sheriff Jones, went among other invited guests and enjoyed the proffered hospitality. As he had promised to protect the hotel, the reassured citizens began to laugh at their own fears. To their sorrow they were soon undeceived. The military force, partly rabble, partly organized, had meanwhile moved into the town.

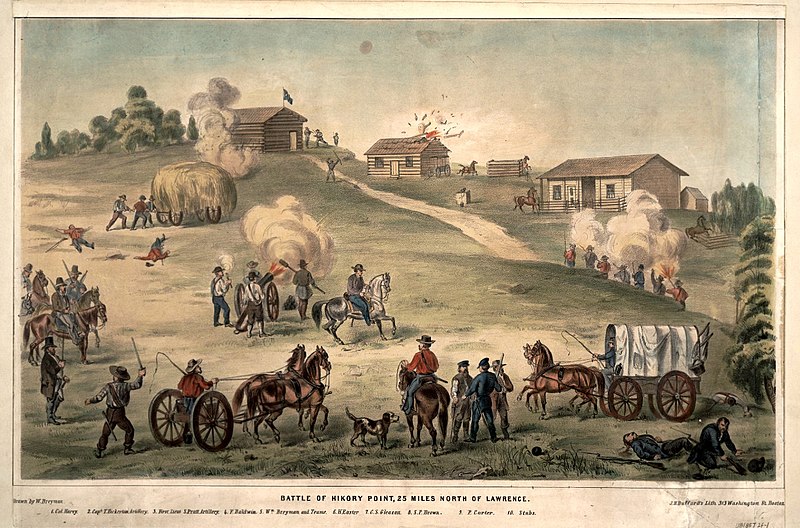

To save his official skirts from stain, the deputy-marshal now went through the farce of dismissing his entire posse of citizens and Border Ruffians, at which juncture Sheriff Jones made his appearance, claiming the "posse" as his own. He planted a company before the hotel, and demanded a surrender of the arms belonging to the free-State military companies. Refusal or resistance being out of the question, half a dozen small cannon were solemnly dug up from their concealment and, together with a few Sharps rifles, formally delivered. Half an hour later, turning a deaf ear to all remonstrance, he gave the proprietors until 5 o'clock to remove their families and personal property from the Free-State Hotel. Atchison, who had been haranguing the mob, planted his two guns before the building and trained them upon it. The inmates being removed, at the appointed hour a few cannon balls were fired through the stone walls. This mode of destruction being slow and undramatic, and an attempt to blow it up with gunpowder having proved equally unsatisfactory, the torch was applied, and the structure given to the flames. [Footnote: Memorial, Senate Executive Document, 3d Session 34th Congress. Volume II, pp. 73-85.] Other squads had during the same time been sent to the several printing-offices, where they broke the presses, scattered the type, and demolished the furniture. The house of Governor Robinson was also robbed and burned. Very soon the mob was beyond all control, and spreading itself over the town engaged in pillage till the darkness of night arrested it. Meanwhile the chiefs sat on their horses and viewed the work of destruction.

If we would believe the chief actors, this was the "law and order party," executing the mandates of justice. Part and parcel of the affair was the pretense that this exploit of prairie buccaneering had been authorized by Judge Leeompte's court, the officials citing in their defense a presentment of his grand jury, declaring the free-State newspapers seditious publications, and the Free-State Hotel a rebellious fortification, and recommending their _abatement_ as nuisances. The travesty of American government involved in the transaction is too serious for ridicule. In this incident, contrasting the creative and the destructive spirit of the factions, the Emigrant Aid Society of Massachusetts finds its most honorable and triumphant vindication. The whole proceeding was so childish, the miserable plot so transparent, the outrage so gross, as to bring disgust to the better class of Border Ruffians who were witnesses and accessories. The free-State men have recorded the honorable conduct of Colonel Zadock Jackson, of Georgia, and Colonel Jefferson Buford, of Alabama, as well as of the prosecuting attorney of the county, each of whom denounced the proceedings on the spot.

[Relocated Footnote: Governor Robinson being on his way East, the steamboat on which he was traveling stopped at Lexington, Missouri. An unauthorized mob induced the Governor, with that persuasiveness in which the Border Ruffians had become adepts, to leave the boat, detaining him at Lexington on the accusation that he was fleeing from an indictment. In a few days an officer came with a requisition from Governor Shannon, and took the prisoner by land to Westport, and afterwards from there to Kansas City and Leavenworth. Here he was placed in the custody of Captain Martin, of the Kickapoo Rangers, who proved a kind jailer, and materially assisted in protecting him from the dangerous intentions of the mob which at that time held Leavenworth under a reign of terror.

Mrs. Robinson, who has kindly sent us a sketch of the incident, writes: "On the night of the 28th [of May] for greater security General Richardson of the militia slept in the same bed with the prisoner, while Judge Lecompte and Marshal Donaldson slept just outside of the door of the prisoner's room. Captain Martin said: 'I shall give you a pistol to help protect yourself if worse comes to worst!' In the early morning of the next day, May 29, a company of dragoons with one empty saddle came down from the fort, and while the pro-slavery men still slept, the prisoner and his escort were on their way across the prairies to Lecompton in the charge of officers of the United States Army. The Governor and other prisoners were kept on the prairie near Lecompton until the 10th of September, 1856, when all were released."]