A Pen Sketch Of Sol. Rees, As Taken From The Man's Lips By The Author, Who First Met Him In The Panhandle Of Texas, In 1876.

"I was born in Delaware County, Indiana, on the 21st day of October, 1847. I enlisted in Co. E., 147th Indiana Regiment, March 5th, 1865. But as that greatest of modern wars was near its close, I did not even see the big end of the last of it. I came to Kansas in 1866, stopping for a time in the old Delaware Indian Reserve, southwest of Fort Leavenworth. From among the Delawares I went out to northwest Kansas, in 1872, and took up a claim on the Prairie Dog, in Decatur county. I trapped, and hunted buffalo, until the Indians stole my stock, when I had to quit hunting long enough to get even, and a little ahead, of the red-skins. In summer-time I would put in my time improving my homestead; in winter, hunting and trapping. But when Kansas passed her drastic "hunting law," concerning the buffalo-hide hunters, I drifted to the Panhandle of Texas, in 1876 (after taking in the Philadelphia Centennial); for the next three and one-half years you have had a pretty good trail of me."

To digress for the moment. This Sol. Rees was one of the Government scouts and guides in what is known as the "Dull Knife War" of 1878. Dull Knife was chief of a large band of northern Cheyenne warlike Indians.

Congress had passed an act moving all of the troublesome Indians from the so-called Cheyenne country north to the Indian Territory. Dull Knife and his band were taken to the Indian Territory, to near Fort Reno, on the North Fork of the Canadian river. Totally dissatisfied with the conditions as had been represented to him by the United States commissioners, he asked for, and was granted, a council. Robert Bent, a son of old Col. Bent, was a half-breed southern Cheyenne, and was the interpreter.

After the council was in sitting, Dull Knife arose and cited his wrongs. It has been said no more eloquence has ever come from the lips of an Indian orator. He said in brief: "I am going back to where my children were born; where my father and mother are buried according to Indian rites; where my forefathers followed the chase; where the snow-waters from the mountains run clear toward the white man's sea; yes, where the speckled trout leaps the swift-running waters. You people have _lied_ to us. Here your streams run slow and sluggish; the water is not good; our children sicken and die. My young warriors have been out for nearly two moons, and find no buffalo; you said there were plenty; they find only the skeletons; the white hunters have killed them for their hides. Take us back to the land of our fathers. I am done."

At this, Little Robe, head chief of the southern Cheyennes, knocked him down with a loaded quirt-handle. After regaining his feet, he shook the dust from his blanket, then, folding it around himself, walked out of the council lodge and said: "_I am going_;" and go he did.

Robert Bent said: "Little Robe, you have made a mistake." That same night his band was surrounded at their camp, by what effective troops there were at the fort; but, regardless of that, the band slipped past the cordon, Dull Knife at their lead, and for 800 miles, he whipped, eluded, and out-strategied the U. S. Army, and left a bloody trail of murder and rapine equal in atrocity to any in the annals of Indian warfare.

The author was on Gageby creek, in the Panhandle of Texas, twelve miles from Fort Elliott, sleeping soundly at midnight, when a runner came from Major Bankhead, in command, requesting me to report to him at once. And for two months I was in the saddle, but never north of the Arkansas river. I had lost track of Rees, early in the spring before the outbreak. Nor did I see or hear from him until the spring of 1907, only to find that he too had served as scout and guide on the Dull Knife raid. I here copy two official documents, now in Rees's possession, given him at that time.

OFFICE ACTING ASST. QUARTERMASTER, U. S. A., FORT WALLACE, KANSAS, NOV. 4, 1878.

Sol. Rees, Citizen Scout, has this day presented to me a certificate, given him by Major Mock, Fourth U. S. Cavalry, for thirty-nine days' service as scout and guide, at $5 per day, amounting to one hundred and ninety-five dollars. This certificate I have forwarded to Department Headquarters, asking authority and funds to pay Rees's claim. On a favorable reply and funds being furnished, I will pay the claim.

GEORGE M. LOVE, _1st Lieut. 16th Inf., Acting Asst. Q. M._

OFFICE ACTING ASST. Q. M., U. S. A., FORT WALLACE, KANSAS, NOV. 26, 1878.

_Mr. Sol. Rees, Slab City, Kan._—SIR: Enclosed please find my check, No. 59, on First National Bank of Leavenworth, Kansas, for $195, in payment for your services as scout and guide, in October and November, 1878, and for which you signed Receipt Rolls, on your being discharged. On this coming to hand, please acknowledge receipt.

I am, sir, very respectfully,

Your obedient servant,

GEORGE M. LOVE, _1st Lieut. 16th Inf., Acting A. Q. M._

* * * * *

The author now gives Rees's experiences and his observations as to the part he took in it. This is as he dictated it to the author:

I was in Kirwin, Kansas, when I heard of the runaways. It was on the 29th day of September, and anticipating the route they would follow to the Platte river, on account of water, I made a night ride, and got home just at daylight. I met settlers the next morning, and they told me the Indians had camped that night on the Prairie Dog, nine miles above my home. I saddled up and struck that way. When I got about five miles, I met a party of homeseekers, who were bringing in a wounded man toward my place. I went on, and after a while I found the Indians had gone to the Sappa. I then went to Oberlin, found the people badly excited, and there I organized a party.

Poorly armed as they were, I started on the trail. We went from there to Jake Kieffer's ranch. There the wounded began to come in, and the people that got away from the Indians. Here we reorganized and I was elected captain. Then we took the trail of the Indians, and just as we got up the divide, we saw three Indians rise up out of a draw,—man, woman, and boy about sixteen years old. We headed them off to keep them from joining the main band, and drove them to the timber on the Sappa. Here we separated into three parties, one to go above, another below, and the other to scare them out of the brush. The party I was with, when we came to the brush, did not want to go in close. So I saw it was up to me alone. I saw a squaw going up a little divide. I shot twice at her. Then I saw the buck slide down off of a bank and run into the brush, a patch of willows. I got on my horse and rode toward the willows. He rose up and shot at me. I was not more than twenty steps from him. I had been leaning over on the right side of my horse, at the time he shot. I wished to expose as little of my body as possible. I rose up and shot at him. We took shot about for five shots, when in trying to work the cylinder of my revolver, the last cartridge had slipped back, and the cylinder would not work. The warrior had fired his last shot, but I did not know it at the time.

I then went back to a man named Ingalls, and got a Colt's repeating rifle. When I came back to where I had left the Indian, he was gone. He had crossed the Sappa on a drift; and I can't, for the life of me, see how he could have done it. I dismounted and followed over, and found he was soon to be a good Injun. Taking out my knife, he signed to me, "not to scalp him until he was dead," but I had no time to spare; for there was much to do—it seemed to be a busy time of the year. So I took his scalp. I opened his shirt and found four bullet-holes in his chest, that you could cover with the palm of your hand.

After this we started back down the creek, and had gone only a short distance when we met Major Mock, with five companies of the Fourth U. S. Cavalry and two companies of the Nineteenth Infantry. The troops were all angry. Col. Lewis had been killed the day before. Here is where I met our old friend Hi. Bickerdyke. As soon as I met him, he said: "Major, here is my old friend Sol. Rees, one of the hottest Indian trailers I ever met. I have been with him in Texas in tight places."

The major said, "Glad to see you, Rees. Will you go with us as scout and guide at $5 per day and rations, until this thing is ended? I understand you are an old northern Kansas buffalo hunter, and know the country well." I said: "Yes, Major, I'll go; but not so much for the five dollars as to have this thing settled, once for all, so that we settlers can develop our homes in peace." We struck the trail on a divide. "Take the lead, Rees, everyone will follow you," he said. We followed the trail down on the Beaver; and there we got into a mess. We found where the Indians had butchered four men. They had been digging potatoes and had been literally hacked to pieces by the hoes they were using in their work. They were the old-fashioned, heavy "nigger" hoes, as they had been called in slavery days. Evidently, this had been done by squaws and small boys, for all of the moccasin-tracks indicated it. The hogpen had been opened, so that the hogs could eat the bodies. We did not have time to give the unfortunates decent burial, so the major ordered the soldiers to build a strong rail pen around the mutilated bodies, and we passed on rapidly, fearing the devils would do even worse; and the idea now was to crowd them.

From here the trail went up a divide. I said to Hi. Bickerdyke, "You take the left, I'll take the right, and Amos will lead the command up the divide." I had gone about a mile when I saw something moving toward a jut in the draw. I rode fast, and when I got up close instead of going around, as is usual in such cases, I rode straight to the object. It proved to be a white girl about sixteen years old. She was nude, her neck and shoulders were lacerated with quirt (whip) marks. She was badly frightened and threw up her hands in an appealing way. I said: "Poor girl! Have they shot you?"

She answered: "No; but I suffer so with pain and fright."

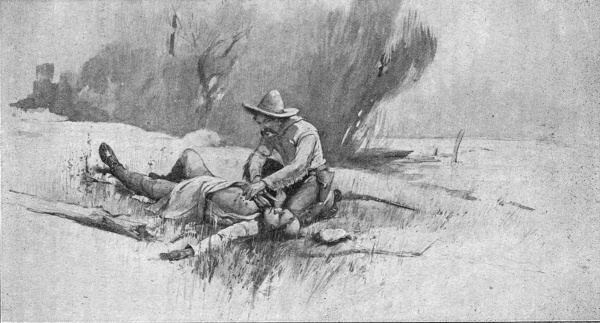

She was of foreign origin. It was hard for me to understand her, she talked so brokenly. All the humane characteristics I ever possessed came to the front, and I guess I shed tears. The sight of that poor helpless girl so angered me that I then promised myself that as long as there was a war-path Indian, I would camp on his trail. When she saw me approaching her she sat down in the grass.

I said: "Poor child; what can I do for you? Where are your people?" She understood me, and said she wanted something to cover her body. I dismounted, unsaddled my horse, and tossed her my top saddle-blanket. I turned my back, and she arose, wrapped the blanket around her body, and walked toward me and said: "A string." Turning toward her, I cut about four feet from the end of my lariat. Unwinding the strands, I tied one around her waist; then, folding the top of the blanket over her head and shoulders, I cut holes in under where it should fit around her neck. I ran one of the strands through and tied it so as to keep the blanket from falling down over her shoulders. I then got her on behind me and started for the troops. When I got up on the divide I was nearly two miles behind the command. It had halted upon noticing my approach from the rear. I rode up, and turned the girl over to Major Mock. The major got George Shoemaker to take her back, in hopes of finding her people, or some women to care for her.

That night we went on to the Republican river, about six miles below the forks. The Indians camped about three miles above, on a little stream sometimes called Deer creek. That night Major Mock wanted to know of me if I could find a cowboy who would carry a dispatch to Ogalalla, Nebraska. I told him I would try. I started at once to hunt one, and had gone but a little way until I met Bill Street. I asked him if he could get through to Ogalalla?

He said, "Yes."

"Well, come on to camp." I introduced him to Major Mock, and said: "Here is your man."

The major handed him the dispatch, saying, "Hurry to Ogalalla."

The next morning we went up the river and struck their last night's camp. And for a natural, fortified camp, they surely had it. I believe they expected to be attacked here. They had not been gone long, for there were live coals from the willow-brush fires, which was evidence that we were not far behind them. They struck for the breaks of the North Fork of the Republican. Across the divide, and coming up on the breaks to the north, we could see the Indians, and they us, at the same time. The Indians started to run. Mock started to a creek straight ahead, on the Frenchman's Fork of the Republican, to camp for noon.

I asked, "Major, are you not going to chase those Indians now, and stop these horrible murders of the helpless settlers?"

He said: "No, Rees, the men and horses are worn out, and must have a little rest and food."

We went to the creek, camped, but did not unsaddle. Ate a cold lunch, mounted, and took the trail, which was now easily followed. Packs were dropped; worn-out ponies left on the trail; and many garments carried from settlers' homes. Among others was a wedding dress that had been worn by Annie Pangle, who had been married in my house to a man named Bayliss. I passed on at the head of the command, and saw that Dull Knife and his band were running for their lives.

The famous Amos Chapman and I were now riding together, when we saw a pack ahead of us that looked peculiar. I dismounted to look at it. _It was a live Indian._ Pulling out my six-shooter I would have killed him, but Amos said: "Don't, Sol; here comes the major on a run; let's wait until he comes up." Amos was a good sign-talker, and tried to talk to him; but he was stoical and silent.

I put my 45 to his ear and said: "Ame, it's signs or death." He seemed to realize what would come, and sign-talk he did, a-plenty. He said he was tired out, and could not keep up, and his people had left him, not having time to stop and make a travois to take him along. Having lost so much time here, the Indians got out of sight. When the wagons came up this played-out warrior was loaded onto one, and hauled for two days, when some of the soldiers, who loved their dead Colonel Lewis, sent him to the "happy hunting-grounds" by the bullet route; and Major Mock never did find out who did it.

From where we loaded this warrior the trail was still easily followed.

About dusk the Major rode ahead again, and asked me, "How far is it to Ogalalla?"

I told him, "Six or seven miles northwest."

"Pull for there; for I have just got to have supplies."

We headed that way, and traveled to the South Platte, arriving there in the fore part of the night.

Here we remained until about 2 P. M. next day, waiting for supplies to come from Sidney. Mock thought that the Indians would pass near Ogalalla. But a telegram reached him from Fort Leavenworth, stating that Major Thornburg would soon be on the ground, with fresh troops and horses, and for him to follow Thornburg's trail. Information having been received by Thornburg that the Indians had crossed the Union Pacific Railroad, six miles east of Ogalalla, instead of west of there, as Mock had supposed they would, having killed a cowboy near where they crossed. We then followed the military road to the crossing of the North Platte. Here we found Thornburg's supply train quicksanded. Here our quartermaster, Lieutenant Wood [whom the author well knew], broke "red tape." Taking all the supplies we needed and the best of Thornburg's mules, we moved on north, and never did see him or his command of fresh troops.

In moving north we came to a small creek and found Thornburg's trail; also Dull Knife's trail. We followed them to the head of the creek. From there Thornburg turned west.

But we scouts were satisfied that an Indian ruse had been played. Riding on ahead, north, I struck a trail where some were afoot. This was evidently the squaw and pappoose trail. About twenty miles farther the trail gave out. By twos and fours they scattered like quails, having agreed on some meeting-place farther on toward their northern home; the warriors doing the same with Thornburg, when he, too, found himself without a trail. He started a dispatch across to Mock; the bearer was wounded and lost his horse. But we got the dispatch. The Indians got his horse, leaving his saddle. The dispatch was lying about twenty feet from the saddle. It seemed to me the soldier thought the dispatch might be found by some of Mock's scouts. The message called upon Mock to send him some practical scouts, as he had lost the warrior trail.

Mock could not get one of us to go. We all three thought we were pretty fair trailers and knew what Dull Knife was up to. He wanted to make us lose all the time possible, so that he and his band could concentrate many miles away toward the North Star, while we were picking up the broken threads of his trail. And he did it. Amos and Hi. reasoned the case with Mock, and I assented to all the two scouts said. So no trailers went to Thornburg.

Dull Knife and his band were finally surrounded near Fort Robinson, Nebraska; cut their way out; escaped to near Fort Keogh, Montana, where they were recaptured, and finally settled down to farming. Dull Knife died in 1885, at the age of 78 years.

While Mock, Hi., Amos and I were talking about the ruse Dull Knife had played Thornburg, a courier arrived from Fort Sidney, with a dispatch, ordering Mock's command to Sidney on the U. P. R. R. near South Platte. We lay over there a few days, and started back to the Indian Territory, with another band of disarmed northern Cheyennes, whose chief's name I do not now recall. But Dull Knife will forever ring in my ears.

There were about 300 of these Indians, men, women and children. We took a course for Wallace, Kansas. We crossed a trackless, unsettled region at the time; no roads or trails, except, at times, the evidences of the old buffalo trails, until we struck the head of Chief creek, a branch of the Republican. During the night's camp there came a heavy snow-storm; no timber, no brush or wind-breaks, and nothing but buffalo-chips to cook with. The next morning the major asked me if I could take him to timber by noon. I told him I could, but doubted if his command and wards could make it.

He asked me about the route. "For three miles to the Republican, it was good; but from there to Dead Willow over the sand-hills it was the devil's own route."

Arriving at Dead Willow we stayed three or four days, I forget which. During this time Lieutenant Wood had a bridge built, and a route laid out for crossing the Arickaree. Then we went a southeast course to the South Republican, one day's march.

Next morning Major Mock asked me if I could get a dispatch to Fort Wallace that day? I told him I could if I had a good mount. He said, "Take your pick from the command." I took Harry Coon's mule. The reason for that was I had noticed him on the entire trip. He was a careful stepper; never stumbled. Harry never used spurs or quirt on him. So I started with the message, leading my own saddle-horse. This message was urgent, and was addressed to the commanding officer at Fort Leavenworth. I got to Wallace just at sundown, and handed the message to the commanding officer at the fort.

He asked, "Where did you leave the command?"

I said, "On the Republican."

He seemed amazed. "Orderly, take this man's stock to the corral, and see they are well cared for." He invited me to his quarters. The next morning, the poor faithful mule could not walk out of the corral. I pitied him; but I had to deliver that message.

I stayed at Wallace during the four days it took the command to arrive. Here I was discharged, at my own request, as I wanted to go home. The officers all said, "Why not go on to the Indian Territory, as it amounts to $5 a day going and coming."

I said: "No; I told you before, it was not the five dollars a day I was after. It was the protection of settlers, and the love of adventure. This thing of herding Indians with no guns in their hands makes me feel cheap. But Amos and Hi. live down there, and that is all right."

After returning to my home on the Prairie Dog, I remained there, putting on improvements, until the fall of 1880. Now here on this creek, where you just had your swim, is forty-five miles to the Smoky, south, where our old friend Smoky Hill Thompson used to live; and ninety miles north is the Platte, where our leader in the Casa Amarilla battle, Hank Campbell, lived.

I liked this location and decided to keep it as my future home. But, like yourself, I am of a restless disposition. So I rented out my farm and went to New Mexico, and was gone three years. I was in business in Raton.

One day Jim Carson, a son of Kit, came into my place and said: "Mr. Rees, my mother is coming down from Taos to visit some of her Mexican friends. She has heard of you, and would be glad to see you."

You know Raton is the old Willow Springs you used to know before the Santa Fe was built down through Dick Hooten's pass, in the Raton Mountains. Well, just across the arroyo is a little Mexican hamlet, say 300 yards from Raton proper. At the time I speak of, I met the Spanish widow of the famous Kit Carson, the grand old scout, guide, and interpreter. [He was the man who piloted John C. Frémont to the Pacific Coast.] She was one of the best-preserved old ladies I ever saw, sixty-three years of age; she could talk both English and Spanish fluently, and was a perfect sign-talker. After nearly an hour's talk, she said she would like to stay there if she only had money enough to buy her a washtub, board, and some soap. (Poor soul! profligate Jim had squandered her last dollar!) I looked at her, and in silence I asked myself, "What has Kit Carson done for humanity?" I went across the arroyo and bought two washtubs, and boards, a box of soap, and several other articles. I think the bill amounted to twenty-odd dollars. I hired some Mexicans to take them to her. I had a log house with two rooms built for her. When told it was hers, she said: "Oh, I can never earn money enough to pay for this." I said: "Mrs. Carson, Kit has paid for this, through me, for what he has done to open up the West to settlers."

She moved in. In less than two months she had twelve washtubs busy; elderly Mexican women at work; all quiet and orderly; twenty-five cents apiece for washing a common woolen shirt; and every day all were as busy as could be. In three months she sent for me, and insisted that I should tell her how much money I had paid out for her. "I want to pay it and then tell you how grateful I feel toward you." I saw her meaning, for she _was a lady_. I put the price at a sum far under what I knew it had cost me. She opened a chest and handed me the money, saying: "Mr. Rees, only for you, I do not know what I should have done. I shall always feel so grateful."

Did she? Was she?

I was taken down with mountain fever. The second day I became delirious, and finally unconscious.

What did Mother Carson do? She sent four strong Mexicans to my room; came herself with them. A soft mattress was placed on a door for a litter, and I was carried to her house, placed on her own bed, and for five days and nights that angel of mercy, this simple, dignified widow of Kit's, nursed me back to life. And when consciousness was restored, she was lying across the foot of the bed, not having taken off her moccasins during that long vigil.

There is a beauty-spot picked out in the "Kingdom Come" for such noble, high-minded women.

And now, John, I guess I have told you about all there is to say. You see me now far different from what you knew me in the old days. Three years ago I had a stroke of paralysis. That accounts for my indistinct articulation, and you are one of the very few that I would talk to about the past. For, you know, you and I have gone through places that it seems incredible to this day and generation.

Yet _you_ know the Story of the Plains, especially the old Southwest as we knew it for years.

* * * * *

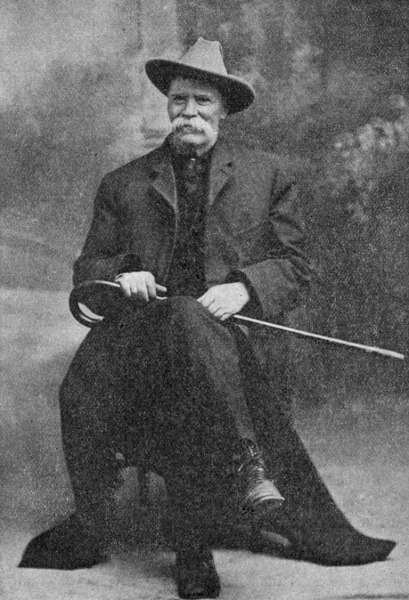

Reader, there is something more to be said. I found this man Rees at the town of Jennings, five miles down the Prairie Dog from his ranch. He is now a broken-down man in body, but has ample means. He is to-day less than sixty years of age; but he has been a man of iron. He has dared and done what the average man of to-day would shrink from. But here in the quiet of his home, where he is surrounded with the luxuries of life, he pines for buffalo-meat. He may not have a tablet of fame; yet he has a lovable wife, two interesting daughters, and three boys: John Rees, twenty-one years old, a manly man; his son Ray, a polite little fellow of twelve; and his prattling baby-boy, Wayne Solomon Rees, three years, who will some day emulate his father, and he is to-day the youngest child of an ex-soldier of the grand old Union army. His honest, open countenance, as shown in his picture in this chapter, could not help but excite the admiration of mankind.

The author congratulates himself that he has lived to see the day that he could trot this little tot on his knees, in the quiet of the Rees home, and while dancing him would think of the days that his father did deeds that were noble and courageous.

Reader, go into the quiet of this home, as I have done. Hear the girls play up-to-date music on a fine piano, that an indulgent father has purchased them. Look into John Rees's room and see the trophy of a Comanche warrior's beaded buckskin jacket that his father brought home from Texas ten years before John was born. Look at the painting on the wall of that ever-to-be-mysterious massacre.

The first night that I slept with John Rees and awoke in the morning at chicken-crow, I lay there thinking, while John was peacefully sleeping. My memory carried me back to days when his father, with a fortitude and courage born of heroes, saved the lives of eighteen men from a horrible death. Yet Mr. Seton says we were the dregs of the border towns.

I wish to speak of Georgia Rees: Her father loves the jingle of "Marching Through Georgia," the old war-song from "Atlanta to the Sea;" and as Georgia plays this inspiring song at her father's request, Sol. keeps time to the music, by thumping his cane on the floor. And that is why the author thinks he named the baby-girl Georgia.