On that memorable night, June 26, 1874, there were 28 men and one woman at the Walls. The woman was the wife of William Olds. She had come from Dodge City with her husband to open a restaurant in the rear of Rath & Wright's store. Only eight or nine of the men lived at the Walls, the others being buffalo-hunters who by chance happened to be there. There was not the slightest feeling of impending danger.

As was the custom in the buffalo country, most of the men made their beds outside on the ground. I spread my blankets near the blacksmith's shop, close to my wagon. I placed my gun by my side between my blankets, as usual, to protect it from dew and rain. A man's gun and his horse were his two most valuable possessions, next to life, in that country in those days.

Every door was left wide open, such a thing as locking a door being unheard of at the Walls. One by one the lights were turned out, the tired buffalo-hunters fell asleep, and the Walls were soon wrapped in the stillness of night.

Late that evening I had gone down on the creek and caught my saddle horse--a better one could not be found--and tied him with a long picket rope to a stake pin near my wagon.

About 2 o'clock in the morning Shepherd and Mike Welch, who were sleeping in Hanrahan's saloon, were awakened by a report that sounded like the crack of a rifle. They sprang up and discovered that the noise was caused by the big cottonwood ridge pole.

This ridge pole sustained the weight of the dirt roof, and if the pole should break the roof would collapse and fall in, to the injury or death of those inside. Welch and Shepherd woke up a number of their companions to help them repair the roof. Some climbed on top and began throwing off the dirt, while others went down to the creek to cut a prop for the ridge pole.

This commotion woke up others, and in a little while, about fifteen men were helping repair the roof. Providential things usually are mysterious; there has always been something mysterious to me in the loud report that came from that ridge pole in Hanrahan's saloon. It seems strange that it should have happened at the very time it did, instead of at noon or some other hour, and, above all, that it should have been loud enough to wake men who were fast asleep. Twenty-eight men and one woman would have been slaughtered if the ridge pole in Hanrahan's saloon had not cracked like a rifle shot.

By the time we had put the prop in place, the sky was growing red in the east, and Hanrahan asked me if I did not think we might as well stay up and get an early start. I agreed, and he sent Billy Ogg down on the creek to get the horses. Some of the men, however, crawled back into bed. The horses were grazing southeast of the buildings, along Adobe Walls Creek, a quarter of a mile off.

Turning to my bed, I rolled it up and threw it on the front of my wagon. As I turned to pick up my gun, which lay on the ground, I looked in the direction of our horses. They were insight. Something else caught my eye. Just beyond the horses, at the edge of some timber, was a large body of objects advancing vaguely in the dusky dawn toward our stock and in the direction of Adobe Walls. Though keen of vision, I could not make out what the objects were, even by straining my eyes.

Then I was thunderstruck. The black body of moving object suddenly spread out like a fan, and from it went up one single, solid yell--a war-whoop that seemed to shake the very air of the early morning. Then came the thudding roar of running horses, and the hideous cries of the individual warriors, each embarked in the onslaught. I could see that hundreds of Indians were coming. Had it not been for the ridge pole, all of us would have been asleep.

In such desperate emergencies, men exert themselves almost automatically to do the needful thing. There is no time to make conscious effort, and if a man lose his head, he shakes hands with death.

I made a dash for my saddle horse, my first thought being to save him. I never thought for an instant that the oncoming Indians were intending an attack upon the buildings, their purpose being, as I thought, to run off our stock, which they could easily have done by driving it ahead of them. I overlooked the number of Indians, however, or else I might have formed a different opinion.

The first mighty war-whoop had frightened my horse until he was frantic. He was running and lunging on his rope so violently that in one more run he would have pulled up the stake pin and gone to the land of stampeded horses. I managed to grab the rope, and tie my horse to my wagon.

I then rushed for my gun and turned to get a few good shots before the Indians could turn to run away. I started to run forward a few steps. Indians running away! They were coming as straight as a bullet toward the buildings, whipping their horses at every jump.

There was never a more splendidly barbaric sight. In after years, I was glad that I had seen it. Hundreds of warriors, the flower of the fighting men of the southwestern Plains tribes, mounted upon their finest horses, armed with guns and lances, and carrying heavy shields of thick buffalo hide, were coming like the wind. Over all was splashed the rich colors of red, vermillion and ochre, on the bodies of the men, on the bodies of the running horses. Scalps dangled from bridles, gorgeous war-bonnets fluttered their plumes, bright feathers dangled from the tails and manes of the horses, and the bronzed, half-naked bodies of the riders glittered with ornaments of silver and brass. Behind this head-long charging host stretched the Plains, on whose horizon the rising sun was lifting its morning fires. The warriors seemed to emerge from this glowing background.

I must confess, however, that the landscape possessed little interest for me when I saw that the Indians were coming to attack us and that they would be at hand in a few moments. War-whooping had a very appreciable effect upon the roots of a man's hair.

I fired one shot but had no desire to wait and see where the bullet went. I turned and ran as quickly as possible to the nearest building, which happened to be Hanrahan's saloon. I found it closed. I certainly felt lonesome. The alarm had spread and the boys were preparing to defend themselves. I shouted to them to let me in. An age seemed to pass before they opened the door and I sprang inside. Bullets were whistling and knocking up the dust all around me. Just as the door was opened for me, Billy Ogg ran up and fell inside, so exhausted that he could no longer stand. I am confident that if Billy had been timed, his would have been forever the world's record. Billy had made a desperate race, and that he should escape seemed incredible.

We were scarcely inside before the Indians had surrounded all the buildings and shot out every window pane. When our men saw the Indians coming, they broke for the nearest building at hand, and in this way split up into three parties. They were gathered in the different buildings, as follows:

Hanrahan's Saloon--James Hanrahan, "Bat" Masterson, Mike Welch, Shepherd, Hiram Watson, Billy Ogg, James McKinley, "Bermuda" Carlisle, and William Dixon.

Myers & Leonard's Store--Fred Leonard, James Campbell, Edward Trevor, Frank Brown, Harry Armitage, "Dutch Henry," Billy Tyler, Old Man Keeler, Mike McCabe, Henry Lease, and "Frenchy."

Rath & Wright's Store--James Longton, George Eddy, Thomas O'Keefe, William Olds and his wife; Sam Smith, and Andy Johnson.

Some of the men were still undressed, but nobody wasted any time hunting their clothes, and many of them fought for their lives all that summer day barefoot and in their night clothes.

The men in Hanrahan's saloon had a little the best of the others because of the fact that they were awake and up when the alarm was given. In the other buildings, some of the boys were sound asleep and it took time for them to barricade the doors and windows before they began fighting. Barricades were built by piling up sacks of flour and grain, at which some of the men worked while others seized their guns and began shooting at the Indians.

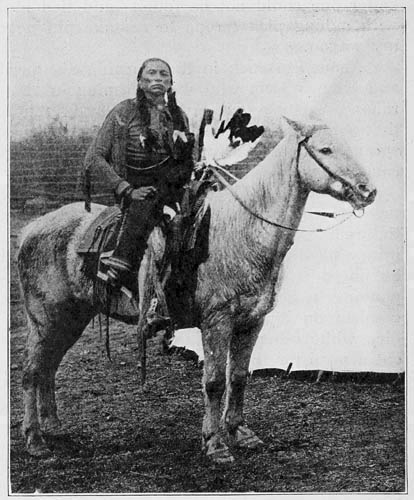

The number of Indians in this attack has been variously estimated at from 700 to 1,000. I believe that 700 would be a safe guess. The warriors were mostly Kiowas, Cheyennes and Comanches. The latter were led by their chief Quanah, whose mother was a white woman, Cynthia Ann Parker, captured during a raid by the Comanches in Texas. Big Bow was another formidable Comanche chieftain; Lone Wolf was a leader of the Kiowas, and Little Robe and White Shield, of the Cheyennes.

For the first half hour the Indians were reckless and daring enough to ride up and strike the doors with the butts of their guns. Finally, the buffalo-hunters all got straightened out and were firing with deadly effect. The Indians stood up against this for awhile, but gradually began falling back, as we were emptying buckskin saddles entirely too fast for Indian safety. Our guns had longer range than theirs. Furthermore, the hostiles were having little success--they had killed only two of our men, the Shadler brothers who were caught asleep in their wagon. Both were scalped. Their big Newfoundland dog, which always slept at their feet, evidently showed fight, as the Indians killed him, and "scalped" him by cutting a piece of hide off his side. The Indians ransacked the wagon and took all the provisions. The Shadlers were freighters.

At our first volleys, a good many of the Indians jumped off their horses and prepared for a fight on foot. They soon abandoned this plan; and for good reason. They were the targets of expert rough-and-ready marksmen, and for the Indians to stand in the open meant death. They fell back.

The Indians exhibited one of their characteristic traits. Numbers of them fell, dead or wounded, close to the buildings. In almost every instance a determined effort was made to rescue the bodies, at the imminent risk of the life of every warrior that attempted this feat in front of the booming buffalo-guns. An Indian in those days would quickly endanger his own life to carry a dead or helpless comrade beyond reach of the enemy. I have been told that their zeal was due to some religious belief concerning the scalp-lock--that if a warrior should lose his scalp-lock his spirit would fail to reach the happy hunting grounds. Perhaps for the same reason the Indian always tried to scalp his fallen enemy.

Time and again, with the fury of a whirlwind, the Indians charged upon the building, only to sustain greater losses than they were able to inflict. This was a losing game, and if the Indians kept it up we stood a fair chance of killing most of them. I am sure that we surprised the Indians as badly as they surprised us. They expected to find us asleep, unprepared for an attack. Their "medicine" man had told them that all they would have to do would be to come to Adobe Walls and knock us on the head with sticks, and that our bullets would not be strong enough to break an Indian's skin. The old man was a bad prophet.

Almost at the beginning of the attack, we were surprised at the sound of a bugle. This bugler was with the Indians, and could blow the different calls as cleverly as the bugler on the parade ground at Fort Dodge. The story was told that he was a negro deserter from the Tenth Cavalry, which I never believed. It is more probable that he was a captive halfbreed Mexican that was known to be living among the Kiowas and Comanches in the '60s. He had been captured in his boyhood when these Indians were raiding in the Rio Grande country, and grew up among them, as savage and cruel as any of their warriors. How he learned to blow the bugle is unknown. A frontiersman who went with an expedition to the Kiowas in 1866 tells of having found a bugler among them at that time. The Kiowas, he said, were able to maneuver to the sound of the bugle. This bugler never approached the white men closely enough to be recognized.

In the fight at Adobe Walls, the fact was discovered that the Indian warriors were charging to the sound of the bugle. In this they "tipped" their hand, for the calls were understood, and the buffalo-hunters were "loaded for bear" by the time the Indians were within range. "Bat" Masterson, recalling this incident long after the fight, said:

"We had in the building I was in (Hanrahan's saloon), two men who had served in the United States army, and understood all the bugle calls. The first call blown was a rally, which our men instantly understood. The next was a charge, and that also was understood, and immediately the Indians come rushing forward to a fresh attack. Every bugle call he blew was understood by the ex-soldiers and were carried out to the letter by the Indians, showing that the bugler had the Indians thoroughly drilled.

"The bugler was killed late in the afternoon of the first day's fighting as he was running away from a wagon owned by the Shadler brothers, both of whom were killed in this same wagon. The bugler had his bugle with him at the time he was shot by Harry Armitage. Also he was carrying a tin can filled with sugar and another filled with ground coffee, one under each arm. Armitage shot him through the back with a 50-caliber Sharp's rifle, as he was making his escape."

Billy Tyler and Fred Leonard went into the stockade, but were compelled to retreat, the Indians firing at them through the openings between the stockade pickets. Just as Tyler was entering the door of the adobe store, he turned to fire, and was struck by a bullet that penetrated his lungs. He lived about half an hour after he was dragged into the store.

The Indians were not without military tactics in trying to recover their dead and wounded. While one band would pour a hot fire into the buildings, other Indians on horseback would run forward under the protection of this fusillade. They succeeded in dragging away a good many of the fallen.

Once during a charge I noticed an Indian riding a white horse toward where another Indian had gone down in the tall grass. The latter jumped up behind the Indian on the horse, and both started at full speed for safety. A rifle cracked and a bullet struck the horse, breaking one of its hind legs. We could see the blood streaming down the horse's leg. Both Indians began whipping the poor brute and, lurching and staggering on three legs, he carried them away.

By noon the Indians had ceased charging, and had stationed themselves in groups in different places, maintaining a more or less steady fire all day on the buildings. Sometimes the Indians would fire especially heavy volleys, whereupon wounded Indians would leap from the grass and run as far as they could and then drop down in the grass again. In this manner a number escaped.

Along about 10 o'clock, the Indians having fallen back at a safer distance from the buffalo-guns, some of us noticed a pony standing near the corner of a big stack of buffalo hides at the rear of Rath's building. We could see that an Indian behind the hides was holding the pony by the bridle, so we shot the pony and it fell dead. The pony was gaily decorated with red calico plaited in its mane.

The falling of the pony left the Indian somewhat exposed to our fire, and the boys at Hanrahan's and Rath's opened upon him full blast. They certainly "fogged" him. No Indian ever danced a livelier jig. We kept him jumping like a flea back and forth behind the pile of hides.

I had got possession of a big "50" gun early in the fight, and was making considerable noise with it. I sized up what was going on behind the pile of buffalo hides, and took careful aim at the place where I thought the Indian was crouched. I shot through one corner of the hides. It looked to me as if that Indian jumped six feet straight up into the air, howling with pain. Evidently I had hit him. He ran zig-zag fashion for thirty or forty yards, howling at every jump, and dropped down in the tall grass. Indians commonly ran in this manner when under fire, to prevent our getting a bead on them.

I managed to get hold of the "50" gun in this manner. The ammunition for mine was in Rath's store, which none of us was in the habit of visiting at that particular moment. I had noticed that Shepherd, Hanrahan's bartender, was banging around with Hanrahan's big "50," but not making much use of it, as he was badly excited.

"Here, Jim," I said to Hanrahan, "I see you are without a gun; take this one."

I gave him mine. I then told "Shep." to give me the "50." He was so glad to turn loose of it, and handed it to me so quickly that he almost dropped it. I had the reputation of being a good shot and it was rather to the interest of all of us that I should have a powerful gun.

We had no way of telling what was happening to the men in the other buildings, and they were equally ignorant of what was happening to us. Not a man in our building had been hit: I could never see how we escaped, for at times the bullets poured in like hail and made us hug the sod walls like gophers when a hawk was swooping past.

By this time there were a large number of wounded horses standing near the buildings. A horse gives up quickly when in pain, and these made no effort to get away. Even those that were at a considerable distance from the buildings when they received their wounds came to us, as if seeking our help and sympathy. It was a pitiable sight, and touched our hearts, for the boys loved their horses. I noticed that horses that had been wounded while grazing in the valley also came to the buildings, where they stood helpless and bleeding or dropped down and died.

We had been pouring a pile of bullets from our stronghold, and about noon were running short of ammunition. Hanrahan and I decided that it was time to replenish our supply, and that we would have to make a run for Rath's store, where there were thousands of rounds which had been brought from Dodge City for the buffalo-hunters.

We peered cautiously outside to see if any Indians were ambushed where they could get a pot shot at us. The coast looked clear, so we crawled out of a window and hit the ground running, running like jack-rabbits, and made it to Rath's in the fastest kind of time. The Indians saw us, however, before the boys could open the door, and opened at long range. The door framed a good target. I have no idea how many guns were cracking away at us, but I do know that bullets rattled round us like hail. Providence seemed to be looking after the boys at Adobe Walls that day, and we got inside without a scratch, though badly winded.

We found everybody at Rath's in good shape. We remained here some time. Naturally, Hanrahan wanted to return to his own building, and he proposed that we try to make our way back. There were fewer men at Rath's than at any other place, and their anxiety was increased by the presence of a woman, Mrs. Olds. If the latter fact should be learned by the Indians there was no telling what they might attempt, and a determined attack by the Indians would have meant death for everybody in the store, for none would have suffered themselves to be taken alive nor permitted Mrs. Olds to be captured.

The boys begged me to stay with them. Hanrahan finally said that he was going back to his own place, telling me that I could do as I thought best. Putting most of his ammunition into a sack, we opened the door quickly for him, and away he went, doing his level best all the way to his saloon, which he reached without mishap.