The early history of the Santa Fe Trail, which runs parallel with the Santa Fe Railroad for hundreds of miles, is somewhat obscured by mystery and tradition, but from historical data in possession of the Museum of New Mexico, at Santa Fe, it can be stated with a large degree of accuracy that the trail was started by Spanish explorers three hundred years ago.

The first known expedition by Americans over the trail was made by the Mallet brothers, who arrived in Santa Fe, July 22, 1739. The first trader to follow the trail reached Santa Fe in 1763. It was not until 1804 that LaLande, a trapper and hunter, crossed the trail and made Santa Fe that year. Kit Carson was one of those who struck the trail in 1826, when he was but sixteen years of age.

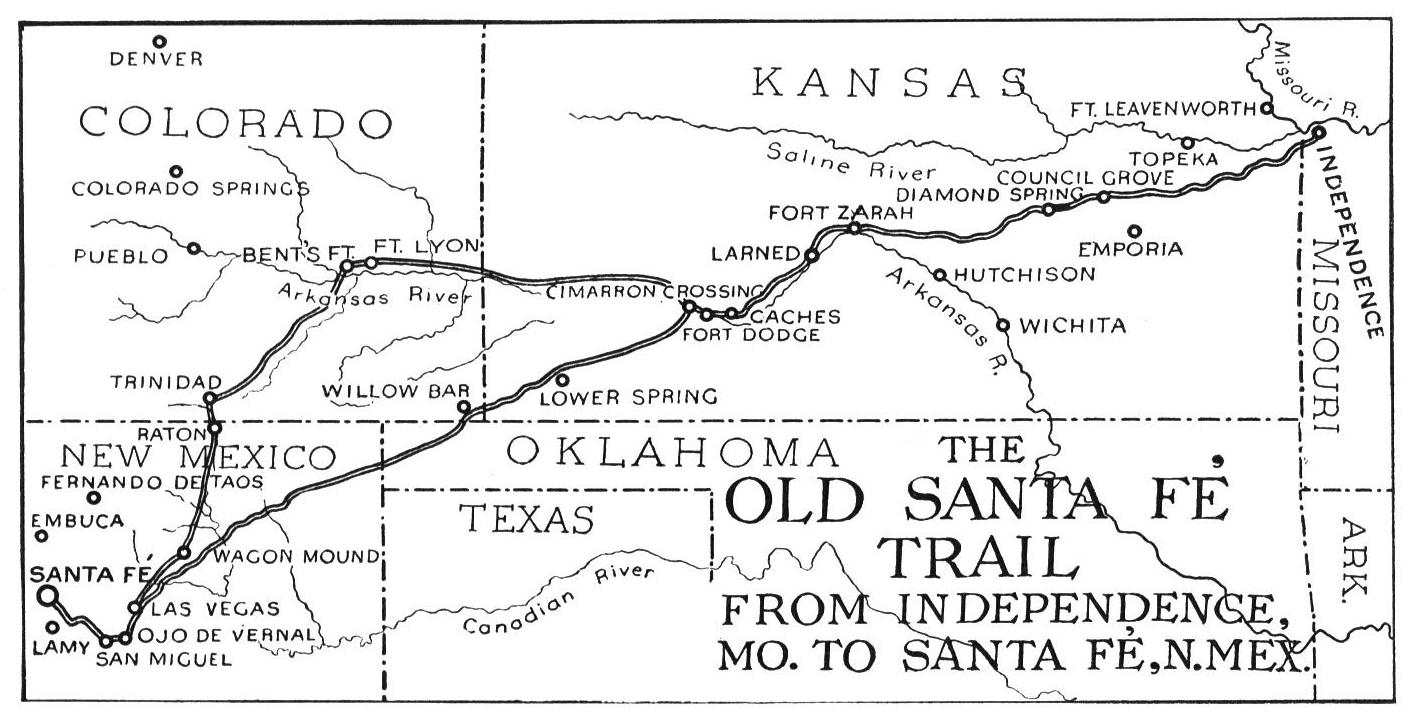

The camping stations along the trail at that time were Diamond Spring, Lost Spring, Cottonwood Creek, Turkey Creek, Cow Creek (now Hutchinson, Kansas), and further on was Pawnee Rock, a famous landmark of sandstone, twenty feet high.

From the year 1820 many caravans made their way over the trail to Santa Fe, then, as it is to-day, the seat of government. It was here in the old palace that some of the early governors had lived in a semi-royal state, maintaining a little court and body-guards whose lives were by no means a sinecure, since they were called upon to fight the Indians on many occasions.

These Indians developed great hostility to the white man, and caravans on the trail were so frequently attacked, and so many tragedies stained the trail with the blood of women and children, that in 1823, Colonel Viscarra, Jefè Politicio, of New Mexico, commanded a battalion of Mexican troops in protecting the caravans on the Santa Fe trail. His hand-full of men, and the predatory and blood-thirsty character of the Indians, made it impossible for him to protect any large part of the trail, and soldiers, traders and their families were massacred by overwhelming numbers, the victims including many women and children. The members of one caravan met their fate in sight of Santa Fe, forty-six days out from St. Louis.

Colonel Viscarra had not only to deal with one tribe, but many. There were the Navajos, Pawnees, Arapahos, Kiowas, Comanche, Apache and Cheyenee. There was only one tribe friendly to the traders, and that was the Pueblo Indians.

In August, 1829, a particularly vicious attack on a caravan on the Santa Fe trail, bound for Santa Fe, caused the traders to petition the government for military protection, and as a result this year, under agreement with the Government of the United States and the Republic of Mexico, four companies of United States troops guarded the great caravans moving from Western Missouri to Santa Fe, as far as the Arkansas River. In spite of this protection, however, attacks by Indians were a common occurrence, and every caravan had to carry arms and ammunition, and vigilance was never relaxed from the time they left the Arkansas River until they struck the plaza at Santa Fe.

Colonel Viscarra, a handsome, picturesque Spaniard, always mounted on a mettlesome thoroughbred, was probably the most dashing figure in the history of the Santa Fe trail. Tales of his gallantry and daring became folklore among the traders, pioneers and their descendants.

In 1843, the American traders commenced to establish regular communication between Missouri and Santa Fe and in 1849, started to run a stage from Independence, Mo., to Santa Fe. The fare was $250. Each passenger was allowed forty pounds of baggage. The capacity of the coach was ten passengers in addition to the driver and messenger. Relays of horses were stationed along the trail every fifteen to twenty miles.

The vehicles used by the traders and pioneers were for the greater part Conestoga wagons drawn by horses or mules. As they proceeded westward it was a common sight to see on the trail, “creoles, polished gentlemen magnificently clothed in Spanish costume, exiled Spaniards escaping from Mexico, and richly caparisoned horses, mules and asses, and a courtesy of the road grew out of a common dangerâ€.

The most terrible part of the trail was the great plain between the Arkansas River and Cimarron Spring. It was over three thousand feet above sea level and sixty-three miles without a water course or pool. The soil was dry and hard and short buffalo grass and some cacti were the only evidence of the parched vegetation. There was not a shrub or tree of any kind. It was a sandy desert plain and it was here the traveler saw the mirage, a beautiful lake which disappeared as he approached it.

Breakdowns on this plain were frequent, and the Indians most dangerous. Dry, hot weather prevailed with the blue sky overhead, and over these parched wastes of the desert, exposed to attacks by Indians both night and day, the caravans finally reached Cimarron Spring, which was in a small ravine.

After leaving Cimarron Spring (445 miles from Independence, Missouri), the caravans struck the following camps:

Willow Bar; Cold Spring; Rabbit Ear Creek; Round Mound; Rock Creek; Point of Rocks; Rio Colorado; Ocaté Creek; Santa Clara Spring (Wagon Mound); Rio Mora; Rio Gallinas (Las Vegas); Ojo De Bernal Spring; San Miguel; Pecos Village;

and finally Santa Fe, a distance of 750 miles from Independence, Missouri, the starting point.

The old Santa Fe Trail led from Franklin, Missouri, through Kansas, Colorado, Oklahoma and New Mexico. It followed the Arkansas River to Cimarron Crossing (Fort Dodge) to La Junta, Colorado; then south, crossing the Raton Pass, joining the main trail at Santa Clara Spring.

The passenger looking out of the window of the train on the Santa Fe Railroad will see this trail running for miles parallel with the track, and will be able to people it with the historic traditions which have made the Santa Fe Trail one of the most romantic and, withal, one of the most tragic national highways in the United States.

NOTE.--The greater part of the information given in this brief history is taken from _Twitchell on Leading Facts of New Mexico History_.