Whenever the history of the Southwest shall be written, more than one long and interesting chapter must be devoted to the first permanent settlement on its plains and the first permanent settler there. In the accounts of that wide territory through which the old Santa Fé trail passed, William Bent and Bent’s Old Fort have frequent mention.

Who were the Bents and whence did they come?

Silas Bent was born in the Colony of Massachusetts in 1768. His father is said to have been one of those who attended the famous “Boston Tea Party.” Silas was educated for the bar and came to St. Louis in 1804 at the time the government of Louisiana was turned over to the American authorities. Here he served as a judge of the Superior Court, and here he resided until his death, in 1827.

Of his seven sons, John was educated for the bar and became a well-known attorney of St. Louis. The youngest son, Silas, as flag lieutenant of the flag-ship “Mississippi,” was with Perry in Japan, and wrote a report on the Japan current for an American scientific society. He delivered addresses on meteorology in St. Louis in 1879, and on climate as affecting cattle breeding in the year 1884. Four other sons--Charles, William W., and later George and Robert--were prominent in the Indian trade on the upper Arkansas and elsewhere between 1820 and 1850, and remained trading in that region until they died.

The leading spirit in this family of Indian traders was William W. Bent. Early in life Charles and William Bent had been up on the Missouri River working for the American Fur Company. Colonel Bent stated to his son George that he went up there in the year 1816, when very young.[5] Very likely he was then a small boy only ten or twelve years old. It was there that Charles and William Bent became acquainted with Robert Campbell, of St. Louis, who remained a firm friend of the brothers throughout his life. William Bent could speak the Sioux language fluently and the Sioux had called him Wa-si´cha-chischi´-la, meaning Little White Man, a name which confirms the statement that he entered the trade very young, and seems to warrant the belief that his work for the fur company was at some post in the Sioux country.

[5] The history of _The Bent Family in America_ gives the date of William Bent’s birth as 1809, which can hardly be made to agree with this statement.

In his testimony before the joint commission which inquired into Indian affairs on the plains in 1865, William Bent stated that he had first come to the upper Arkansas and settled near the Purgatoire, just below the present city of Pueblo, Colorado, in 1824; that is to say, two years before he and his brother began to erect their first trading establishment on the Arkansas. Previous to this time William Bent had been trapping in the mountains near there, and may very well have done some individual trading with the Indians.

William Bent was undoubtedly the first permanent white settler in what is now Colorado, and for a very long time he was not only its first settler, but remained its most important white citizen.

By his fair and open dealings, by his fearless conduct, and by his love of justice, William Bent soon won the respect and confidence of the Indians with whom he had to do. Among the rough fraternity of mountain trappers he was also very popular, his reputation for courage being remarkable even among that class of daring men. He was tirelessly active in prosecuting the aims of his trade, making frequent trips to the camps of the various tribes with which he, and later his company, had dealings, and to the Mexican settlements in the valley of Taos and to Santa Fé. Every year, probably from 1824 to 1864, he made at least one journey from the fort on the Arkansas, across the plains of Colorado, Kansas, and Missouri, to the settlements on the Missouri frontier.

About 1835 William Bent married Owl Woman, the daughter of White Thunder, an important man among the Cheyennes, then the keeper of the medicine arrows. Bent’s Fort was his home, and there his children were born, the oldest, Mary, about 1836, Robert in 1839--his own statement made in 1865 says 1841--George in July, 1843, and Julia in 1847. Owl Woman died at the fort in 1847 in giving birth to Julia, and her husband afterward married her sister, Yellow Woman. Charles Bent was the child of his second marriage.

William Bent appears to have been the first of the brothers to go into the Southwestern country to trade for fur, but Charles is said to have gone to Santa Fé as early as 1819, and a little later must have joined William. The two, with Ceran St. Vrain and one of the Chouteaus, established the early trading post near the Arkansas. After occupying this stockade for two years or more, they moved down below Pueblo and built another stockade on the Arkansas. Two years later they began to build the more ambitious post afterward known as Bent’s, or Fort William, or Bent’s Old Fort. George and Robert Bent apparently did not come out to the fort until after it was completed--perhaps after it had been for some time in operation. Benito Vasquez was at one time a partner in the company.

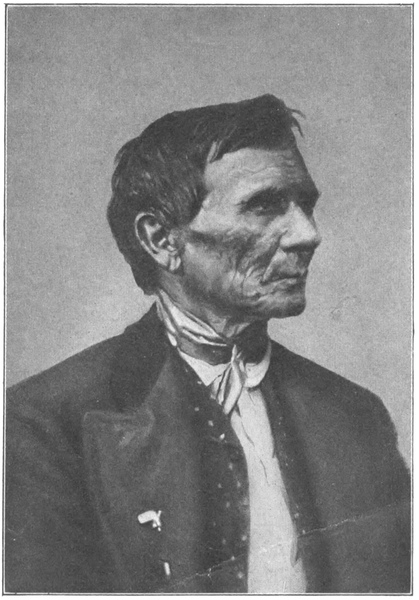

Image: BLACK BEAVER, DELAWARE SCOUT

Image: GEORGE BENT

It was in 1828 that the Bent brothers, with St. Vrain, began this large fort, fifteen miles above the mouth of Purgatoire River. It was not completed until 1832. Four years seems a long time to be spent in the construction of such a post, even though it was built of adobe brick, but there were reasons for the delay. Charles Bent was determined that the fort should be built of adobes in order to make it fireproof, so that under no circumstances could it be burned by the Indians. Besides that, adobes were much more durable and more comfortable--cool in summer, warm in winter--than logs would have been. When the question of how the fort should be built had been decided, Charles Bent went to New Mexico, and from Taos and Santa Fé sent over a number of Mexicans to make adobe brick. With them he sent some wagon-loads of Mexican wool to mix with the clay of the bricks, thus greatly lengthening the life of the adobes.

Only a short time, however, after the laborers had reached the intended site of the fort, smallpox broke out among them, and it was necessary to send away those not attacked. William Bent, St. Vrain, Kit Carson, and other white men who were there caught the smallpox from the Mexicans, and though none died they were so badly marked by it that some of the Indians who had known them well in the early years of the trading did not recognize them when they met again.

During the prevalence of the smallpox at the post William Bent sent a runner, Francisco, one of his Mexican herders, north, to warn the Cheyennes not to come near the post. Francisco set out for the Black Hills, and on his way encountered a large war-party of Cheyennes on their way to the fort. He told them of what had happened, and warned them to return north and not to come near the post until sent for. The Cheyennes obeyed, and it was not until some time later, when all at Fort William had recovered and when the temporary stockade with all the infected material that it contained had been burned, that Bent and St. Vrain, with a few pack-mules, started north for the Black Hills to find the Cheyennes and invite them to return to the post. The year of this journey has been given me as 1831. Perhaps it may have been a year earlier.

After the smallpox had ceased, more Mexican laborers were sent for, and work on the fort was resumed. Not long before his death, Kit Carson stated that at one time more than a hundred and fifty Mexicans were at work on the construction of the post.

Accounts of the dimensions of the fort differ, but on certain points all agree: that it was of adobes, set square with the points of the compass, and on the north bank of the Arkansas River. Garrard says that the post was a hundred feet square and the walls thirty feet in height. Another account says that the walls ran a hundred and fifty feet east and west and a hundred feet north and south, and that they were seventeen feet high. J. T. Hughes, however, in his _Doniphan’s Expedition_, printed in Cincinnati in 1848, says:

“Fort Bent is situated on the north bank of the Arkansas, 650 miles west of Fort Leavenworth, in latitude 38° 2´ north, and longitude 103° 3´ west from Greenwich. The exterior walls of this fort, whose figure is that of an oblong square, are fifteen feet high and four feet thick. It is 180 feet long and 135 feet wide and is divided into various compartments, the whole built of adobes or sun-dried bricks.”

At the southwest and northeast corners of these walls were bastions, or round towers, thirty feet in height and ten feet in diameter inside, with loopholes for muskets and openings for cannon. Garrard speaks of the bastions as hexagonal in form.

Around the walls in the second stories of the bastions hung sabres and great heavy lances with long, sharp blades. These were intended for use in case an attempt were made to take the fort by means of ladders put up against the wall. Besides these cutting and piercing implements, the walls were hung with flint-lock muskets and pistols.

In the east wall of the fort was a wide gateway formed by two immense swinging doors made of heavy planks. These doors were studded with heavy nails and plated with sheet-iron, so that they could never be burned by the Indians. The same was true of the gateway which entered the corral, to be described later.

Over the main gate of the fort was a square watch tower surmounted by a belfry, from the top of which rose a flagstaff. The watch tower contained a single room with windows on all sides, and in the room was an old-fashioned long telescope, or spy-glass, mounted on a pivot. Here certain members of the garrison, relieving each other at stated intervals, were constantly on the lookout. There was a chair for the watchman to sit in and a bed for his sleeping. If the watchman, through his glass, noticed anything unusual--for example, if he saw a great dust rising over the prairie--he notified the people below. If a suspicious-looking party of Indians was seen approaching, the watchman signalled to the herder to bring in the horses, for the stock was never turned loose, but was always on herd.

In the belfry, under a little roof which rose above the watch tower, hung the bell of the fort, which sounded the hours for meals. Two tame white-headed eagles kept at the fort were sometimes confined within this belfry, or at others were allowed to fly about free, returning of their own accord to sleep in the belfry. One of these eagles finally disappeared, and for a long time it was not known what had become of it. Then it was learned that it had been killed for its feathers by a young Indian at some distance from the fort.

Image: PLAN OF BENT’S OLD FORT

At the back of the fort over the gate, which opened into the corral, was a second-story room rising high above the walls, as the watch tower did in front. This room--an extraordinary luxury for the time--was used as a billiard-room during the later years of the post. It was long enough to accommodate a large billiard-table, and across one end of the room ran a counter, or bar, over which drinkables were served. These luxuries were brought out by Robert and George Bent, young men who did not come out to the fort until some time after it had been constructed, and who, being city-dwellers--for I have no record of their having any early experience of frontier life--no doubt felt that they required city amusements.

The watch tower and billiard-room were supported on heavy adobe walls running at right angles to the main enclosing walls of the fort, and these supporting walls formed the ends of the rooms on either side of the gates in the outer walls.

The stores, warehouses, and living-rooms of the post were ranged around the walls, and opened into the patio, or courtyard--the hollow square within. In some of the books dealing with these old times it is said that when the Indians entered the fort to trade, cannon were loaded and sentries patrolled the walls with loaded guns. This may have been true of the early days of the fort, but it was not true of the latter part of the decade between 1840 and 1850. At that time the Indians, or at least the Cheyenne Indians, had free run of the post and were allowed to go upstairs, on the walls, and into the watch tower. The various rooms about the courtyard received light and air from the doors and windows opening out into this courtyard, which was gravelled. The floors of the rooms were of beaten clay, as was commonly the case in Mexican houses, and the roofs were built in the same fashion that long prevailed in the West. Poles were laid from the front wall to the rear, slightly inclined toward the front. Over these poles twigs or brush were laid, and over the brush clay was spread, tramped hard, and gravel thrown over this. These roofs were used as a promenade by the men of the fort and their families in the evenings. The top of the fort walls reached about four feet above these roofs, or breast-high of a man, and these walls were pierced with loopholes through which to shoot in case of attack.

Hughes in his _Doniphan’s Expedition_ says: “The march upon Santa Fé was resumed Aug. 2, 1846, after a respite of three days in the neighborhood of Fort Bent. As we passed the fort the American flag was raised in compliment to our troops and in concert with our own streamed most animatingly on the gale that swept from the desert, while the tops of the houses were crowded with Mexican girls and Indian squaws, beholding the American Army.”

On the west side of the fort and outside the walls was the horse corral. It was as wide as the fort and deep enough to contain a large herd. The walls were about eight feet high and three feet thick at the top. The gate was on the south side of the corral, and so faced the river. It was of wood, but was completely plated with sheet-iron. More than that, to prevent any one from climbing in by night, the tops of the walls had been thickly planted with cactus--a large variety which grows about a foot high and has great fleshy leaves closely covered with many and sharp thorns. This grew so luxuriantly that in some places the leaves hung down over the walls, both within and without, and gave most efficient protection against any living thing that might wish to surmount the wall.

Through the west wall of the fort a door was cut, leading from the stockade into the corral, permitting people to go through and get horses without going outside the fort and opening the main gate of the corral. This door was wide and arched at the top. It was made large enough, so that in case of necessity--if by chance an attacking party seemed likely to capture the horses and mules in the corral--the door could be opened and the herd run inside the main stockade.

About two hundred yards to the south of the fort, and so toward the river bank, on a little mound, stood a large ice-house built of adobes or sun-dried bricks. In winter when the river was frozen this ice-house was filled, and in it during the summer was kept all the surplus fresh meat--buffalo tongues, antelope, dried meat and tongues--and also all the bacon. At times the ice-house was hung thick with flesh food.

On hot days, with the other little children, young George Bent used to go down to the ice-house and get in it to cool off, and his father’s negro cook used to come down and send them away, warning them not to go in there from the hot sun, as it was too cold and they might get sick. This negro cook, Andrew Green by name, a slave owned by Governor Charles Bent, was with him when he was killed in Taos, and afterward came to the fort and was there for many years, but was at last taken back to St. Louis and there set free. He had a brother “Dick,” often mentioned in the old books.

Besides Bent’s Fort, Bent and St. Vrain owned Fort St. Vrain, on the South Platte, opposite the mouth of St. Vrain’s Fork, and Fort Adobe, on the Canadian. Both these posts were built of adobe brick. Fort St. Vrain was built to trade with the Northern Indians; that is, with the Sioux and Northern Cheyennes, who seldom got down south as far as the Arkansas River, and so would not often come to Fort William. The Fort Adobe on the Canadian was built by request of the chiefs of the Kiowa, Comanche, and Apache to trade with these people. The chiefs who made this request were To´hau sen (Little Mountain) and Eagle-Tail Feathers, speaking for the Kiowa, Shaved Head for the Comanche, and Poor (Lean) Bear for the Apache.

These in their day were men of importance. Shaved Head was a great friend of the whites and a man of much influence with his own people and with neighboring tribes. He wore the left side of his head shaved close, while the hair on the right side was long, hanging down to his waist or below. His left ear was perforated with many holes made by a blunt awl heated red-hot, and was adorned with many little brass rings. Before peace was made between the Kiowas, Comanches, and Apaches in the year 1840, the last three tribes were more or less afraid to visit Fort William, lest they should there meet a large camp of their enemies, and Colonel Bent and the traders were also especially anxious to avoid any collision at the fort. Each tribe would expect the trader to take its part, and this he could not do without incurring the enmity of the other tribes. The wish of the trader was to be on good terms with all tribes, and this William Bent accomplished with singular discretion. Although he had a Cheyenne wife, he was on excellent terms, and always remained so, with the enemies of the Cheyennes.

Both Fort St. Vrain and Fort Adobe, being built of adobes, lasted for a long time, and their ruins have been seen until quite recently. Near the ruins of Fort Adobe two important fights have taken place, to be referred to later.

In the business of the fort William Bent had the direction of the trade with the Indians, while his brother Charles seems to have had more to do with affairs in the Mexican settlements, until his death there, at the hands of the Mexicans and Pueblos, in the year 1847. It is not certain when St. Vrain, Lee, and Benito Vasquez became partners in the business, nor how long they were interested in it. George and Robert Bent, who came out from St. Louis, certainly later than the two elder brothers, may have been partners, but there is nothing to show that they were so. Robert died in 1847.

Some time before this George Bent went to Mexico and there married a Mexican girl, by whom he had two children, a son and a daughter. The son, Robert, went to school in St. Louis. He died at Dodge City, Kan., in 1875. George Bent was a great friend of Frank P. Blair, whom he appointed guardian for his children. He died at the fort about 1848 of consumption, and was buried near his brother Robert in the graveyard which lay a short distance northeast of the northeast bastion of the fort. The old tailor, a Frenchman, afterward planted cactus over George Bent’s grave to protect it from the wolves and coyotes. Their remains were later removed to St. Louis.

After the death of Charles Bent, in 1847, William Bent continued his work. Perhaps St. Vrain may have remained a partner for a time. Fitzpatrick speaks of “Messrs. Bent and St. Vrain’s post” in 1850. Bent was an active man and interested in many other projects besides the fort and trade with the Indians. He bought sheep and mules in New Mexico and drove them across the plains to the Missouri market. In the forties, in company with several other men, he secured a large land grant from the Mexican government in the Arkansas valley above the fort and attempted to found a colony there. Mexican settlers were established on the lands. The colonists were inert, the Indians were hostile, and from these and other causes the project proved a failure. In 1847 William Bent and St. Vrain drove a large herd of Mexican cattle to the Arkansas and wintered them in the valley near the fort, thus making the first step toward establishing the cattle industry, which many years later so flourished on the plains.

Besides his lands near the fort, Bent had a fine farm at Westport (now Kansas City), in Missouri, and a ranch south of the Arkansas in the Mexican territory. In 1846 he guided Colonel Price’s Missouri regiment across the plains to New Mexico, and was so popular among the volunteer officers that they gave him the brevet of colonel, a title which stuck to him until the day of his death.