The measures of 1850 proved anything but the "finality" upon slavery discussion which both parties, the Whigs as loudly as the Democrats, promised and insisted that they should be. Elated by its victory in 1850, and also by that of 1852, when the anti-slavery sentiment of northern Whigs drove so many of their old southern allies to vote for Pierce, giving him his triumphant election, the slavocracy in 1854 proceeded in its work of suicide to undo the sacred Missouri Compromise of 1820. Douglas, the ablest northern Democrat, led in this, succeeding, as official pacificator between North and South, somewhat to the office of Clay, who had died June 29, 1852. The aim of most who were with him was to make Kansas-Nebraska slave soil, but we may believe that Douglas himself cherished the hope and conviction that freedom was its destiny.

This rich country west and northwest of Missouri, consecrated to freedom by the Missouri Compromise, had been slowly filling with civilized men. It did not promise to be a profitable field for slavery, nor would economic considerations ever have originated a slavery question concerning it. But politically its character as slave or free was of the utmost consequence to the South, where the resolution gradually arose either to secure it for the peculiar institution or else prevent its organization even as a Territory. A motion for such organization had been unsuccessfully made about 1843, and it was repeated, equally without effect, each session for ten years. None of these motions had contained any hint that slavery could possibly find place in the proposed Territory. The bill of December 15, 1853, like its predecessors, had as first drawn no reference whatever to slavery, but when it returned from the committee on Territories, of which Douglas was chairman, the report, not explicitly, indeed, made the assumption, unheard of before, that Kansas-Nebraska stood in the same relation to slavery in which Utah and New Mexico had stood in 1850; and that the compromise of that year, in leaving the question of slavery to the States to be formed from these Territories, had already set aside the agreement of 1820. These assumptions were totally false. The act of 1850 gave Utah and New Mexico no power as Territories over the debatable institution, and contained not the slightest suggestion of any rule in the matter for territories in general.

But the hint was taken, and on January 16th notice given of intention to move an out-and-out abrogation of the Missouri Compromise. Such abrogation was at once incorporated in the Kansas-Nebraska bill reported by Douglas, January 23, 1854. This separated Kansas from Nebraska, and the subsequent struggle raged in reference to Kansas alone. The bill erroneously declared it established by the acts of 1850 that "all questions as to slavery in the Territories," no less than in the States which should grow out of them, were to be left to the residents, subject to appeal to the United States courts. It passed both houses by good majorities and was signed by President Pierce May 30th. Its animus appeared from the loss in the Senate of an amendment, moved by S. P. Chase, of Ohio, allowing the Territory to prohibit slavery.

Franklin Pierce. From a painting by Healy, in 1852 Courtesy of Wikimedia

Thus was first voiced by a public authority Judge Douglas's new and taking heresy of "squatter sovereignty," that Congress, though possessing by Article IV., Section iii., Clause 2 of the Constitution, general authority over the Territories, is not permitted to touch slavery there, but must leave it for each territorial populace "to vote up or vote down." At the South this doctrine of Douglas's was dubbed "nonintervention," and its real aim to secure Kansas a pro-slavery character avowed. It was consequently popular there as useful toward the repeal, although repudiated the instant its working bade fair to render Kansas free.

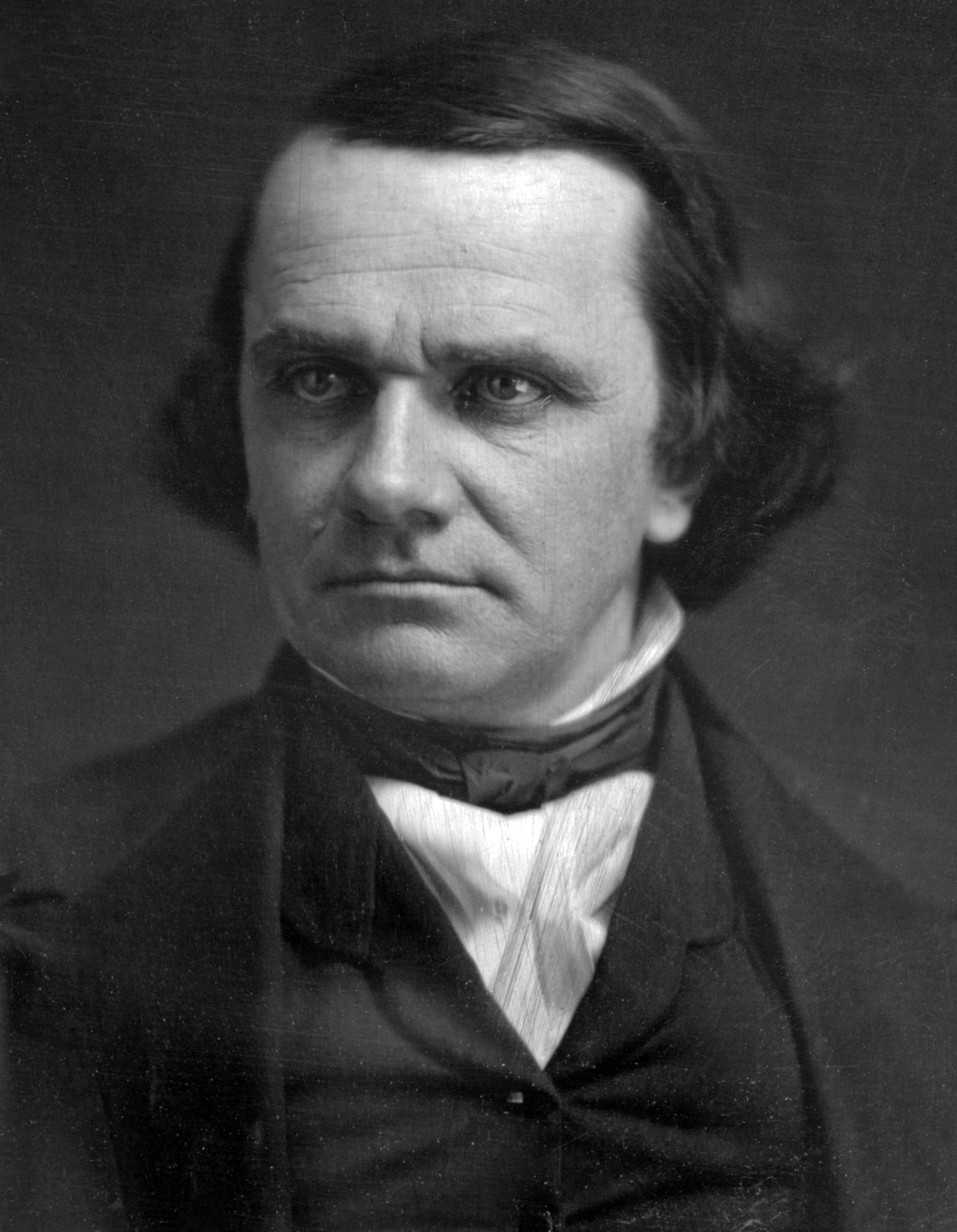

Stephen A. Douglas Courtesy of Wikimedia

1855

This was soon the prospect. Organizations had been formed to aid anti-slavery emigrants from the northern States to Kansas. The first was the Kansas Aid Society, another a Massachusetts corporation entitled the New England Emigrant Aid Society. There were others still. Kansas began to fill up with settlers of strong northern sympathies. They were in real minority at the congressional election of November, 1854, and in apparent minority at the territorial election the next March. The vote against them on the last occasion, however, was largely deposited by Missourians who came across the border on election day, voted, and returned. This was demonstrated by the fact that there were but 2,905 legal voters in the Territory at the time, while 5,427 votes were cast for the pro-slavery candidates alone. These early successes gave the pro-slavery party and government in Kansas great vantage in the subsequent congressional contest. The first Legislature convened at Pawnee, July 2, 1855, enacted the slave laws of Missouri, and ordered that for two years all state officers should be appointed by legislative authority, and no man vote in the Territory who would not swear to support the fugitive slave law.

The free-state settlers, now a majority, ignored this Legislature and its acts, and at once set to work to secure Kansas admission to the Union as a State without slavery. The Topeka convention, October 23, 1855, formed the Topeka constitution, which was adopted December 14th, only forty-six votes being polled against it. This showed that pro-slavery men abstained from voting. January 15, 1856, an election was held under this constitution for state officers, a state legislature, and a representative in Congress. The House agreed, July 3d, by one majority, to admit Kansas with the Topeka constitution, but the Senate refused. The Topeka Legislature assembled July 4th, but was dispersed by United States troops.

1856-1857

This was done under command from Washington. President Pierce, backed by the Senate with its steady pro-slavery majority, was resolved at all hazards to recognize the pro-slavery authorities of Kansas and no other, and, as it seemed, to force it to become a slave State; but fortunately the House had an anti-slavery majority which prevented this. The friends of freedom in Kansas had also on their side the history that was all this time making in Kansas itself. During the summer of 1856 that Territory was a theatre of constant war. Men were murdered, towns sacked. Both sides were guilty of violence, but the free-state party confessedly much the less so, having far the better cause. Nearly all admitted that this party was in the majority. Even the governors, all Democrats, appointed by Pierce, acknowledged this, some of them, to all appearance, being removed as a punishment for the admission. Governor Geary, in office from September, 1856, to March, 1857, and Governor Walker, in office from May, 1857, were just and able men, and their decisions, in most things favorable to the free-state cause, had much weight with the country.

Walker's influence in the Territory led the free-state men to take part in the territorial election of October, 1857, where they were entirely triumphant. But the old, pro-slavery Legislature had called a constitutional convention, which met at Lecompton, September, 1857, and passed the Lecompton constitution. This constitution sanctioned slavery and provided against its own submission to popular vote. It ordained that only its provision in favor of slavery should be so submitted. This pro-slavery clause was adopted, but only because the free-state men would not vote. The Topeka Legislature submitted the whole constitution to popular vote, when it was overwhelmingly rejected. The President and Senate, however, urged statehood under the Lecompton constitution, although popular votes in Kansas twice more, April, 1858, and March, 1859, had adopted constitutions prohibiting slavery, the latter being that of Wyandotte. But the House still stood firm. Kansas was not admitted to the Union till January 29, 1861, when her chief foes in the United States Senate had seceded from the Union. She came in with the Wyandotte constitution and hence as a free State.

It was during the debate upon Kansas affairs in 1856 that Preston S. Brooks, a member of the House from South Carolina, made his cowardly attack upon Charles Sumner. Sumner had delivered a powerful speech upon the crime against Kansas, worded and delivered, naturally but unfortunately, with some asperity. In this speech he animadverted severely upon South Carolina and upon Senator Butler from that State. This gave offence to Brooks, a relative of Butler, and coming into the Senate Chamber while Sumner was busy writing at his desk, he fell upon him with a heavy cane, inflicting injuries from which Sumner never recovered, and which for four years unfitted him for his senatorial duties. Sumner's colleague, Henry Wilson, in an address to the Senate, characterized the assault as it deserved. He was challenged by Brooks, but refused to fight on the ground that duelling was part of the barbarism which Brooks had shown in caning Sumner. Anson Burlingame, representative from Massachusetts, who had publicly denounced the caning, was challenged by Brooks and accepted the challenge, but, as he named Canada for the place of meeting, Brooks declined to fight him for the ostensible reason that the state of feeling in the North would endanger his life upon the journey. A vote to expel Brooks had a majority in the House, though not the necessary two-thirds. He resigned, but was at once re-elected by his South Carolina constituency.

Charles Sumner. Courtesy of Wikimedia

While the fierce Kansas controversy had been raging, the South had grown cold toward the Douglas doctrine of popular sovereignty, and had gradually adopted another view based upon Calhoun's teachings. This was to the effect that Congress, not under Article IV., section iii., clause 2, but merely as the agent of national sovereignty, rightfully legislates for the Territories in all things, yet, in order to carry out the constitutional equality of the States in the Territories, is obliged to treat slaves found there precisely like any other property. If one citizen wishes to hold slaves, all the rest opposing, the general Government must support him. It is obvious how antagonistic this thought was to that of Douglas, since, according to the latter, a majority of the inhabitants in a Territory could elect to exclude slavery as well as to establish it.

The new southern or Calhoun theory assumed startling significance for the Nation when, in 1857, it was proclaimed in the Dred Scott decision of the United States Supreme Court as part of the innermost life of our Constitution. Dred Scott was a slave of an army officer, who had taken him from Missouri first into Illinois, a free State, then into Wisconsin, covered by the Missouri Compromise, then back into Missouri. Here the slave learned that by decisions of the Missouri courts his life outside of Missouri constituted him free, and in 1848, having been whipped by his master, he prosecuted him for assault. The decision was in his favor, but was reversed when appeal was taken to the Missouri Supreme Court. Dred Scott was now sold to one Sandford, of New York. Him also he prosecuted for assault, but as he and Sandford belonged to different States this suit went to the United States Circuit Court. Sandford pleaded that this lacked jurisdiction, as the plaintiff was not a citizen of Missouri but a slave.

It was this last issue which made the case immortal. The Circuit Court having decided in the defendant's favor, the plaintiff took an appeal to the Supreme Court. Here the verdict was against the citizenship of the negro, and therefore against the jurisdiction of the court below. The upper court did not stop with this simple dictum, hard and dubious as it was, but proceeded to lay down as law an astounding course of pro-slavery reasoning. In this it confined the ordinance of 1787 to the old northwestern territory, declared the Missouri Compromise and all other legislation against slavery in Territories unconstitutional, and the slave character portable not only into all the Territories but into all the States as well, slavery having everywhere all presupposition in its favor and freedom being on the defensive. The denial of Scott's citizenship was based solely upon his African descent, the inevitable implication being that no man of African blood could be an American citizen.

This decision rendered jubilant all friends of slavery, as also the ultra Abolitionists, but correspondingly disheartened the sober friends of human liberty. How, it was asked, is the cause of freedom to be advanced when the supreme law of the land, as interpreted by the highest tribunal existing for that purpose, virtually establishes slavery in New England itself, provided any slave-master wishes to come there with his troop? But anti-slavery men did not despair. Patriots had of course to obey the court till its opinion should be reversed, yet its opinion was at once repudiated as bad law. Men like Sumner, Wilson, Chase, Giddings, Seward, and Lincoln, appealing to both the history and the letter of the Constitution, and to the course of legislation and of judicial decisions on slavery even in the slave States, had been elaborating and demonstrating the counter theory, under which our fundamental law appeared as anything but a "covenant with hell."

The pith of this counter theory was that slaves were property not by moral, natural, or common law, but only by state law, that hence freedom, not slavery, was the heart and universal presupposition of our government, and that slavery, not freedom, was bound to show reasons for its existence anywhere. This being so, while Calhoun and Taney were right as against Douglas in ascribing to Congress all power over the Territories, it was as impossible to find slaves in any United States Territory as to find a king there. Slaves taken into Territories therefore became free. Slaves taken into any free State became free. Slaves carried from a slave State on to the high seas became free. Even the fugitive slave clause of the Constitution must be applied in the way least favorable to slavery.

On the other hand Douglas was right in his view that citizens and not States were the partners in the Territories. As to the assertion of incompatibility between citizenship and African blood, it would not stand historical examination a moment. If it was true that the framers of the Constitution did not consciously include colored persons in the "ourselves and our posterity" for whom they purposed the "Blessings of Liberty," neither did they consciously exclude, as is clear from the fact that nearly everyone of them expected blacks some time to be free.

Source: History of the United States, Volume 3 (of 6), by E. Benjamin Andrews, Downloadable at The Project Gutenberg Website.