There was a County Seat war between the towns of Cimarron and Ingalls, and it was in the final phases of that involvement the historian first hears of Mr. Masterson’s brother Jim. Those differences between Cimarron and Ingalls carried interesting features. Not a least of these was the death of Mr. Prather at Mr. Tighlman’s positive hands. The latter exact personage was a citizen of Dodge. Being, however, one who resented narrowisms and to whom any “pent up Utica” was as the thing unbearable, Mr. Tighlman permitted himself an interest in that Gray County contention and, since Cimarron was the natural-born enemy of Dodge, sympathized with Ingalls.

This sentiment on Mr. Tighlman’s part did not meet with the approbation of Mr. Prather, who was a partisan of Cimarron, and when the former appeared at the special election called to settle the question, Mr. Prather—to employ a childish phrase—fell into a profound pout. Mr. Tighlman’s attendance meant nothing beyond a desire to humor his curiosity and flatter that interest which possessed him in favor of an Ingalls success. Mr. Prather, however, in his jealousy for Cimarron, construed it differently and pulled his gun.

Being alert and sensitive, and having had his nerves sharpened by perilous experiences, Mr. Tighlman was instantly aware of this hostile demonstration. As corollary, his own gun left its scabbard coincident with that of Mr. Prather, the result being a weakening of the Cimarron cause by the loss of one. There was no criticism of Mr. Tighlman; for the best belief of folk ascribed a first wrong step to the vanished Mr. Prather. The common feeling was summed up by an onlooker who spoke without prejudice. He said:

“Prather reached for his six-shooter, an’ Billy”—meaning Mr. Tighlman—“beat him to it. That’s all thar was to the fuss.”

The county records were in Cimarron, which had been _de facto_ the County Seat. Ingalls came forth of the election victor, and many held that the taking off of Mr. Prather in its moral effect had much to do with bringing the triumph about. It may have been this thought that suggested to Ingalls the enlistment of Mr. Tighlman’s services when, following the election and in defiance of that ballot decision then and there obtained, Cimarron scoffed at every mention of surrendering the records. Those marks of county authority were the property of Ingalls. What cared Cimarron for that? Cimarron snapped thumb and finger beneath the Ingalls nose! It scorned the election and contemned the result! If Ingalls wanted those records, Cimarron, furbishing up its firearms, would admire to see it get them.

Florence in the fourteenth century retained the military genius of Sir John Hawkwood to its standards and set him to lead its armies in the field. Sir John, as rental for his valour, was given a princely salary while he lived and a marble tomb when he died, which latter monument is still extant, a Florentine exhibit when tourists turn that way. Impressed by the Italian example, Ingalls upon being met by the belligerent obstinacy of Cimarron retained Mr. Tighlman. Would he get those records? Mr. Tighlman would.

Mr. Tighlman possessed a capacity for strategy. He went after the records on Sunday. He argued that, Sunday being a day of rest, the male inhabitants of Cimarron would one and all be in the saloons. Mr. Tighlman deduced rightly on that point, and his rapine of the records was only discovered by chance. A Cimarronian, journeying from one barroom to another, observed him as he threw the last volume into the waggon and sounded an alarm.

Within two minutes thereafter, Mr. Tighlman was shot at five hundred times. And yet he got away and took the records with him. His only injury was received when, a shot having killed a dog at his very feet, he fell over the dog and broke his leg. For all that, he dragged himself aboard the waggon and escaped.

Mr. Tighlman covered his retreat with a shotgun. As a bloodless method of engaging the local faculties, he opened right and left with buckshot on the large front windows that fenced the street. There was a prodigious breaking of glass, and the clatter thereof carried Cimarron almost to a stampede. As showing the blind hurry of the inhabitants, Mr. Tighlman said that he saw one gentleman miss his footing and fall, and before he could even think of getting up eight of his fellow townsmen fell on top of him. It was through such stirring scenes that Mr. Tighlman made his exit, and Jim gained mention because he drove the waggon. The foregoing has nothing at all to do with what follows, and is thrown in only because it may serve as an introduction to Jim.

At what might be called the true beginning of this sketch, Mr. Masterson was located in Tucson, nursing an interest in mines. He had been absent from Dodge divers years. In the interim he had made but a single trip to Dodge, and that a flying one. His brother Jim was temporarily in Camp Supply at the time, two hundred miles to the south, and he missed him. This, however, did not disturb Mr. Masterson, who was in Dodge for the commercial restoration of Mr. Short.

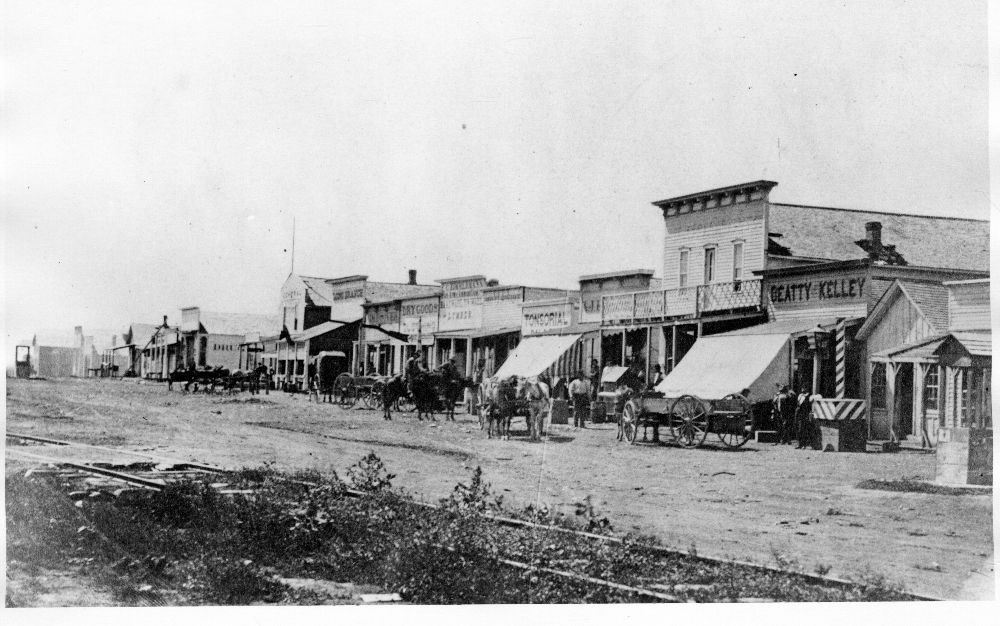

During those years of Mr. Masterson’s absence, the hungry tooth of time had left its marks. Mr. Kelly was dead, Mr. Tighlman was in New Mexico, Mr. Trask had drifted to Montana, Cimarron Bill was in Utah, while Mr. Wright was in Topeka, a member of the Legislature. Of those who had been close to Mr. Masterson only Mr. Short remained.

The others—who if not enemies were but unfriends—had had better luck. Mr. Peacock still ran the Dance Hall, while Mr. Webster kept the Alamo as in days of yore, and maintained under the leadership of Mr. Updegraffe a numerous following.

Even in the time of Mr. Masterson there had been soreness between Mr. Webster and Mr. Short. The Long Branch was garnering a harvest beyond any that lent itself to the reaping hook of the Alamo, and this did not sit easily with Mr. Webster. To be sure, Mr. Short’s success in its causes was easily understood. His deal boxes, like Cæsar’s wife, were above reproach. Folk were never quite sure about the Alamo’s. Also the radical temper of Mr. Short despised a limit. One might pile his stake as tall as he pleased, Mr. Short would turn for it. In the words of an admirer:

“He’d let you play ’em higher’n a cat’s back!” This was not the liberal case with Mr. Webster, who failed of the monetary courage of Mr. Short.

In the carelessness of local politics Mr. Webster became Mayor of Dodge, and he at once took advantage of his power and his elevation to exile Mr. Short. With the latter out of town, the Alamo would fatten and the Long Branch fade.

Being exiled, Mr. Short, following a usual course, hunted up Mr. Masterson, and told his wrongs. Ever and always Mr. Short’s friend, the latter began a roundup of the clan. The old Scotch Chiefs burned a cross and sent it about; Mr. Masterson sent messages and burned the wires.

From East and West and North and South, the loyal tribesmen dropped grimly into Dodge. There was Cimarron Bill and Wyatt Earp and Doc Holiday and Ben Thompson and Henry Brown and Charlie Bassett and Shotgun Collins and Shoot-your-eye-out Jack and many another stark fighting man. When these had assembled, Mr. Masterson and Mr. Short appeared, and the former took command.

There was no trouble; Mr. Webster turned the color of ashes, and Mr. Short resumed his place in trade. Mr. Webster did not like Mr. Masterson any better for this work, although the latter, in adjusting affairs, stretched a point and went excessively out of his way to keep Mr. Webster from being killed. Mr. Masterson said he wasn’t worth it. Mr. Short said he was; but yielded the point in compliment to Mr. Masterson.

When Mr. Short had been restored to the commercial niche that of right was his, Mr. Masterson shook the dust of Dodge from his moccasins, as he imagined for the final time. Nor was he sorry. His friends were gone; and the Dodge he had known and loved and defended had passed away.

In the wake of Mr. Masterson’s departure, Mr. Webster saw, in the hard, gray glance of Mr. Short, that which alarmed his blood. Being wise in a way, he nodded prudently to one who, upon the hint, proffered a romantic figure, and bought out Mr. Short. The latter went to Texas, while Mr. Webster again began to sleep o’ night. With the going of Mr. Short, Jim, for any on whom he might rely, was left alone in Dodge.

That was the situation when one Tucson evening in the Oriental, Mr. Masterson was handed a telegram. He had been hearing evil news all day about his mines, and thinking this a further bad installment tore open the envelope with only a listless interest. What he read stiffened him. The message said:

“Updegraffe and Peacock are going to kill Jim. Come at once. —A.”

With the stop at Deming and a sand-storm raging near Raton, Mr. Masterson was thirty hours reaching Dodge. They were hours without sleep. The imagination of Mr. Masterson raced ahead to Dodge, and drew him pictures. At Albuquerque he feared Jim was already dead; at Las Vegas he entertained no doubt; at Trinidad he knew it was so.

“It’ll be with Jim as it was with Ed,” sighed Mr. Masterson. “I’ll come too late.”

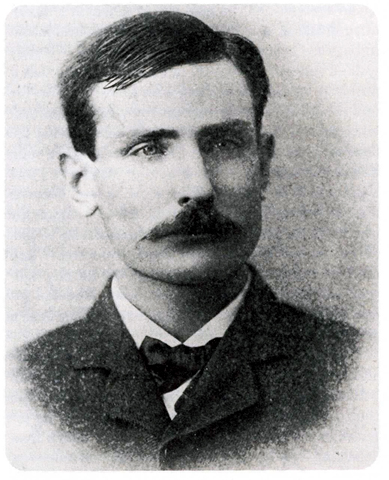

What increased the depression of Mr. Masterson was the raw newness and the youth of Jim. The threatened one was gifted, too, with the recklessness that had betrayed Marshal Ed. This, with his inexperience, only made him the surer victim.

As against this there would arise to Mr. Masterson the hopeless thought of Mr. Updegraffe—as coldly game as any who ever spread his blankets in Dodge! There was none more formidable! Cautious, resolute, without fear as without scruple, it called for the best name on the list when one talked of matching Mr. Updegraffe!

Mr. Peacock was not so dangerous. Still, even he might be expected to shoot an enemy who was looking the other way and thinking on something else. At the least he made a second gun to add to Mr. Updegraffe’s, and with that invincible one for a side partner and only a boy to face, Mr. Peacock must be counted. These were the sorrowful reflections of Mr. Masterson when the conductor passed through, crying:

“Dodge the next stop! Twenty minutes for lunch!”

Whether it were the work of the mysterious “A” who summoned Mr. Masterson, or of someone other than that concealed individual, word had been furnished to Mr. Peacock and Mr. Updegraffe of Mr. Masterson’s coming. There the pair stood waiting in the center of the grass-green plaza of the town.

Mr. Masterson saw them as he stepped from the train; he never saw anyone else. This genius for concentration is a mark of the born gun-player. Mr. Masterson did not parley. His brother had been slain, and here before him were his destroyers. He could feel the revenge-hunger seize him! Making straight for the waiting ones he called:

“You murderers might better begin to fight right now!”

Mr. Updegraffe, with all the coolness of ice, fired point-blank at Mr. Masterson. The shot was two inches wide, and buried itself in a Pullman. At this, certain tourists who had filled the windows with their eager faces, crept beneath the seats.

Mr. Masterson, ignoring Mr. Peacock and honoring Mr. Updegraffe as the element perilous, opened on the latter. The bullet drove before it a piece of rib, and sent the splinter of bone through Mr. Updegraffe’s lungs. The death-blindness upon him, and never a notion of what he was about, he slowly walked a pace or two, and fell dead.

As Mr. Updegraffe went down, Mr. Peacock, who had not fired a shot, took refuge behind a little building that stood in the plaza and was both calaboose and Court House. This discreet disposition of himself by Mr. Peacock was doubtless allowable. None the less it smelled of an unspeakable meanness, impossible to any Bayard of the guns. Thus to take cover is the caste-mark of a mongrel.

So contemptible did this move for safety seem to Mr. Masterson that he would have walked away, leaving Mr. Peacock to enjoy his ignoble security. Mr. Peacock, however, inched his desperate nose around the corner and fired on Mr. Masterson. The bullet broke a third-story window one hundred yards away.

Mr. Masterson’s rancorous interest was rearoused in Mr. Peacock by these tactics. When that gentleman again protruded his nose, Mr. Masterson shot twice at that feature like the ticking of a clock. The lead guttered the side of the building within an inch of the target. Mr. Masterson charged Mr. Peacock, who thereupon took to his heels, and escaped into Gallon’s, which hostelry lay open in his rear.

Mr. Masterson would have followed, but it was here that Mr. Webster, all a-tremble, ran up with a shotgun. At this Mr. Masterson’s eyes shifted viciously to Mr. Webster. That the latter was shaking as with an ague did not lessen Mr. Masterson’s interest in him. Mr. Webster saw that he had attracted the whole of Mr. Masterson’s attention, and was in no wise reassured.

“What are you going to do with that shotgun, Web?” asked Mr. Masterson, tones low and steady but with a deadly focus on Mr. Webster.

“Well,” stammered Mr. Webster, “I’m Mayor, Bat, an’ this shootin’ ’s got to stop.”

“I’ve been reckoned a judge,” returned Mr. Masterson, coming closer to Mr. Webster, watching him the while with constant and forbidding eye; “I’ve been reckoned a judge, and I should say it had stopped unless you begin it again.”

“I shan’t begin it!” hastily asserted Mr. Webster.

“Then let me hold your shotgun,” returned Mr. Masterson, voice iron and syrup. “It doesn’t become your office.”

And Mr. Webster gave Mr. Masterson his gun.

What Mr. Masterson next beheld was as though he saw a ghost. There across the plaza came Jim. Mr. Masterson stared.

“Aren’t you dead?” he whispered. “Dead?” echoed Jim, in wide surprise. “I was asleep over in the Wright House until your guns woke me up!”

Mr. Masterson never understood; Jim never understood; Dodge never understood! Not a soul came forward as the “A” of that message; and the telegraph man said he didn’t know!

And yet it was sure that Mr. Updegraffe and Mr. Peacock were in battle array, awaiting Mr. Masterson. Mr. Peacock being guaranteed a peace, came out of Gallon’s and admitted this. He, too, displayed a message signed “A.” The Peacock message was from Tucson. It ran:

“Masterson has just left for Dodge to kill you and Updegraffe. —A.”

The cloud was never lifted. The queries of “Who sent them?” and “Why?” remain to this hour unanswered.

While the puzzle was fresh, and Mr. Peacock’s message was going from hand to hand, together with the one received by Mr. Masterson, the latter—all vigilance and caution—turned to Jim.

“Get your blankets,” was his low command. “The train will be here in an hour, and we’re going West.”

“We’ll have to put you under arrest!” faltered Mr. Webster.

An ominous shadow settled about Mr. Masterson’s mouth. He opened Mr. Webster’s shotgun with militant prudence; there were two shells in it. Without a word he reloaded the empty chambers of his six-shooter. Being organized, he looked at Mr. Webster and shook his head.

“I must take the next train West,” he said. “I haven’t time today to be arrested.”

“Only for voylatin’ an ordinance!” whiningly explained Mr. Webster, who must do something for his honor. “Dodge has become a city since you was here, Bat, an’ the fact is we ought to fine you five dollars for shootin’ inside th’ limits. As for Updegraffe: onder th’ circumstances no one thinks of blamin’ you for downin’ him.”

“City!” mused Mr. Masterson. “Five dollars! If you’ll consider court as held and the fine imposed, I’ll yield to these metropolitan exactions,” and Mr. Masterson snapped a gold-piece towards Mr. Webster. “And now,” concluded Mr. Masterson, pleasantly, tossing the shotgun into the hollow of his arm, “since I see but few familiar faces, Web, I want you to stay close by my side till I leave.”

“Why, shorely!” murmured Mr. Webster, whom the suggestion discouraged.

When the train drew in, Mr. Masterson saw Jim aboard. Taking the shells from the shotgun, he returned the weapon to Mr. Webster.

“They’d be a temptation to you, Web,” said Mr. Masterson, referring to the shells, “and only get you into trouble. Like many another, you’re safest with an empty gun. Adios!”

“Adios!” repeated Mr. Webster, and he watched the train until it died out of sight in the West.